Revolution: Russian Art 1917-1932, Royal Academy of Arts, London, review: A hugely ambitious show

Focusing on a period of 15 years, just before Stalin’s clampdown in 1932, this exhibition of works includes paintings, photography, sculpture and filmmaking, at a time when Russian art was booming

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.This is a hugely ambitious show with loans obtained from Russia that you will never have seen and many that you will not see again. Planned to coincide with the centenary of the Russian Revolution it covers a period in Russian history where for a brief moment everything seemed possible and continues through the suppression of the avant-garde.

The galleries are arranged thematically, starting with the rise of Lenin followed closely by the advent of Stalin. Along the way we encounter hard physical labour, peasants working the land, the rise of the Russian avant-garde and finally the new Russia. Is it coherent and digestible? No. But it is fascinating.

The curators have chosen to make the installation layered, which is a polite way of saying they have chosen to include everything. With ceramics, photos, posters, advertisements and documents, paintings and films often mounted high above everything. With everyone earnestly listening to headsets to try and decode the difficult history, it is also difficult to physically negotiate.

Setting the scene are several portraits of Lenin. One by Gorgy Rublev, Portrait of Josef Stalin (c.1930) with its bristly moustache and peaked eyes reading a newspaper, seems strangely cartoonish, the large thone-like chair enveloping the leader, making him seem improbably small and powerless. We move immediately into hard labour with a large painting by Ekaterina Zernova, Tomato Paste Factory, looking particularly harsh yet more familiar as a Russian propagandist image.

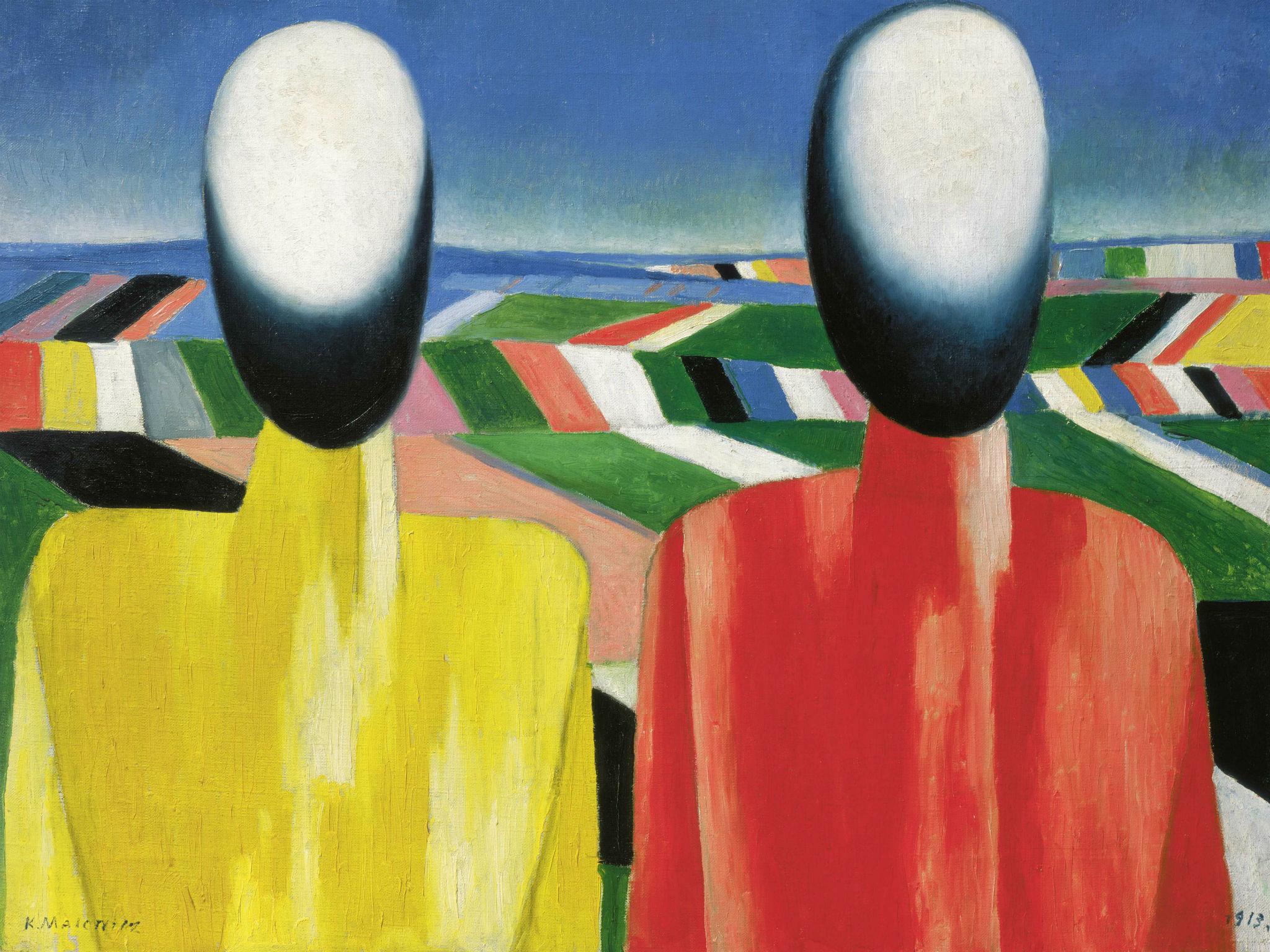

In a section labelled a Brave New World, a room of Malevich reductive paintings as always impresses. It is amazing how saying so little can impart so much information. A recreation of an apartment interior by El Lissitzky nods to the brief flourishing of design, while whirling nearby is a recent recreation of Tatlin’s Letatlin, with strange flying machines twizzles endlessly around.

There is a room of the work of the unknown Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin. No one outside of Russia has heard of him although there have been attempts before to raise his profile. A poetic vision of a peasant’s simple dinner of potatoes, bread and herring, Still Life with a Herring (1918), painted on oil cloth, shimmers, but it is Midday Summer (1917), a painting of the artist’s father’s funeral, that transfixes me. Framed by improbably large apples the perspective is scientifically wrong, but the aura of serenity shines through as the simple cortege moves through the strange landscape. It is as if his father is looking down and is part of this moment. It mirrors the nearby joyous The Promenade by Marc Chagall, in which the young artist proudly whirls his new bride aloft his head like an improbable flag.

We are plunged immediately back into the a transformed Stalinist Russia with paintings of honed athlethic bodies and finally deposited through a strange tunnel to be faced by Arkady Shaikhet’s film of physical training. The film is mesmerising, especially in the light of current revelations about doping in Soviet athletics. At a small cinema nearby one can watch the harrowing work of art critic Nikolai Punin. Portraits from his personal investigation file as a prisoner in 1949 is testimony to the punishment of the artist under a punishing regime.

Leaving an exhibition on the downward swoop of a metaphorical rollercoaster ride, this is the type of ambitious exhibition that pleads for people to become Royal Academy members so that they may come freely again and again. Would it be worth a return visit? Yes – especially at this moment of time if, like me, you are considering the potential effect of the Trump-Putin alliance seriously.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments