Book of a lifetime: Clarissa by Samuel Richardson

From The Independent archive: Kate Williams is dragged into a volcanic revelation of sadism and human cruelty that shocked everyone, including its author. Male sexuality has never been explored with such courage

No one evokes the feeling of being trapped like an 18th century author. The smallness of the city, the difficulties of transport and communication as compared to now, meant that one obsession, one place, could take over your life. They say that Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones created earthquakes on its publication in 1749 – if so, then Clarissa should have inspired a volcano. It is a novel simmering with anger.

I read much of Clarissa when I was stranded on an endless train journey between the Midlands and Brighton while in my second year at university. It was a steaming summer, the windows were stuck, the air conditioning broken. I hardly noticed. I was utterly absorbed.

It might seem a simple tale – young heiress seized by a rakish man, is imprisoned, raped and dies – but what was for many years the longest novel in the English language (coming in at a million words), it is almost unbearably gripping. The characters are so obsessed with each other that they cannot think of anything else – and they soon drag you into their warped and dangerous world.

Because the novel is written almost entirely in letters, there is no other voice to balance out their observations, no authorial narrator to guide the reader’s conclusions. You are completely on your own, caught in the crazed, terrified imaginations of Robert Lovelace and Clarissa Harlowe.

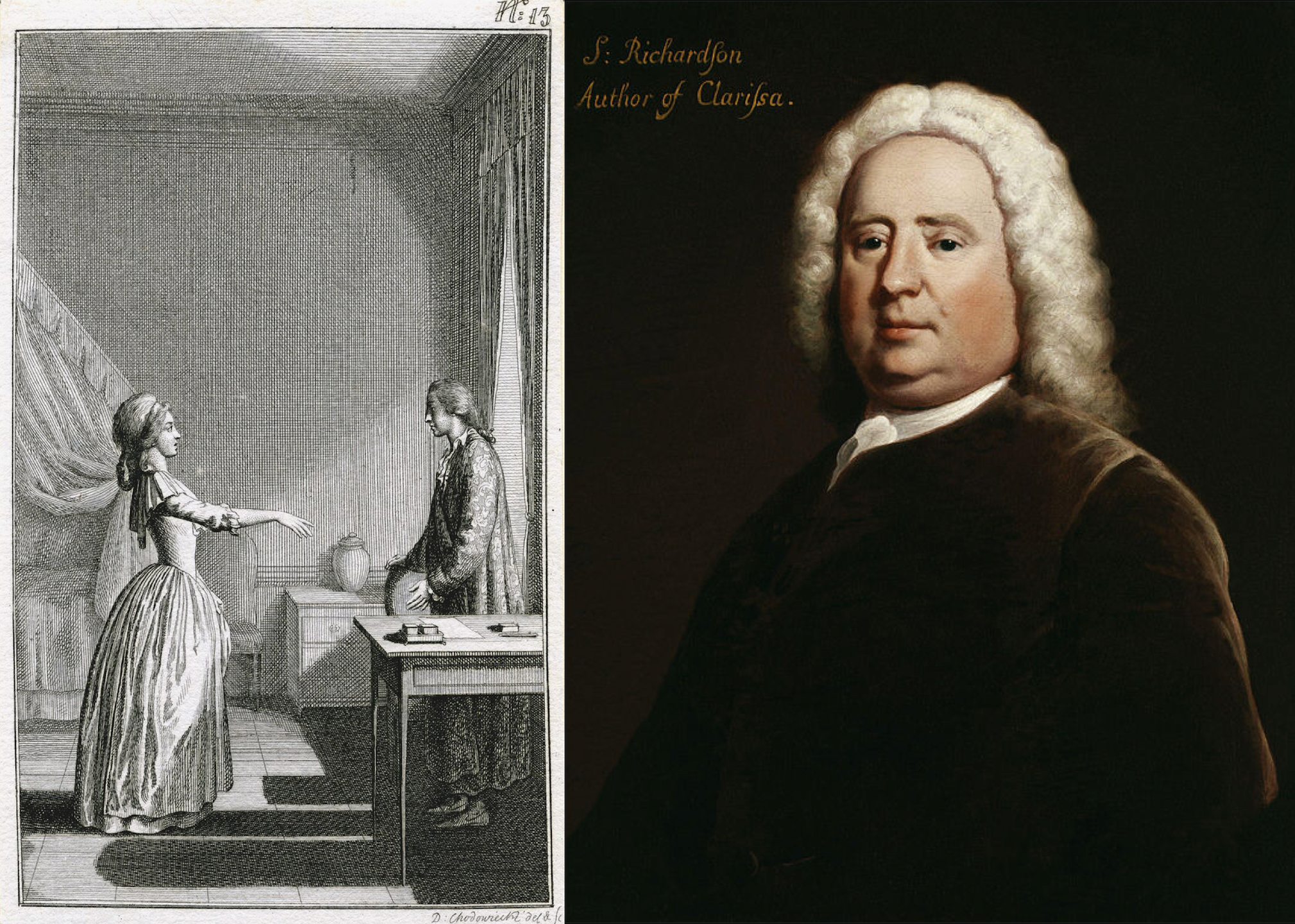

The novel is a paean to the power of the imagination. Samuel Richardson was a plump, self-satisfied, rather pious and happily married businessman from Twickenham. Anyone less likely to produce such a revelation of sadism and human cruelty might be hard to find.

And yet, scribbling away between appointments at his successful London printing house, Richardson explored male sexuality through the awful, compelling voice of Lovelace, and produced the ultimate revelation of how humans are driven to destroy each other.

It’s a terrifying, vicious book. Richardson himself seemed rather surprised by what had come from his pen. Once the book was published, he busied himself informing everyone that he meant it as a text for moral reformation. But to his increasing despair, the public were engrossed by the violence – and many women claimed to be in love with Lovelace.

He began revising the novel and republishing it – producing five editions in all – in an attempt to direct his readers to revile the rake. He failed. In the end, he wrote a further novel in which he tried to exorcise the demons of Clarissa. Sir Charles Grandison is about a hero of the same name, finely upstanding and kind to the ladies of his circle. It is measured, respectable – and utterly dull.

I write on the 19th century now, but my imagination is crafted by the fearful closeness and the cruelty of the 18th-century novel. Once you have read Clarissa, there is no escape from the story. A middle-aged pudding-shaped man from Twickenham began writing in his spare time, and ended up exploring sex and violence with a courage and passion that has never been rivalled.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments