Suffragist light sculpture marking women's right to vote battle sets British Parliament aglow

Parliament’s new addition – a six-metre-high light installation – celebrates 150 years since the first petition for women’s votes

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Mary Branson, Parliament’s “artist-in-residence” for women’s suffrage, confesses she didn’t know so much about the women’s rights movement before she began her ambitious piece New Dawn, celebrating 150 years since the first petition for women to vote was presented to the House of Commons.

"I didn't really know very much about the wider movement at all," she says. "I was at school in the Seventies and we had no women’s history at all – what we did have was limited and mostly centered around the suffragettes." Branson had formerly been commissioned to create a tribute to Emily Davison at Epsom Downs racecourse in 2013, and admitted she was a little shocked when she uncovered the true scale of the movement in parliamentary archives.

"No one had really done much research into just how petitions had been filed supporting womens right to vote before – there were 18,000 petitions with around three million signatures. This movement was more than the suffragettes: it was full of ordinary women, men and children, and I wanted New Dawn to honour them."

Indeed, in 1866, long before the suffragette movement, the Women's Suffrage Committee collected 1,500 signatures on a petition for women’s suffrage, the first to formally be presented to the House of Commons by philosopher and MP John Stuart Mill, 150 years to the day of the uneveiling of Branson's work.

Branson set out her research visiting the parliamentary archives and the London Museum, interviewing MPs, suffrage historians and parliamentary experts. "I ended up doing a lot of historical research. There was information missing that I had to make up for – I've sort of been obcessed since I first started the project in 2014."

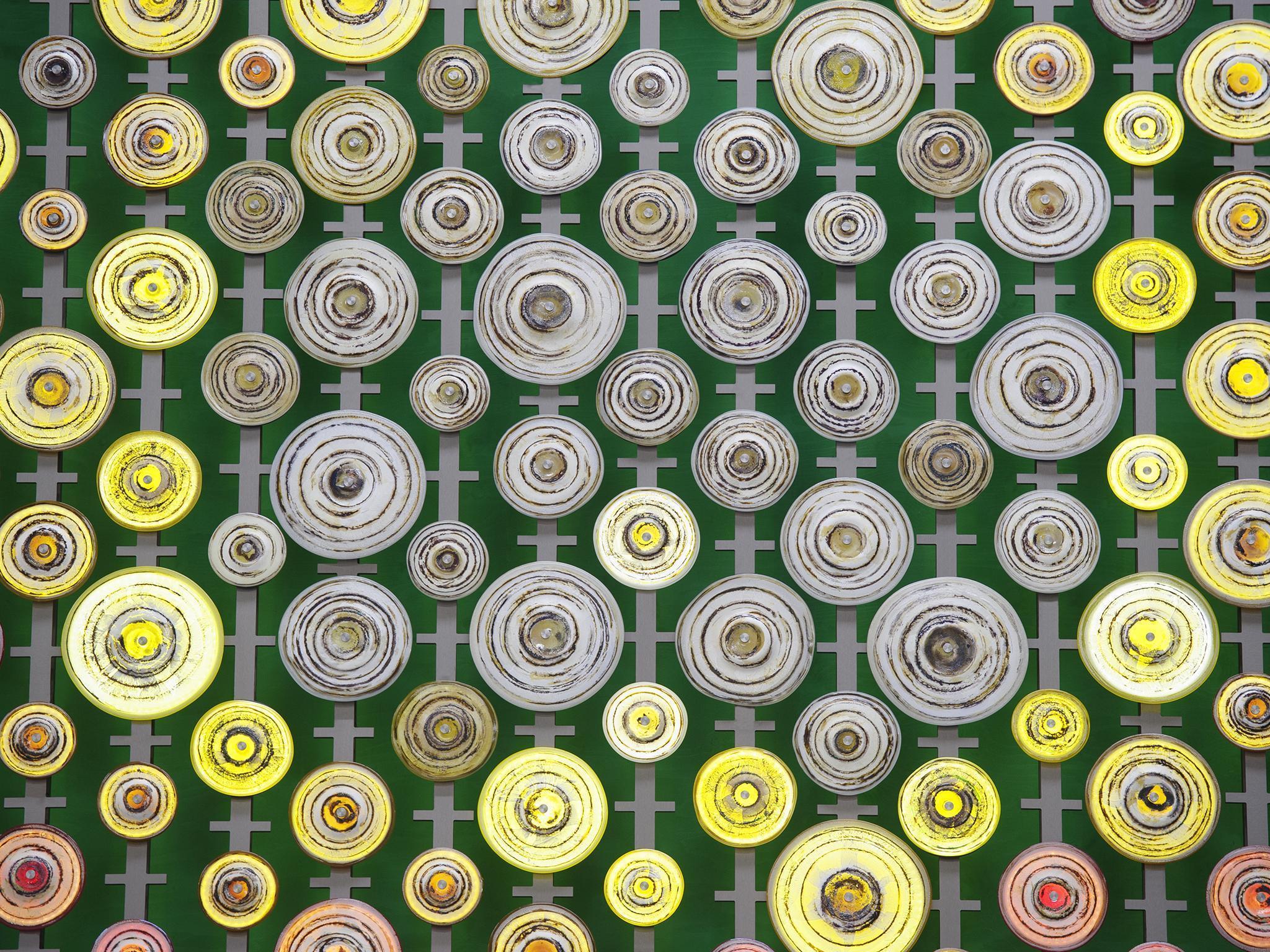

New Dawn now proudly sits above the St Stephens entrance of Westminster Hall, made up 186 individual hand-blown glass scrolls. The scrolls are inspired by the beginnings of Branson's research, visiting the parliamentary archives, looking over at old scrolls from public acts, tagged in colour to indicate who was monarch at the time. "The corridor was so awash with colour," she says. "I continued to return there throughout. A lot of my other research was looking into old seargent arms folders – they don't detail only activists such as Pankhurst, but also women going to Parliament day, after day, risking everything."

Branson changed the colours from representing a monarch to the many organisations that stood up for womens rights: the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies, the Women's Social and Political Union, the Women's Freedom League and the Men's League for Women's Suffrage.

"What I found was that it always boiled down to: what would you be, a sufferagette or an anti-sufferagette? People are controlled by fear."

Branson compares them with modern-day protesters: "These men and women would travel all over the country, they were relentless, and they were risking their jobs, families in the process. We take freedom of speech for granted now, but it was much more of a risk to put your name on a petition than it is now. The bravery astonished me."

"These were ordinary women, who would go to protest and would have food thrown at them, they lost their jobs for writing a name on a petition. I wanted to honour bravery of normal people who stepped up to the plate."

Searching through archives Branson found a number of anecdotes, such as Muriel Matters, whom had attempted to use a hot-air balloon to distribute votes for women pamplets – only to be blown away by the wind "They were inventive" Branson laughs.

And she found letters written on pieces of toilet paper from those incarcerated for demonstrations: "There was one woman whom had been convicted of throwing stones at officers. She wrote a letter to her husband on this piece of loo roll, and she's just so shocked, she can't believe she has been caught. She's so terrified."

Branson attempted to reflect this individual spirit coming together as a collective within New Dawn: "All the disks are individual, imperfect. I wanted to demonstrate how it wasn't simply a gender that achieved the vote, but a a collection of individuals. When women work together they are powerful."

The gravity of the fight for the vote, inspired Branson to create a larger piece, "I saw this dark corner in the St Stephens entrance, and I remember asking one of the guides if anything was meant to be there. I'm a light installation artists and I thought: I'm going to light that." The St Stephens entrance to Westminster holds particular emphasis to women’s history, with a number of demonstrations including those by the suffragettes in October 1908 (in which many demonstrators chained themselves to gates), took place metres from where Branson's artwork now stands.

"I wanted it to be where they once stood. The hall is such a cold, masculine area. It was built by men and for men. I wanted the piece the insert a warm energy."

New Dawn isn't just about what happened during the suffrage period, Branson insists. "That’s why its linked to tide. The fight for equality is constant and comes in waves." The piece is linked to the tide of the Thames. The ebb and flow of the illumination in turn reflects the rising tide of change.

The time frame between "high tide" and "low tide" is representitive of the period of change between the first petition being given to Parliament and the vote being granted for women in 1918. The colours of prominent organisations of each period grow and then fade as time passes – such as the suffragettes who appear in purple just before high tide. Indeed, entering into Westminster Hall toward the St Stephens entrance, the piece appears to be alive.

Of course, comparisons will be drawn between today’s equality movements and those that took place a century ago: “Social media is very exciting to see, and great organisations like No More Page Three, Everyday Sexism and Sisters Uncut doing incredible jobs and doing them in different ways. I want people to look at New Dawn and enjoy it, to think its beautiful. But also to come away and think about it, to think about the fight for equality and what they would have done then – and what they can do now."

‘New Dawn’ is free to visit for the public, tickets are available on visit.parliament.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments