Review of 2012: Visual art

The strongest impression left by the year's best shows, such as 'Mondrian/Nicholson: In Parallel' is that less is more

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.

Best show of 2012

I'm going to split this award in two, one British and one foreign, the runaway best show of the year having been in Rotterdam. How could anyone hope to compete with the Boijmans Museum's The Road to Van Eyck, for scholarship or for loveliness of content?

But even in these benighted isles, 2012 was a bumper year for small, clever exhibitions. Which to choose? In March, using just four pictures of card players and five of servant-girls, Taking Time: Chardin's Boy Building a House of Cards at Waddesdon Manor mingled the twin histories of pre-revolutionary French taste and Rothschild collecting. Marvellous. In October came Barbara Hepworth: The Hospital Drawings at the Hepworth Wakefield: a suite of little-known, little-seen, lapidary works, made in fake gesso and two dimensions by Britain's pre-eminent 20th-century woman sculptor. Will anyone who saw it ever think of Hepworth in the same way again? My overall winner, though, has to be Mondrian/ Nicholson: In Parallel at the Courtauld in February – a show which, in 20 works or so, brought to life that moment in the 1930s when Britain was a fleeting part of the European avant-garde, when to be a Britartist meant being engaged, outward looking, modern. Gold-medal curating, and my Show of the Year. From which list we may deduce various things, the first being that, exhibition size-wise at least, more is less and small is beautiful.

Weirdest art fair of 2012

For a decade now, Regent's Park has filled each October with rich people in silly clothes, there to compete with other oddly dressed rich people in buying contemporary art in a tent. I refer, of course, to the Frieze art fair. This year, though, the Jimmy Choo folk were joined by a separate subgroup, filing into another tent discreetly built at the other end of the Park. This was Frieze Masters, a place to buy (gasp!) old art. That might have suggested a dress code of its own – well-cut tweeds and flat shoes, say – if “old” hadn't been ingeniously redefined for the occasion to mean “made somewhere between 5000BC and AD2000”. What to wear if you plan to pick up a piece of Cycladic sculpture and an early Tracey Emin embroidery at the same time? No one seemed quite sure. Fashion-wise, my dears, the result was disaster.

Heaviest show of 2012

Up to mid-August, the apparently unbeatable frontrunner in this class was Gagosian's Henry Moore: Late Large Forms, a title that gave the game away as to the heft of what was on show. By a feat of combined will and low-loaders, the gallery had managed to pry such monsters as Moore's Large Four-Piece Reclining Figure from their plazas and bring them to London. Hurrah! But then, hardly a month later, things went awry for Gagosian: Bronze opened at the Royal Academy. If no single work in this giant matched up to Moore's behemoths in terms of unit size, the exhibition's collective weight – 700-plus objects, all in a notoriously hefty alloy – must have tipped the scales at, ooh, 100 tons? Give or take. Heavy, man. Sorry, Larry.

Patchiest show of 2012

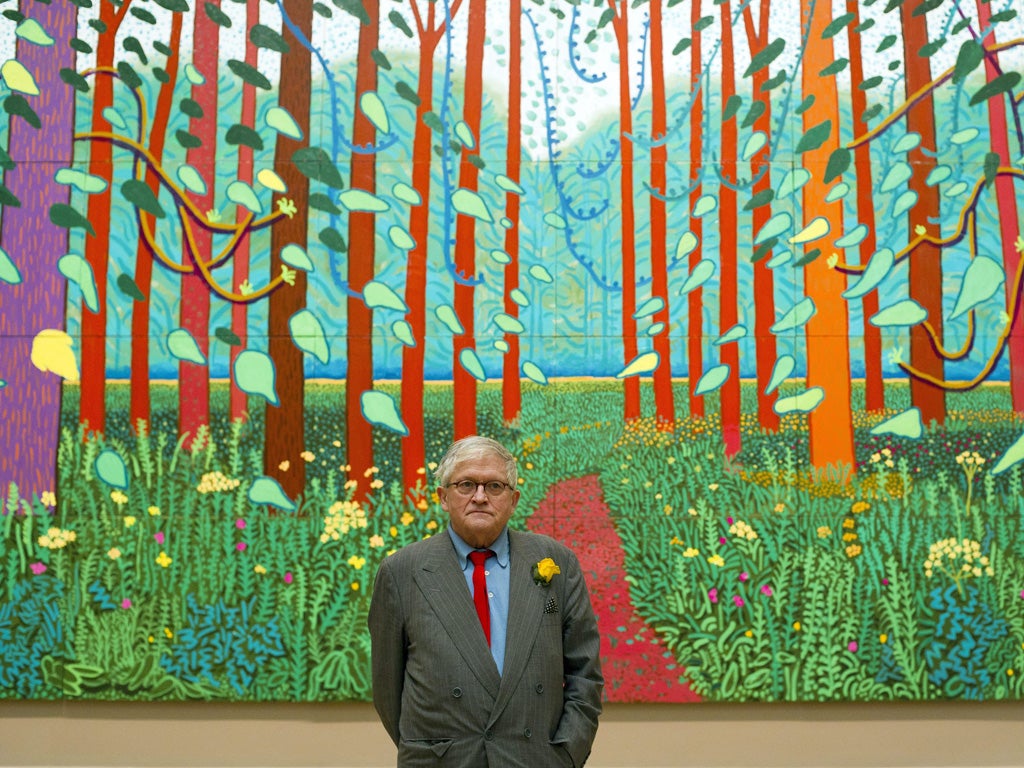

And there I was, thinking that I wasn't a Hockney fan. And how right I was, but also – hmmm – how wrong. For the first time in my years as art critic for this paper, David Hockney: A Bigger Picture forced me to append two different armchair ladies (remember them?) to the end of my review, one slumped and one cheering. At his colouristic best – the four vast seasonal studies of Three Trees in the RA's octagon, for example – Hockney is an astonishing painter, resurrecting the great traditions of English landscape art. At his worst – I still wake at night shivering over his takes on Claude's The Sermon on the Mount – he is unutterably bad. How come? Maybe he should give up smoking.

Worst show of 2012

No contest here: Damien Hirst: Two Weeks One Summer at White Cube Bermondsey was … well, this is a family newspaper. I mean, it really, really was. Let us assume that you have been so vastly successful with the sort-of-conceptual-sculpture you do that you are rumoured to have made more money from it than Picasso did. Would you then (a) go on making the sculptures aforesaid, or (b) decide that you were a painter and change your schtick? Alas, Hirst ticked (b). Perhaps the problem is that he feels trapped by his fame. Or maybe he is so beguiled by it that he believes he can do anything. He can't. The canvases in his show weren't good-bad; they were bad-bad. Bad-bad-bad. Sharks, Damien. Pills. Back is the new way forward.

Farewell

William Turnbull (1922-2012) may not have been the most radical of British sculptors, and certainly not the most self-publicising. But his well-made, well-thought-out work had an intelligence and sensibility that will see it remembered when the sculpture of showier artists is gathering dust in some far-flung Tate depository. In 1949, Turnbull, 26, turned up at the Paris studio of Constantin Brancusi, 73. If their meeting was brief and terse, the young Scot never forgot it. For the next half-century, his sculpture, in one way or another, channelled Brancusi, adding itself to the great line of European Modernism. RIP.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments