Damien Hirst, Tate Modern, London Gillian Wearing, Whitechapel Gallery, London

As the young Turks come of age, two shows reveal that their mature selves can be both nasty and nice

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Two retrospectives in two London galleries, of two once Young British Artists two dozen years after Freeze. Time for a reappraisal, and not just of the work in the shows.

The question that occurs as you trudge from Tate Modern to White-chapel, from Damien Hirst to Gillian Wearing, is whether the term YBA ever meant anything. Hirst and Wearing are the same sort of age (born 1965 and 1963, respectively) and went to the same college (Goldsmiths). But they are so wildly different as artists that trying to organise them under a single abbreviation seems pointless, other than as a sales ploy, which is what the YBA phenomenon was.

Young British Artists were savvy. They knew about marketing. If curators refused them exhibitions, they curated their own; when no gallery would represent them, they opened shops and sold their work themselves. Written into Young British Art was a response to the market, sometimes cynical and sometimes appalled and often both at once. And that, as far as these two new shows is concerned, is as far as the term YBA goes in being a useful one to apply to Wearing and Hirst.

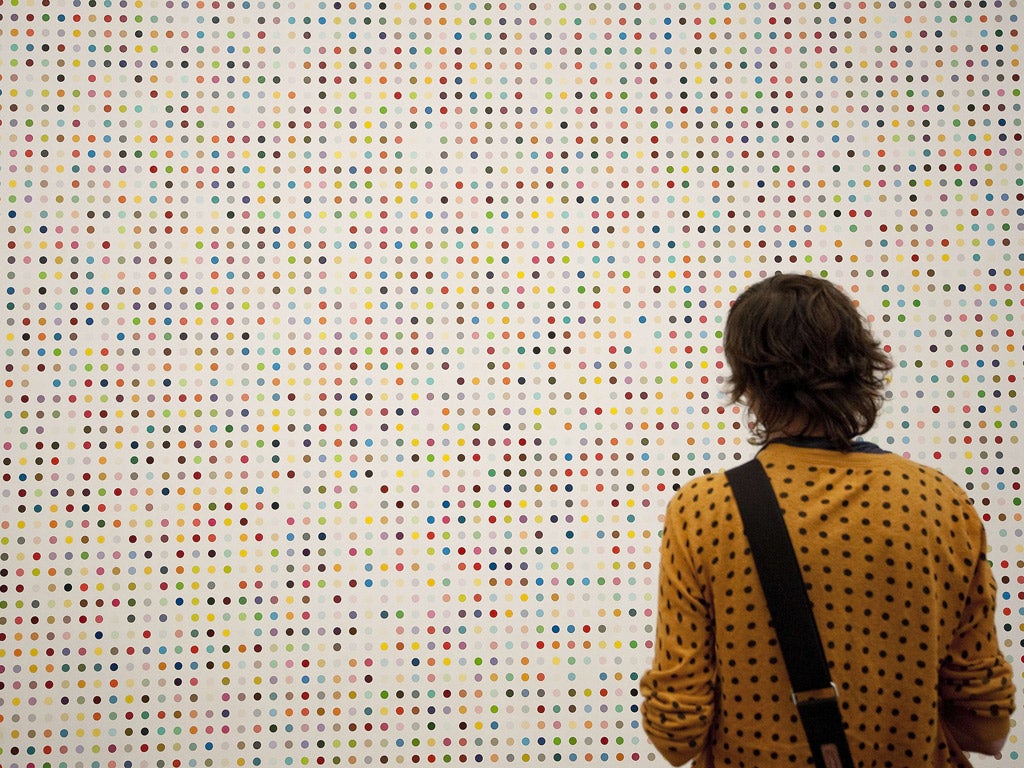

Hirst, of course, is the YBAs personified – the tyro who organised Freeze in his second year at art school, who has made more money from his art than anyone since Picasso. Hertzog & de Meuron's overblown spaces at Tate Modern might have been made with Hirst in mind; perhaps they were. As you wander through his painted spots, the flies, the anatomised sheep and sharks, the diamonds and the pills, two things strike you.

The first is that this is very expensive art, the opposite of Arte Povera: Arte Ricca, if you like. Hirst's production values are extraordinarily high. Someone has visibly been paid a lot of money to make the vitrine for A Thousand Years, to set the 8,601 diamonds – £14m's worth – in For the Love of God. Expense is built into these works, is part of their aesthetic. Seen like this, Damien Hirst's greatest artwork is Damien Hirst, an artist who outranks Charles Saatchi in the Rich List – 238th place last year, to Saatchi's 438th – a protégé turned Midas. More even than Gilbert & George, he is living sculpture.

The other thing that strikes you is that Hirst makes boy-art. Seeing a quarter of a century of his work wisely edited and well displayed, you sense a trainspotter's taste for organisation: dots of colour arranged in sequence; pills laid out with pharmacological order; flies herded just so. The flip side of this is a sense that all organising is futile, that sharks will rot no matter how well pickled, that the live butterflies in In and Out of Love are easily squashed underfoot. Beneath Hirst's gloss is always a smell of decay.

All this should add up to something admirable; for many it does. But I can't help feeling that Hirst's reputed genius stands or falls on passion, that we have to believe he is as horrified by his world as we are. And I don't believe it. Glibness and slickness are part of his intent, a constituent of the nastiness of his art. But there's another slickness, to do with finding a formula and never bothering to change it, with not having to think much because every pull at the fruit-machine ends in a row of pound signs.

Does any of this apply to Hirst's fellow YBA, Gillian Wearing? Not much. Wearing's interest is in the individual in society, whether her own family or a group of ad-libbing actors or shoppers in a mall.

The Whitechapel's show starts with a video monitor on which Wearing gyrates outside a Curry's, silent and alone – Dancing in Peckham. It ends with a series of booths, part confessional, in which members of the public wearing Gillian Wearing latex masks and wigs speak to camera: in the booth I stood in, a woman talked about incest with her brother. In between are variations on a fairly narrow theme, photographs of Wearing masked as members of her family, or films in which children are dubbed with the voices of their mothers.

A confession of my own. Seen piecemeal, it's easy to overlook Wearing's art, and I have. This retrospective shows how subtle and single-minded her career has been. Unlike Hirst's, her doubts about the world seem coherent, genuine. And behind each work are the questions: am I telling the truth? Am I capable of it? It's a very un-YBA anxiety.

Damien Hirst (020-7887 8888) to 9 Sep; Gillian Wearing (020-7522 7888) to 17 Jun

Art choice

The society portraitist Johan Zoffany reveals a great deal more of his subjects than pride and fashion at the Royal Academy in London (to 10 June). Meanwhile at Waddesdon Manor, Buckinghamshire, the enigmatic cardplayers of Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin show their hands – and the artist's skill – until 15 July.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments