Philippe Parreno, Serpentine Gallery, London

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Time, for Philippe Parreno, is of the essence. The Algerian-born artist, who rose to prominence in the 1990s as part of a group of artists with a preference for collaboration and artistic deconstruction, has treated his first major UK exhibition, at the Serpentine Gallery, more like an event than a gallery show. Though the exhibition comprises mainly film works, one can't wander around and stop for a few minutes watching films as you please. The experience is carefully choreographed at around 25 minutes: only one film is on at any one time, and you are led towards it by window blinds that automatically lower and lift, and the coaxing sounds of speakers that beckon you, spellbound, in the right direction.

The sequence seems to begin and end with the sound of young children chanting, as though they are protesting. "No more reality!" sing the speakers around the gallery. We see children, eventually, in a film, jostling and chanting, like rather seraphic forms of their older, student counterparts, who we now witness protesting on the streets of the UK. As if to answer the children's demand, the next film we are shown, The Boy from Mars (2003) is certainly a slice of the otherworldly. A strange, delicate-looking building is filmed at night, as lights rise into the sky behind it. A water buffalo is powering the building using a set of mechanical pulleys. A set of the beast's hoofprints fill up with a milky liquid, and something whirrs into life. The buffalo and the building, like many of the characters in this exhibition, are aliens and phantoms: presences that shouldn't exist, but somehow do.

In the next film, we find ourselves riding an American train. We pass by people, who, still as melancholy statues, watch us pass by. A baseball player has stopped his game to watch us pass. To anyone who has seen photographer Paul Fusco's RFK Funeral Train series, the film is instantly recognisable as a restaging of those images, taken from on board Robert Kennedy's funeral train. The piece ends with an image of a landscape with a single tree, set against a sky of deep blue. This piece of footage is unreal, beautiful, like an Arcadia.

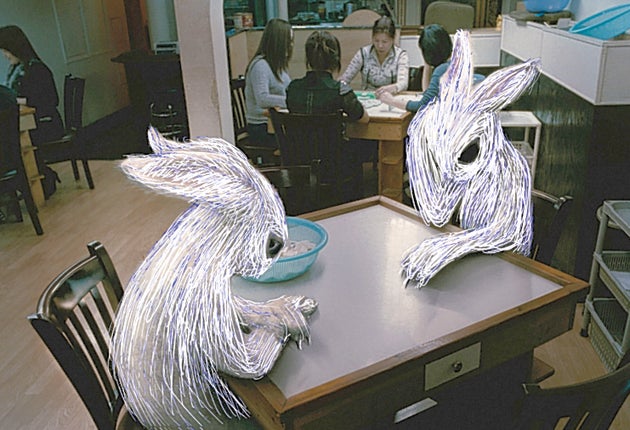

In the final film, Invisibleboy (2010), we see an illegal Chinese immigrant in New York's Chinatown, another ghost, another alien. He sees crackling, electric creatures around him, in his clothes, and under the sink. These have, in fact, been scratched into the film stock, as though the artist has created another level of invisibility for a boy who doesn't, officially, exist. Imagination and art, are aliens too. The film ends, and the children begin to chant again, and, as the blinds lift, we notice the frosty breathmarks of children on the windows. Fake snow is falling around the gallery, as though we are in an enchanted place. I walked into a frostbitten Hyde Park. A group of emerald-green parakeets, that bunch of exotic escapees that have make London parks their home, were squawking in the skeletal trees above. Those beautiful creatures couldn't have been more perfectly placed around the gallery if Parreno had introduced them to the park himself.

To 13 February (020 7402 6075)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments