Patrick Hughes: Fifty Years in Show Business, Flowers Galleries, London

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Patrick Hughes was a toddler, he slept with his mother in a cupboard beneath the stairs to shelter from Nazi bombs. Imagine what a Continental or American artist would have made of this Oedipal dream fulfilled while, as if in retribution, death rained down outside his little womb. For Hughes, however, the significance of this experience was his view of the underside of the stairs. Up became down, in became out, and Hughes never looked back. He has become the master of visual paradox and puzzle – the keyhole-shaped solid that retains the image of what the peeper saw through it, the striped tin of striped paint.

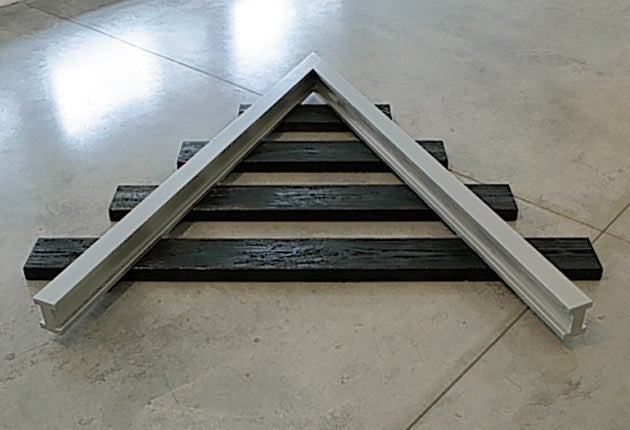

When you remove, as Hughes has, the sex and violence from surrealism, one might ask, What's left? But plenty of violence is done to conventional perceptions of space and symbol in these paintings and constructions that transgress against both myth and science. A wooden v-shaped vanishing point, atop several train tracks of diminishing width seems indecent, almost sacreligious, lying on the gallery floor, as if ripped from its niche in the temple of reason. A painting of the inside of a car shows, in the rear-view mirror, the sides of a road converging at the horizon, just like the one ahead. Is the shining prospect of the future no different, then, from the discarded past? It's a rare sobering thought in an oeuvre that is generally impish and cosy – Damien Hirst's shark, reproduced in a painted art gallery, becomes a cheerful bathtub toy.

The absence of human life in Hughes's work seems less bleak than reassuring, the world of a clever child who would rather amuse himself than suffer the demands of others, who thinks the out-of-doors is best when converted into a diagram or seen through a window. But the child is also a little god, for whom rainbows and sunshine become solid and are snatched down for playthings. Behind Hughes's gently droll facade is an absolute monarch of a dollhouse kingdom; visitors are asked to adjust their heads before entering the tilted doors. But if Hughes plays lots of tricks, he doesn't deceive; indeed, he makes us question the deceptions we take for granted. An illuminated light bulb taking the place of the sun in a paint-by-numbers landscape in effect asks why we don't go the whole hog instead of settling for such a paltry imitation of life.

The new "reverspectives", busy and bright, all aggressive hues and vertigo-inducing protrusions, are less affecting. Perhaps it is sentimental of me, but the nausea created by these large and complex constructions is not the only thing that makes me recoil. The mechanical-looking Venetian facades that shift abruptly as one passes them are no match for the real-life airiness and liquefaction of that mysterious city. The brash colours and familiar trademarks in the mini-museums in which Hughes hangs his greatest hits (reproductions of his work hang alongside a blue Matisse cut-out or a Warhold Brillo box), exemplify the commercialism and overstatement that have overtaken a once lovable England. The early works, with their endearing economy, better embody the central paradox of Hughes's work – one plucky Englishman with a few sticks and brushes making us believe him rather than our eyes.

To 3 September (www.flowersgalleries.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments