Thresholds: works from the British Council collection chosen by Paula Rego, Whitechapel Gallery, London

Many curators and museum makers have tried to make sense of the art of the 20th century, chopping it up into convenient units, herding artists who barely knew each other into groups, telling us that this belongs to that, spinning interminable yarns about this -ism and that -ism. Most of it is journalism.

This exhibition, a selection of 50 paintings, prints and photographs from the British Council's collection chosen by Paula Rego, is a little different from the usual over-regulated show. It is more intimate, more serendipitous, and wholly unprogrammatic. Rego isn't concerned to tell a story about movements at all. What she has been keen to do is to find works which quicken, beguile and amuse her as a seasoned practitioner. She is a painter who delights in storytelling – there is a great deal of open-ended storytelling here. She is a painter who enjoys bringing books alive in unusual ways by illustrating them; David Hockney does the same kind of thing in the selection here of etchings based on Grimm's fairy tales.

Rego is the kind of painter who makes us ask questions when we stand in front of her paintings. Questions such as: what can possibly be the outcome of this confrontation? What can she be thinking at this moment? These are everyday, human questions. She creates fantastic-looking, costumed tableaux in which the childish and the adult get horribly intermingled. For something similar, look at a wonderful, undated painting here by Colin Hayes called The Fifth of November. Three costumed people stand in a perfectly ordinary room. One is extravagantly dressed in a tricorne hat and a pale, ghoulish mask. His female companion has straw for hair and a carrot's nose. Nothing is happening. They are preparing to begin. To do what though? What exactly is happening here?

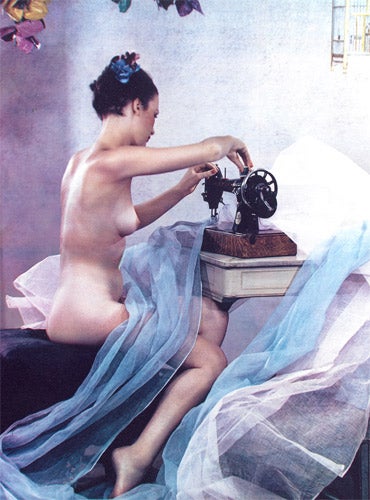

This is a question we ask ourselves again and again in this show, which consists almost entirely of figurative works. Each one seems to be charged with drama of one kind or another, imbued with a mood of slightly anxious expectation, as if ready to be interrogated about its meaning, its purpose. A number of them are by artists known to all of us; Freud, Hockney, Sickert. Others have fallen from view. Look at the marvellous – and marvellously bizarre – early photography of nudes by Madame Yevonde, for example. This forgotten pioneer, born Yevonde Cumbers in good old Streatham, incidentally, deserves an entire exhibition to herself.

But even when the artists are well established, Rego has managed to pull something slightly unusual out of the cupboard. Look at these drawings by Walter Sickert, for example. They bring to mind a grisly series of paintings called The Camden Town Murders. Those paintings were very memorable tonally, the dubious morality of their darkness threatened to engulf us. Rego has managed to find a small group of prints and drawings which cover much the same ground – in one, the threatening male presence, fully clothed, still hovers around the female bed, but these are much lighter and less heavy in tone, and therefore less oppressive in feel. You could even say that they are suggestive of conviviality. The threat of brutality has lifted somewhat.

Generally speaking, the works are all relatively small. We often have to peer quite hard to understand the importance of the details. It is rather as if they are hoarding their secrets. In a wonderful painting by Michael Andrews called Recollection of a Moment in October 1989 – The Tobasnich Burn, Glenartney, a man seems to be slipping down a cliff, arms flung helplessly wide into the path of a raging torrent. It is absolutely terrifying. But you barely notice the figure until you stand very close to it. The painting is so mystifyingly dark that you feel you are peering into a cave's mouth.

To 14 March (020 7522 7878)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments