Hokusai: Beyond the Great Wave, British Museum, review: Everything is evenly paced. You have room to breathe and reflect

The British Museum's exhibition tells the story of the Japanese artist, most famous for 'The Great Wave' – he was painting until his death at 90

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

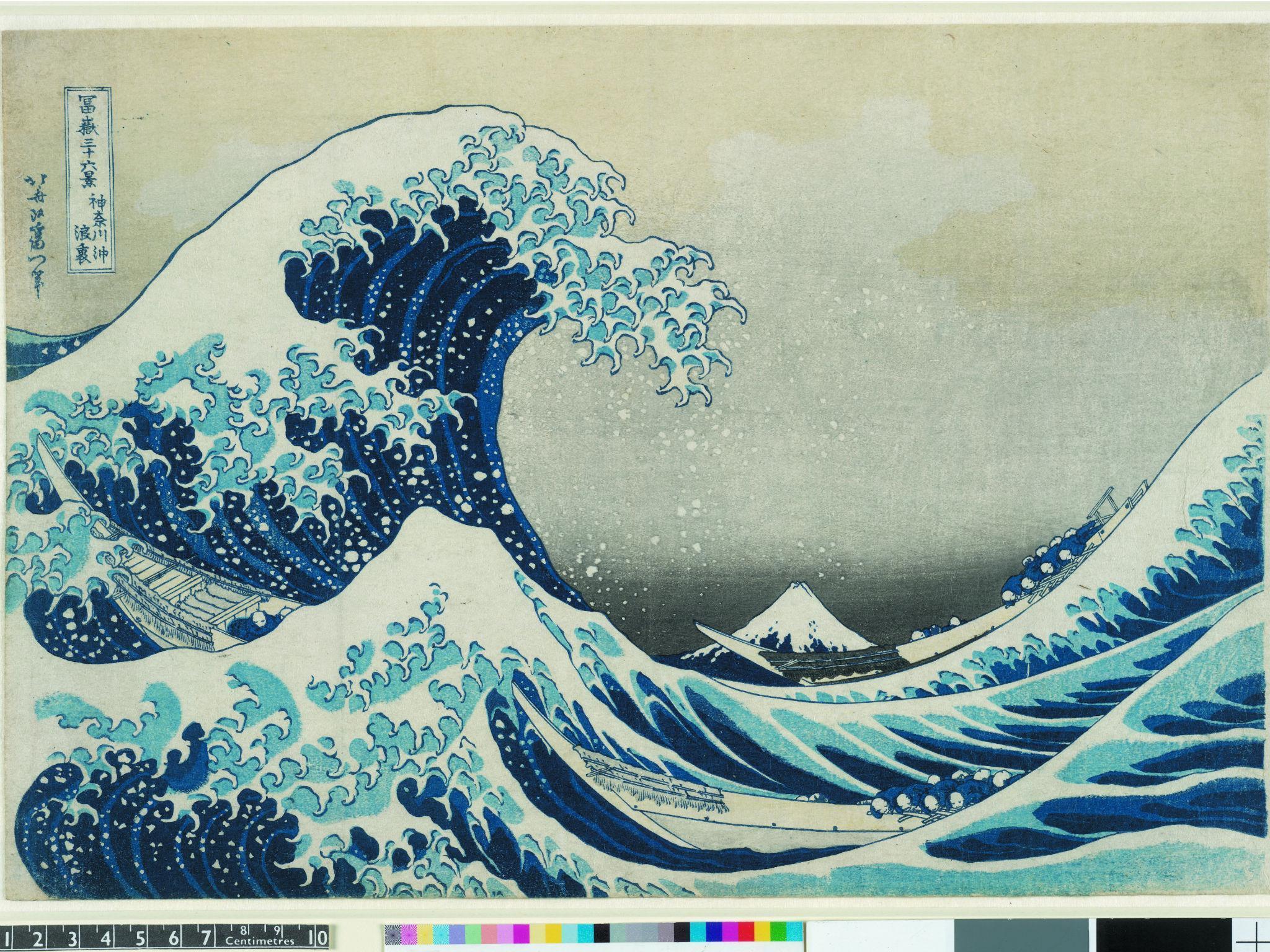

Your support makes all the difference.Things just get better and better – for some. According to Hokusai (1760-1849), nothing he drew until he reached the age of 70 was worthy of notice. Then came a commission to create a series of thirty-six views of Mount Fuji, one of which, The Great Wave is his single most instantly recognisable achievement, and the work after which this show is named.

The show itself, exhibited in the lightless upstairs exhibition space carved out of the old Reading Room of the British Museum, is the Hokusai story from start to finish, and for once this hot, unattractive, twisty-turny environment feels well managed. There are not too many works on display. Things don't come at you pell mell. Everything is evenly paced. You have room to breathe and reflect. Most of all, the design does justice to the works, which range from the smallest and the most finicky of preparatory drawings for a wood block print to the expansiveness of hanging scrolls.

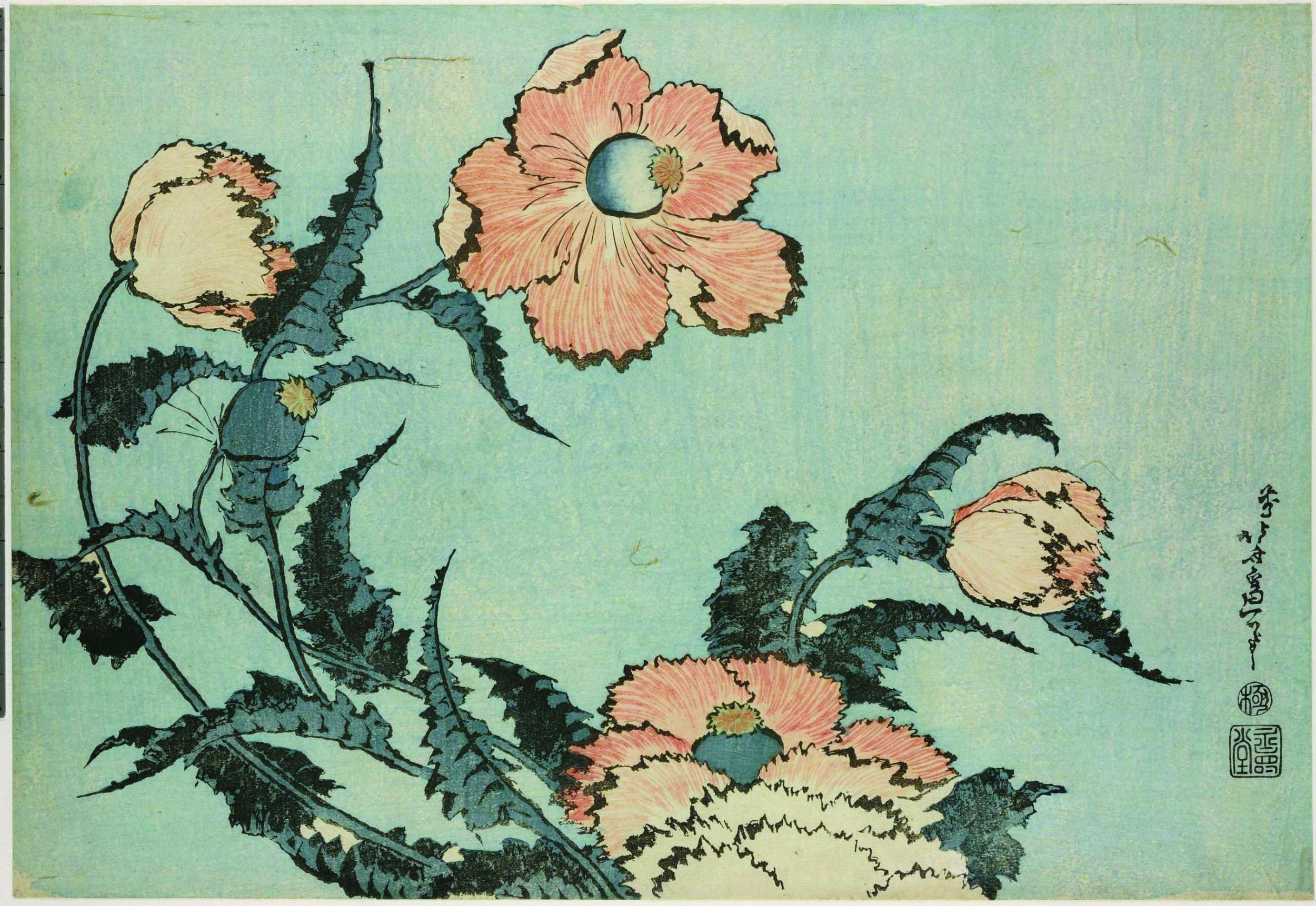

Based in Edo (now known as Tokyo), Hokusai wasn't a lone genius pleasing himself He trained as a woodblock cutter, and was a commercial artist from start to finish. His range was extraordinary – from demonic mythological beings to strutting cocks, from self-preening chrysanthemums to priests in moods of reverie, from demonic ghosts to the elegant simplicity of a hedonistic young woman staring into her mirror. He could do it all, from humorous boisterousness to meditative calm. And he never stopped. He was still hard at work in the year of his death, his 90th, and he believed that, as he aged, his talents improved. Is this true? Yes and no. The quality of the work varied throughout his life because he was a human being. But there is no denying that the best of his final works – displayed in the very last room – are the equal of his masterpieces of, well... perhaps those done at the age of 72 or 73.

Which brings us neatly back to those thirty-six views of Mount Fuji, made between 1831 and 1833. Reserve some time to look at these hard and long. They rescued his career from the doldrums – immediately before these works he was mired in debt, and his wife had just died. In 1830 he had written: “this spring, no money, no clothes, barely enough to eat.” And then came this extraordinary outpouring. Look at the views of Mount Fuji itself, that sacred place to this ever devout Buddhist, at different times of day, one red, the next pink, as one shifts from morning to late afternoon. You think back to what Monet saw when he painted in front of the facade of Rouen Cathedral at different hours of the day. You see in these prints the man who had such a profound influence upon Van Gogh. See what use he has made of Prussian Blue, a recent import from Europe.

He snatched whatever he needed. He made it his own. From the age of six on, he was so greedy to get it all down. And he did – much of it anyway.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments