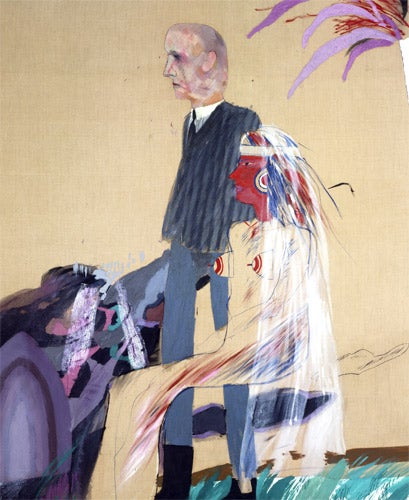

David Hockney: 1960–1968: A Marriage of Styles, Contemporary, Nottingham

When Hockney first made a splash

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.How wise is it for a brand new art centre in a major provincial city to open its doors with a show by David Hockney? Isn't the Hockney story – and aren't Hockney's works in general – just too well-known to deserve yet another outing?

In part this must be true. We know too much about Hockney. We've seen too much of Hockney. There have been several shows devoted to his works which have opened in the past two or three years, including an exhaustive – far too exhaustive – survey of his portraiture at the National Portrait Gallery, a show of his recent landscape paintings at Annely Juda in London, together with a major museum show in Swabia.

The difficulty in part has to do with Hockney himself. He has always pushed himself forward as a big part of the story of his art. He still does. It's the tale of the gutsy, cussed Yorkshire laddo with the dyed blonde hair who stormed London at the beginning of the 1960s, and then rapidly reinvented himself as a cool painter of Californian pool-side languor with a special homoerotic charge. The fact is we always seem to know what he has been doing, and in the relatively recent past he has been as much partially failing as partially succeeding. Do you remember those awful brown paintings of his dogs? Or those weak re-paintings of Picasso? Why in heaven's name did Picasso need re-painting anyway? And we can't forget them very easily either because the abiding presence of Mr Hockney is always helping to draw our attention back to them.

So why Hockney again, and what's new about this show? The new director answers the first question without a second's hesitation. A new gallery such as this one can't afford to take any chances and, well, Michael, who is as well-known as Hockney? Isn't he our first near-guaranteed crowd-pleasing, crowd-pulling blockbuster? There's a bit more to it than that though, thankfully. This show brings back into the spotlight not only some of those first major encounters with California, but it also cleverly draws our attention to the way in which Hockney himself was responding, in his very earliest paintings, to the fashionable art of his time, to minimalism and abstract expressionism, for example. Hockney is not by instinct an abstract painter – he never has been – but he makes us aware of the ways in which various kinds of austere abstraction work on us. Then, quite suddenly, as if blowing a raspberry – Hockney has always been very good at blowing raspberries – he has a bit of a joke at its expense. And he often does it as a way of saying, with quite wilful and undaunted pride, that he is a gay man in a country where homosexual acts would remain illegal for at least another half decade.

So you can read many of these early works as quite pointed acts of political defiance, not only finding a new way to paint modern, but also a new way to paint and point up a message. So some of these very early works, Going to be a Queen for Tonight (1960), for example, have a wonderful raw energy which seems to draw on the muscular excess of gestural painting, but also lightens it, and even pokes fun at it, by adding bits and pieces of text or unexpected splashes of colour, and all this seems to be saying – more shouting than saying – that, yes, there is more to life than a kind of self-enclosed spirituality.

And so, much to my surprise, to find myself looking at Hockneys such as these proved to be something quite special after all. The difficulty proved to be that after the brilliance of those early years, he then had to live with himself for the rest of his life, and that kind of thing is always difficult.

To 24 January (0115 924 2421)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments