Visible Invisible, Parasol Unit, London

Mind games, lies, deception – all are playfully and thoughtfully explored in this exhibition that sets off a new trend

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.How far exhibitions are creatures of their time is open to debate. Curators are as prone to personal history as they are to art history, the work they favour reflecting both the zeitgeist and their potty training.

Still, a show called Visible Invisible: Against the Security of the Real at London's Parasol Unit does make you wonder if there is something afoot in the world, the artists in it being uniformly concerned with deceit.

Art has always been tied up with deception. When Zeuxis painted grapes so real that birds were said to have come down to peck them, he was lying not once but twice: in trompe-ing the oeil in the first place, and in making up a story about it. (Birds cannot see in metaphor.) Abstraction, the varied squares of Malevich and Mondrian, set out to unshackle art from illusionism or, if you prefer, from lying. All painting sits on a line between Zeuxis and Malevich, between fooling the eye and refusing to do so.

So, what of artists who aim specifically for the mid-point of that line – who make work that flickers back and forth between illusionism and abstraction? In the days of high postmodernism, narrators of novels would stop mid-flow to remind you that they were narrators of novels, that what you were reading was fiction. The work in Visible Invisible does something else. Although pretty well all the artists in the show go in for pastiche, it is not with glib postmodern intent. Pastiche calls for an act of memory, a recognition of the thing pastiched. The best work in Visible Invisible – and it is a very good show full of very good work – offers you half-seen glimpses of things half remembered which prove not to be there when you come to look for them.

Take Katy Moran's Salter's Ridge, in acrylic on canvas and about a foot and a half square. It is intentionally overlookable – small, unframed – and yet its palette is reminiscent of Manet. Stare at the work and you expect to see a picnic on the grass. Except that you don't, because it isn't there: for all their hints at figuration, Moran's brush strokes are just that, sweeps of paint.

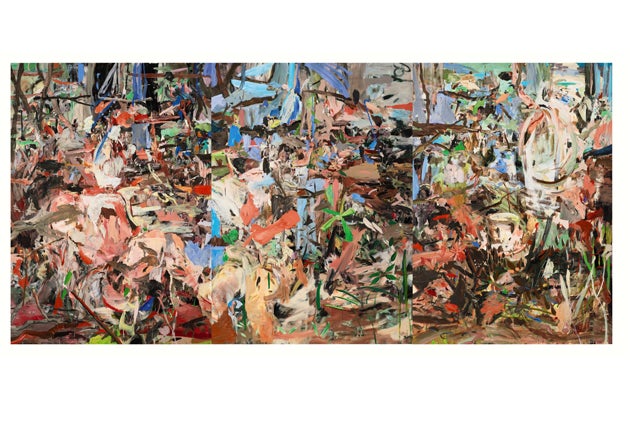

Much better known than Moran, Cecily Brown does the same thing in reverse. Her large triptych, Girl Eating Birds, looks at first to have been made in the heyday of Abstract Expressionism, its mosaic of forms and colours mere mark-making and gesture. In fact, they are more in the way of collage. Woven on the picture's surface are motifs that read as hands with pointing fingers, a human figure, sprigs of greenery, some kind of vessel. The triptych's three canvases run together as if to suggest a continuous narrative that isn't there. As with Moran, Brown plays games with memory, using our memory of looking at art to raise expectations and dash them.

Why? The nearest equivalent I can think of to what Brown and Moran are doing lies in the work of a short-lived movement of the mid-1930s called Objective Abstraction, championed by artists such as Rodrigo Moynihan who would later sign up to the Euston Road School. The aim of Objective Abstract work was to hint at representation the better to be non-representational. Only by allowing the possibility of illusion could an artist show that he was having no truck with it – that his art was about painting paint, not painting bowls of fruit.

In this, Objective Abstraction was modern in an old-fashioned way. The territory it explored had already been mapped by the Impressionists, and playing around with representation meant avoiding the scarier modernity of painters such as Ben Nicholson. Like Moynihan, Brown and Moran and the three other artists in Visible Invisible seem to define themselves against the prevailing modernisms of our day, not by being postmodern and jokey but by opening the Pandora's box of history. Bound up in their work is the story of art and the story of our looking at art: a work such as Salter's Ridge is a kind of Rorschach blot, our reading of it shaped by our own experience.

Perhaps the most surprising thing about the painting in this show (there is also strong work by the octogenarian Swiss sculptor, Hans Josephsohn) is just how painterly it is. For all their games with tradition, Brown and Moran handle their medium with a skill and sureness that buy into the past. Whatever questions they ask about where painting is going, they are certain that it is going somewhere. Objective Abstraction lasted a couple of years before hitting its own cul de sac. Let's hope this new trend lasts longer.

'Visible Invisible' (020-7490 7373), to 7 Feb

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments