Dorothea Lange: the Politics of Seeing, Barbican, London, review: These photographs have a fearless honesty

She revealed to the world exactly what life was like on the roads during the Great Depression

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.★★★★☆

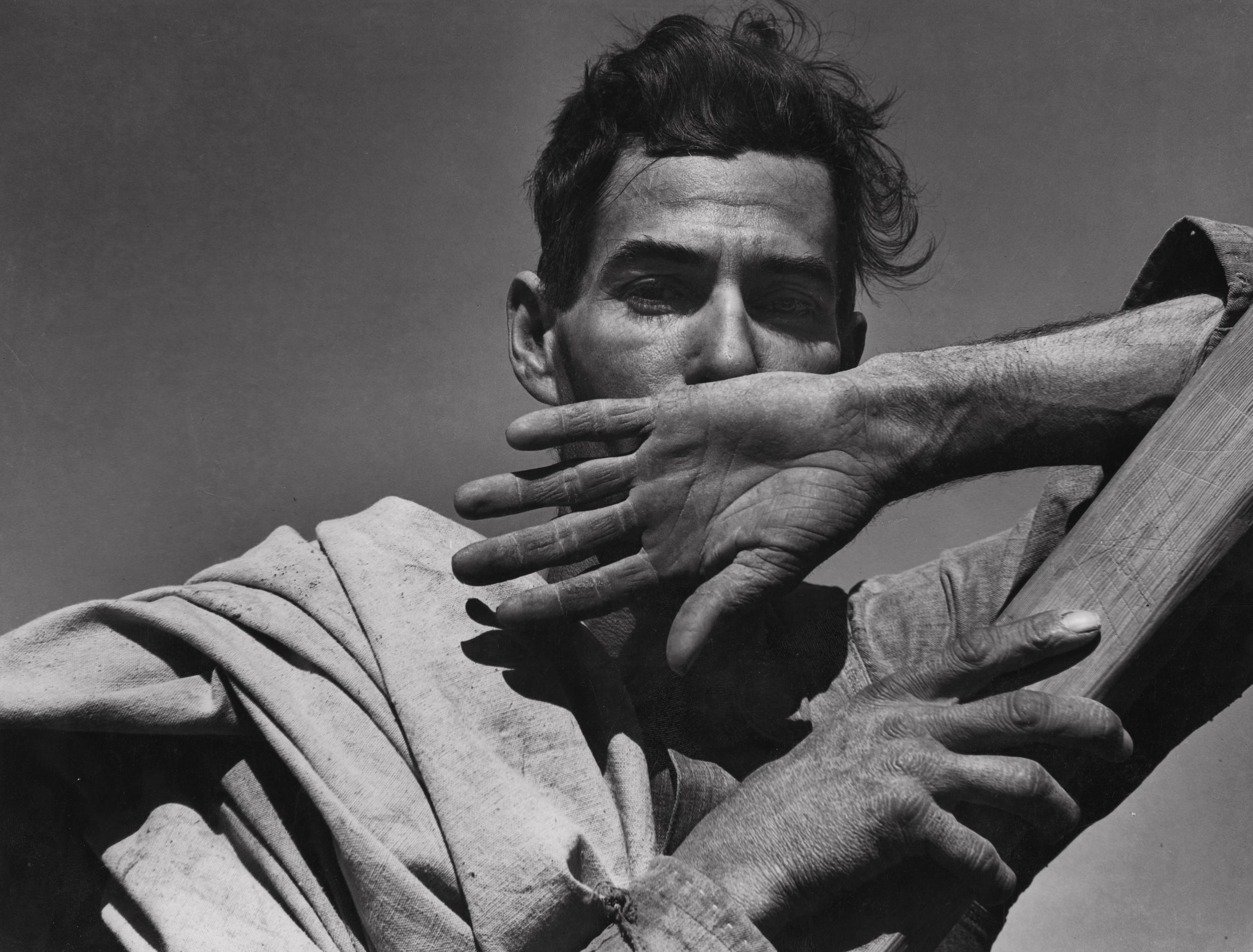

The beginning is deceptively softly, softly, if not a tad aesthetic. This retrospective of the work of the great American photographer Dorothea Lange (1895-1965), fearless documenter of the Dust Bowl years of mass enforced migration to the promised land of California, gets into gear relatively quietly.

In a studio in San Francisco during the 1920s and early 1930s, she takes portrait photographs of relatively prosperous local celebrities caught in the act of self-exposure, as if life is a tender secret, something coy and rather hidden away, to be eked out sparingly. It is all a little quiet, a little precious, a little self-enclosed.

Then something punches her in the solar plexus, shocks her into transforming herself into the heavy-camera-and-tripod-encumbered (it was a Zeiss Jurvel, by the way), boilersuited street fighting woman (all the fiercer perhaps for being hobbled by the aftermath of a childhood attack of polio) that she would remain for the rest of her professional life. She died from cancer of the oesophagus in 1965, when she was planning not only her next photographic assignment, but also the very first retrospective by a female photographer ever to be staged at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. It was to be her own, of course.

What did she see in the San Francisco Bay area to bring about such a change of heart? She saw street drifters, strikers, the desperate unemployed, some of those hundreds of thousands who were then being lured west from the drought-stricken states of Oklahoma, Kansas, Texas and Colorado, by a promise of work, better times. All an illusion. All dreams of a paradise ready to die in a puff of filthy gasoline smoke. If you ain’t got the do-re-mi, folks...

She saw, in the words of Woody Guthrie (who did the equivalent in song what she was to do with her camera, and what John Steinbeck was also to do in The Grapes of Wrath) all those dust bowl refugees plaintively wondering whether they would forever remain dust bowl refugees. And she went after them, doggedly, with her camera, getting up almost wincingly close. She revealed to the world, with a fearless directness and honesty, exactly what life was like on the roads in those terrible days: families forever travelling between here and there, in their makeshift jalopies with wheel-back chairs, skillets, nests of buckets, and battered packets of Quaker Oats strapped to the bonnet, pitching their gimcrack tents in muddy fields at day’s end.

Her most celebrated photograph, taken in 1936, was called “Migrant Mother”, and this one gets a room of its own. We see it with all the other photographs she took of the same scene: this dignified woman – her name was Florence Owens Thompson – not to be outfaced by calamity, with a baby suckling at her breast and others of her seven children swarming about her head and neck for comfort and security.

Could this really be America? Need this really be America? No, it need not. Franklin Delano Roosevelt cocked a compassionate ear.

When the camera pans back a little way, you get a fuller view of the scene: there’s the tent the family has just sold to buy food and, just beside that mother, the empty plate and the kerosene lamp. They were destitute pea pickers, pitched up outside the town on Nipomo. The crop had failed.

Until 2 September (barbican.org.uk)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments