The best art books of 2017

From Antony Gormley to Frida Kahlo, Jean Renoir to Heath Robinson, 2017 has seen a wealth of art books. Michael Glover picks the best of the year

Let’s get the expensive ones out of the way first.

The most visually stunning of this year’s art books is a monograph, a study of a single artist’s work. Hiroshige: Prints and Drawings (Prestel, £99), Matthi Forrer’s survey of that masterful practitioner of images of the floating world who had such an influence upon Monet, Cézanne and so many others, is easily the most eye-catching book of the season – the reproductions could scarcely be more colour-sensitive, and for those with an appetite for additional luxurious fripperies, the book comes in a clamshell-style box, and with Japanese-style binding. It also costs £99. Worth it, though.

The photography that Roger Ballen has been doing in South Africa, his adopted homeland since the 1970s, at last receives the attention it deserves in Ballenesque (Thames and Hudson, £60) a wonderful, career-long survey. Ballen’s images of people are wincingly moving – or, as Emily Dickinson once hauntingly remarked, they’re like a loaded gun.

Antony Gormley (Rizzoli, £100) is Martin Caiger-Smith’s magnificent, magisterial overview of the work of the artist whose body image is probably rusting away at some tideline near you. If Gormley is your man, this is the book for you. I haven’t come across a more sensitive and better informed apologist for the work.

As for books which are more sensitive to issues of the depth of the pocket, Susie Hodge’s Modern Art in Detail (Thames and Hudson, £24.95) is a handsome and useful guide to how great paintings work their magic upon us. How does a painting work? What is behind the creative impulse? She dissects 75 of them in this book, minutely, with a pleasing degree of forensic attention. Having given us a bit of biography, she then cuts each work up into manageable sections, drawing in the kinds of words appropriate to the particular painting under discussion. In the case of a major work by Rothko, for example, the words are these: spirituality, layering, contrasts and movement, tragedy, ecstasy and doom. So it’s in part a technical examination, and in part a free-floating poetic interpretation of a much more personal kind.

Andrew Marr took up the challenge of painting in oils on 2013, after he suffered a stroke. A Short Book about Painting (Quadrille, £15) is a humble, amusing and unpretentious look at issues such as taste, creativity and beauty by a man who brings both his own enthusiasm to the table and his own refreshingly unpretentious insights as a part-time painter.

For a more extended and scholarly look at how painting came into being, how it developed, and all those thorny, issues which are thrown up by the timeless habit of picture-making don’t miss What is Painting? (Thames and Hudson, £24.95) by Julian Bell, a man who both paints and writes exceptionally well.

Julius Bryant’s new book, Designing the V&A: the Museum as Work of Art (Lund Humphries, £35), beautifully dissects the creation of an entire institution devoted to the novel idea of a happy marriage between the arts and the sciences. Every bit of the building is looked at: its staircases, its catering areas, its painting galleries. We see the master plans, and how everything was meant to work as one. The leading arts and designers of the day were encouraged to create an environment which would be the aesthetic equal of what would be displayed in it, each enhancing the other.

Renoir would have been grateful for the thoroughness with which his new biographer Barbara Ehrlich White has peeled away the myths and the lies first disseminated by his son Jean Renoir in an early hagiography of his father. Drawing on hundreds of unpublished letters, Renoir: An Intimate Biography (Thames and Hudson, £24.95) reveals how the poor man fought back for so long against illness, and created an entire fantastical world of overflowing nudes or near-nudes as a form of consolation for his creeping physical decrepitude.

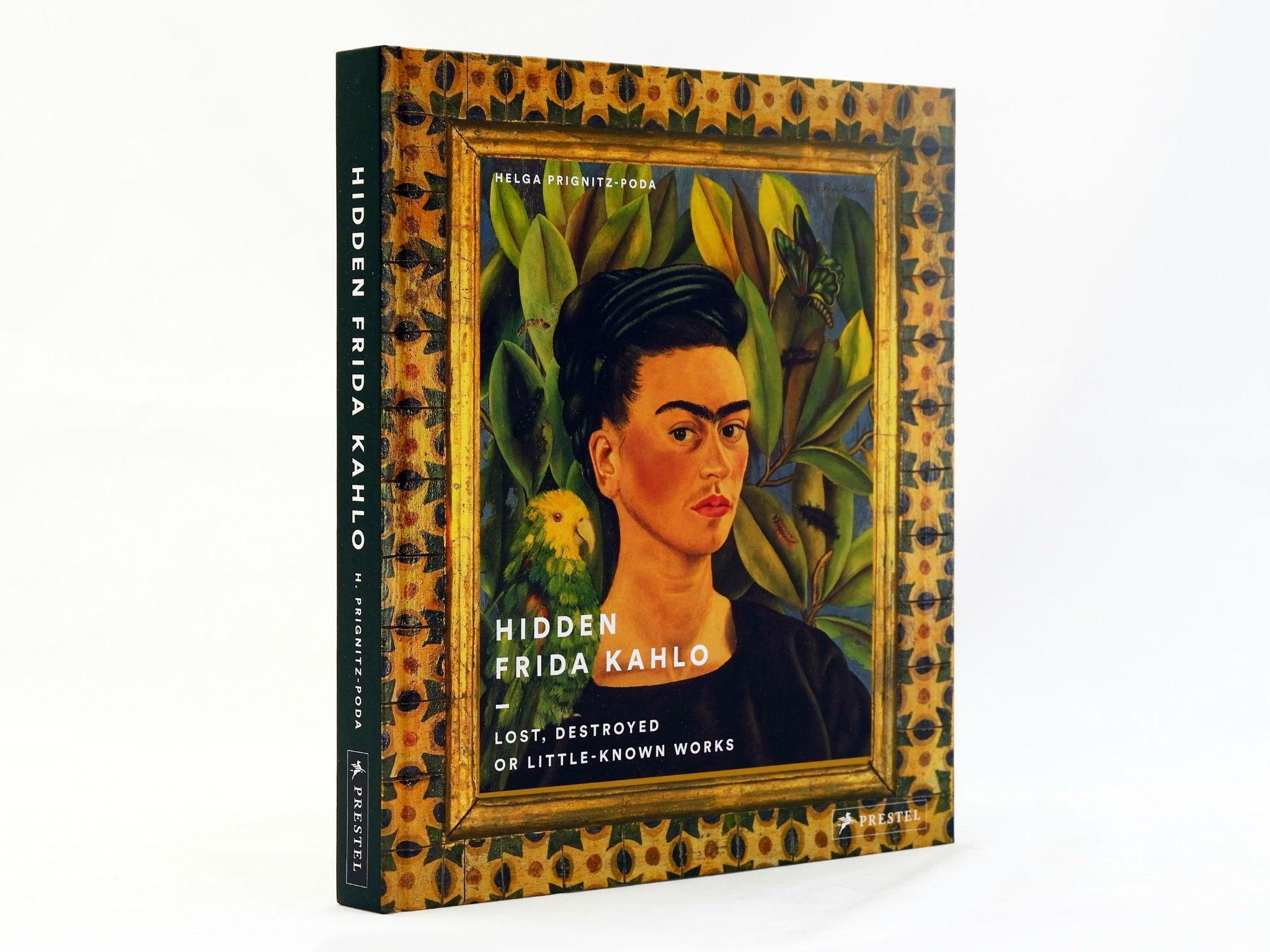

Are you mad about Frida Kahlo? This is your moment. Vanna Vinci has chosen the form of the graphic novel for Frida: The Story of Her Life (Prestel, £19.99). She does it in a dreamily surreal way – the illustrations float and swim around the page. The book pairs well with another excellent book from the same publisher about all those works by Kahlo that went missing or are seldom seen. It’s called Hidden Frida Kahlo: Lost, Destroyed or Little Known Works by Helga Prignitz-Poda (Prestel, £39.99).

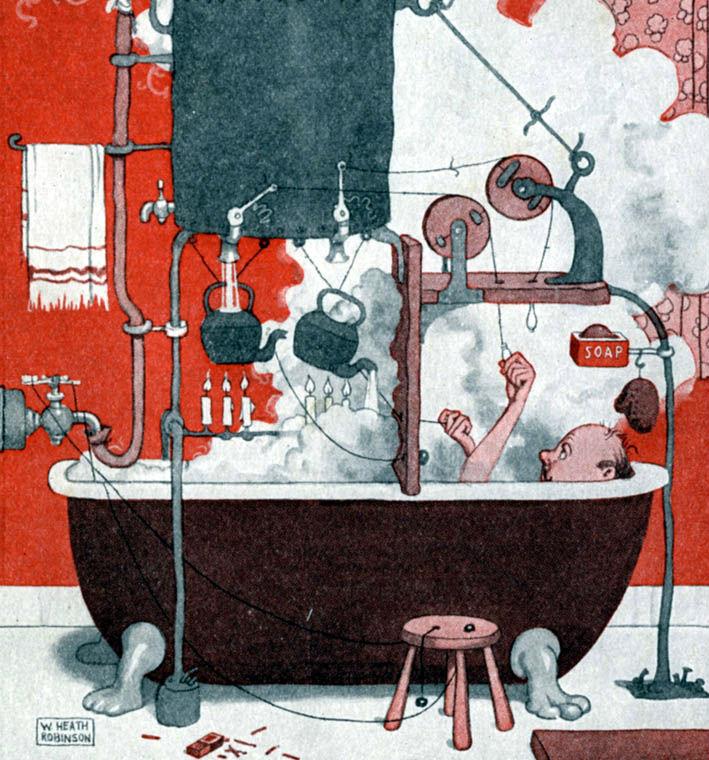

Heath Robinson was the greatest artist of absurd contraptions ever dreamt up by a shock-haired inventor. Now at last we have a tribute worthy of his talents appears in Heath Robinson’s Commercial Art: A Compendium of His Advertising Work (Lund Humphries, £40). The very titles of his often immensely complicated and ingenious drawings are appetite-whetting enough: the whole of the front page of the Daily Mail on 1 October 1921 was taken up by Robinson’s Impression of Toffee Town. It’s been downhill all the way since then. This book’s designed to titillate children of all ages.

New books about Barbara Hepworth are always welcome – she talked almost as well as she sculpted – and this season there are two, and Sophie Bowness, her granddaughter, is responsible for both of them. Barbara Hepworth: the Sculptor in the Studio (Tate, 16.99) is a history and a guided photographic tour of her studio in St Ives. Her Collected Writings and Conversations (Tate, £18.99) brings together lectures, speeches, interviews and much else.

She is always crisp and to the point. What is exactly is Monolith, Barbara? This is how she replied to that question in 1954: ‘MONOLITH should stand elevated in the landscape. The rising forms spring from the bridged, pierced hollow which could be the bridge between the body and the mind seeking comprehension.’ There you have it then. The sculpture in question was conceived as a tribute to her son Paul and his navigator, who were both killed on active service with the RAF in Thailand.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments