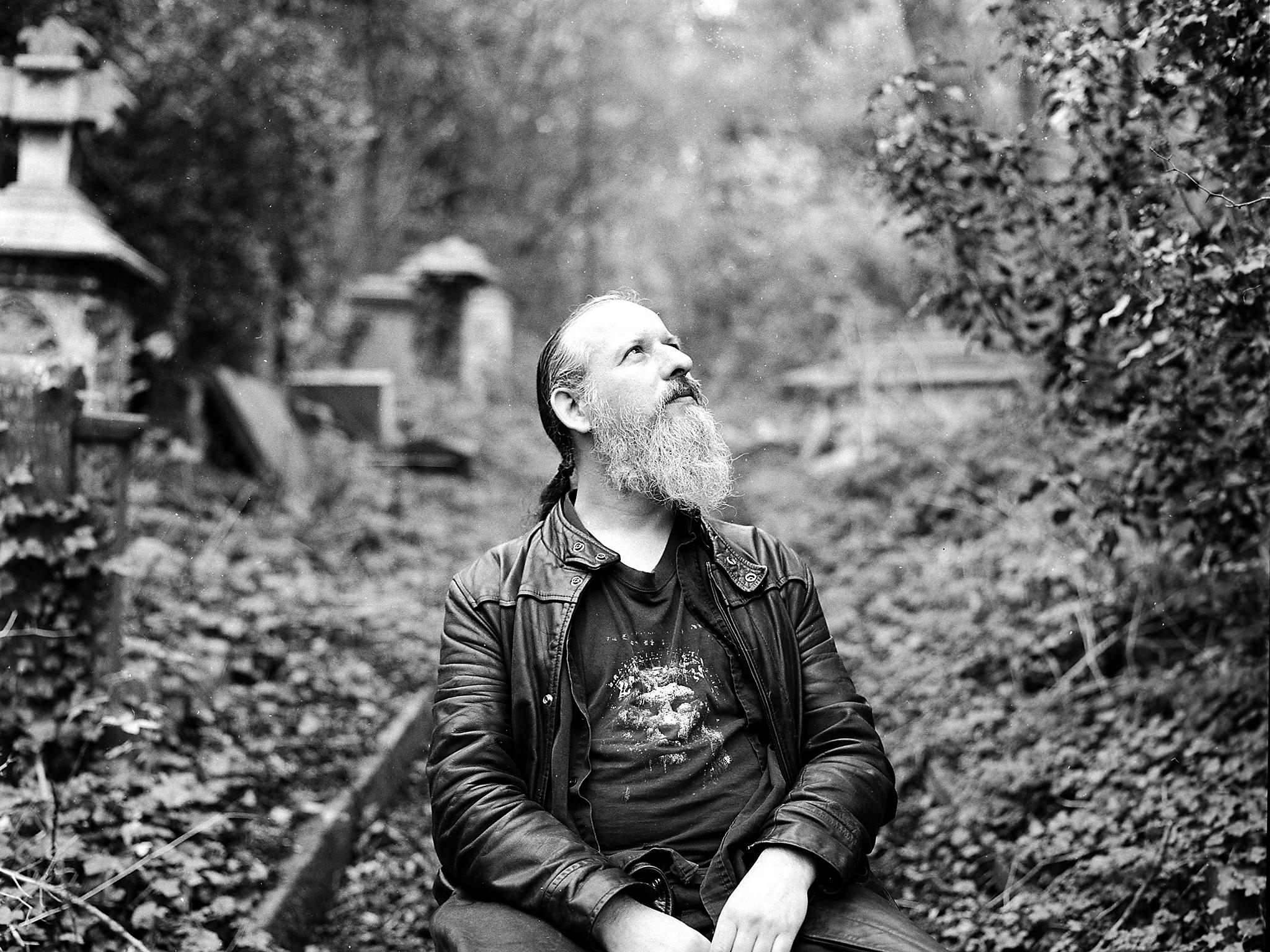

Jess Kohl’s Friends of the Dead, The Vaults, London, review: Some perch upon or linger by perhaps their favourite gravestones

The London-based photographer's series of black and white portraits capture the individuals who work and volunteer in London's most famous cemeteries

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.While most of us wile away our lives trying, as best as possible, to distract ourselves from the ego-shattering notion of our own ultimate demise, the photographs in Jess Kohl’s Friends of the Dead focus on a wily parade of individuals for whom confronting the inevitable is simply all part of a good day’s work.

Bringing together a selection of workers and volunteers from London’s “Magnificent Seven” cemeteries – the great Victorian necropolises of Abney, Tower Hamlets, Highgate, Kensal Green, Nunhead, Brompton and West Norwood – her hand-processed, black and white Arbus-esque portraits depict the tour guides, grave diggers and litter pickers who man these expansive, leaf-strewn boneyards. Some stand framed in the dusty portals of sarcophagi, some perch upon or linger by perhaps their favourite gravestones, while others are happy to be captured just simply minding their own business and going about their work.

Kohl’s work is informed by a interest in subcultures but, on the surface at least, it’s hard to find a particular aesthetic unifying this collective. While a few of the sitters betray certain tell-tale signs of a Morrissey-fixed adolescence or of a wider horror fetish – namely in their insistence on noirish garb and eye make-up, scuzzy biker leathers and general goth-chic – the rest appear strangely normal, more Bella Italia than Bela Luggosi. But if they are all here of their own choosing, then what is it exactly that underpins their membership of this morbid fraternity?

Given photography’s visual limitations the answer is almost impossible to arrive at; instead we are left guessing. In his The Incredible Lightness of Being, Milan Kundera muses “No matter how brutal life becomes, peace always reigns in the cemetery,” and perhaps it’s the noble pursuit of private space and spiritual tranquillity that ultimately unites these people – after all, each cemetery is hemmed in by the great swarm of London’s ever-expanding population, although if you stepped inside you’d never know it. In a slightly comical twist to the exhibition, Kohl has also included some portraits of Salford bard, John Cooper-Clarke, taken while he was filming a promo in Highgate. Experiencing something of a Lazarus-like comeback of late, and appearing equally as exhumed, for once we find his wry invective muted as he, too, seems to succumb to the cemetery’s calm.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments