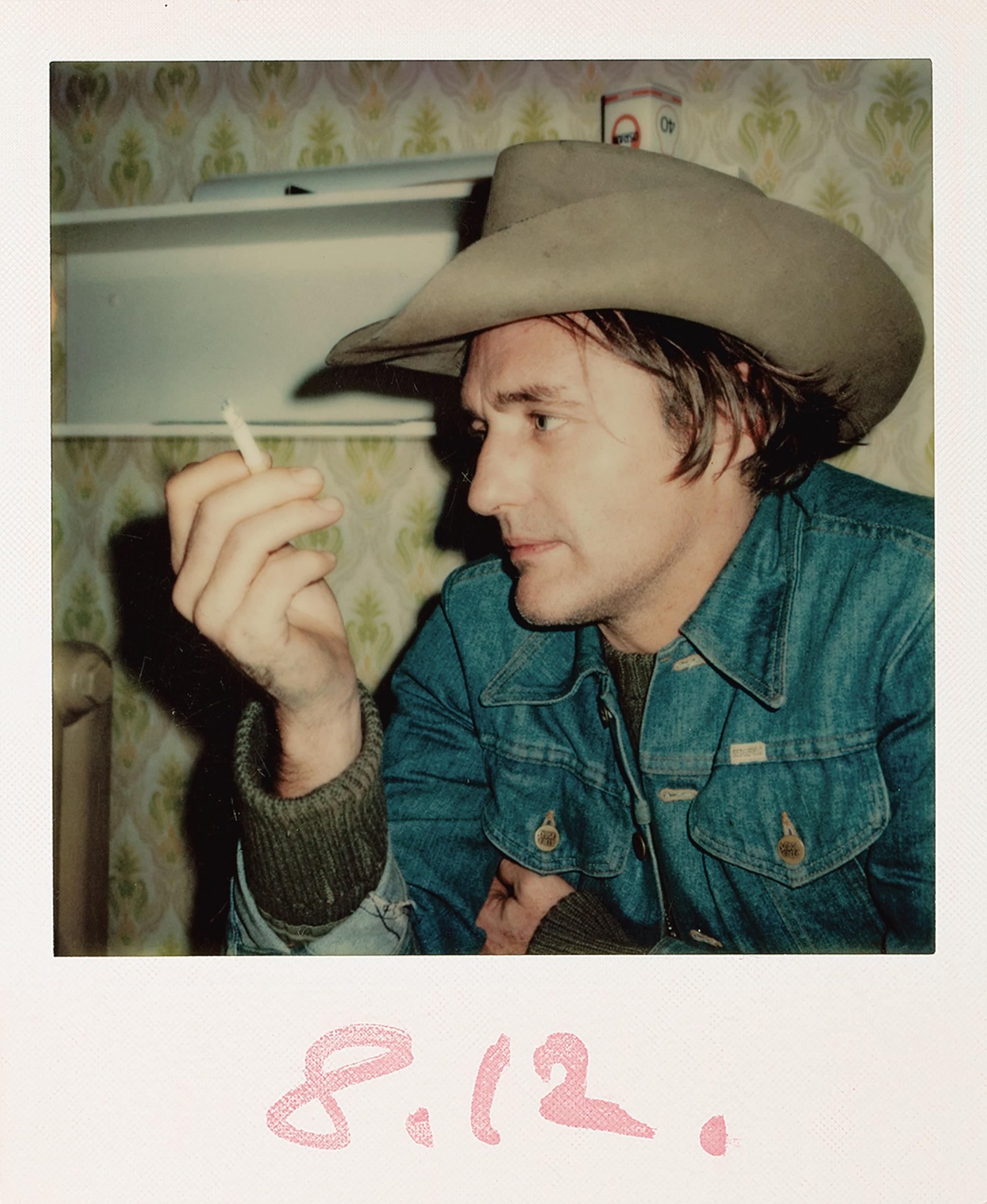

Wim Wenders, Early Works: 1964-1984, Blain/Southern, review: Wenders loves blur because life itself is a blur

C-prints, based on original Polaroids, and black-and-white photographs from the German filmmaker and photographer's archive, include shots while on the locations of his films

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The Wim Wenders experiment in life, ever restless, ever serendipitously globe roaming, is a studiedly impromptu affair. We could define his angle on the world by deploying a series of adjectives which begin with un-: unswanky, unposy, unglossy, unfabricated, unmanipulated, unslick. Photography and filmmaking have gone hand in hand for decades.

His films, at times, seem to consist of a concatenation of individual photographic stills, informed by an intimate relationship with some of his favourite artists – Pina Bausch, Edward Hopper, Andrew Wyeth. Think back to the melancholy poignancy of the closing scene of Paris, Texas, for example, when Travis sits alone in his car, bathed in an eerie pool of green light, having relinquished his son to the child's mother. That visual moment is pure Hopper in its exquisite desolation.

Wenders shifts easily from documentary to feature films, from part fact to part fiction, and when he films he always takes photographs too, sometimes as outtakes, sometimes as a species of note taking, as a way of making real, as a way of registering the importance of the presence of the actors he has worked with or of the landscapes or the cityscapes in which those films are rooted. You could call his love of realism anachronistic. He is an analogue man. The digital world is too slippery. He distrusts a technology which allows for, and even encourages, the dangerous possibility of instantaneous erasure, the buffing up, the removal of the wrinkles, of the past, that urge towards the fakeness of perfection. The world is not an illusory place. Nor is it perfect. It needs to be embraced, grasped at, snatched at, quickly, on the wing, in all its pocky rawness.

He fell in love with Polaroids early, that promise of crisp fleetingness, and this new exhibition shows us some of those early experiments in this curious format. They were discovered quite recently, in cigar boxes, which had served as humidors, preserving them, by happenstance, from perishing. The pictures look so distinctively of themselves now – boxy in format, with a surface which looks and feels thickened, even a touch custardy, with queasy greens and yellows. Wenders loves blur because life itself is a blur, always on the wing, always part seen and part gone, and all the more cherishable for that very reason. Wenders drifts about the world like a windblown seed, from Montana to Iceland, from Algiers to Australia. Scenes can be both panoramic and forensically detail-attentive, simultaneously. Who else has photographed from the summit of Uluru by drawing our attention to the weather-pummelled refuse bin which sits at its centre? He sees how a waterfall can choose to resemble the sweep of a blonde's hair when caught from behind. He registers the absurdity of giving the name EDEN to a gim-crack prefabricated building in Iceland in the shadow of forbidding mountains. He is always shooting from the hip with the most harmless of weaponry.

Until 5 May (blainsouthern.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments