Cy Twombly, Tate Modern, London

'Cycles and Seasons' spotlights an artist who hasn't put a foot wrong in a 60-year career; he takes the casual, and makes it monumental

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

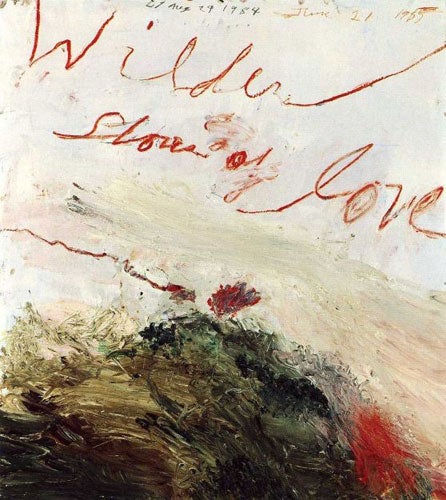

Your support makes all the difference.Look at the picture accompanying this review and you'd be forgiven for thinking that the image it reproduces is a page on which someone, in an idle moment, has doodled. Cy Twombly's scratchy marks – the ones on The Italians (1961, pictured left) say – look graphic, as though they were made by a hand resting upon a piece of paper.

Actually, The Italians is an oil painting on canvas, measures two metres by two-and-a-half, and was painted upright. Each sketched figure – a grid, a heart, things that look like tits or bums – is itself A4-size, or bigger. Far from just using his hand, Twombly's doodles must have occupied his entire body; and far from being the work of a moment, this painting must have taken days or weeks.

But why? What we see in The Italians is the magnifying of something small and quick into something big and slow. Twombly's genius – and I mean genius – lies in that transformation, in making the casual monumental.

It might be useful to think about what Twombly does in terms of photography. Blow up a photograph beyond a certain point and the dots that make it up will fall apart, leaving the image illegible. Twombly also has to deal with that problem. His canvases, looking like doodles, ask to be taken in at a single glance; but they are far too big to be seen like that.

To swallow The Italians in one go we have to find the point in the gallery where we can see the whole canvas without losing sight of its parts. Stand too near, and you will find yourself focusing on individual elements – a heart, maybe, or a splat of impasto that looks like blood or shit. Too far away these elements resolve themselves into abstract marks, like brushstrokes.

That gravitas of Twombly's work – the fact that, for all its doodliness, it dictates exactly where we have to stand to look at it – already lets us know that something more than just casual is going on. What we're seeing is history (or rather histories) in the making, among them Twombly's own. In 1957, four years before The Italians and while Rothko was busy painting colour fields, the 29-year-old artist moved from New York to Rome, where he has lived ever since. What Twombly found in the Eternal City was an eternal impulse that took in all forms of image-making, including, unexpectedly, Abstract Expressionism.

The surface of The Italians may look like a doodly bit of paper, but it also looks like graffiti – the 2nd- century scratchings on the walls of Rome's ancient seaport, Ostia Antica, or Renaissance sgraffito, or the obscene scrawls in the gents at Roma Termini.

Twombly's canvases are almost always covered with layer upon layer of overpainting through which, or on which, his figures – in graphite or crayon or pastel or house paint – appear. (Often these figures are legible or half-legible words: OLYMPIA, say, or ROMA.) His surfaces have the feel of an excavation, and that, pretty well, is what they are. Trowelled in with their archaeological paint is both the history of art and Twombly's own history as an artist.

Maybe the two are inseparable. The Tate's show, unusually clever, is subtitled "Cycles and Seasons". What you see as you walk through it are the birth and death and rebirth of an art which is both historical and personal. Each of Twombly's canvases wavers between being impeccably ancient and impeccably modern; but his work, taken as a whole, also seems to oscillate.

For years, the artist will move away from the mode of painting that seems platonically Twombly – into the vast, blackboard-ish pieces of the Veil series of the late 1960s, say, or back into sculpture in the mid-1970s. In 1988, you suddenly get the deeply un-Cy-ish Green paintings, although these fit into his oeuvre by looking for a place in history. (Made for the Venice Biennale, they match the spirit of Tiepolo with Monet's obsession with water.)

But just when you think the early Roman Twombly has gone for good, he goes back to graffiti – to the Quattro Stagioni paintings of the early 1990s, for example, which seem to follow on seamlessly from works such as The Italians painted 30 years before.

What is extraordinary in all this is how seldom Twombly has put a foot wrong in a career that is now 60 years old. (The Nini's paintings of 1971, made in memory of his dealer's dead wife, are a rare moment of lost balance. Perhaps grief made him stumble.) The show's last room contains the huge canvases, some of them three metres by five, of the 2005 Bacchus series.

Covered in wild, looped hoops of red acrylic, these take the octogenarian Twombly full circle to his pre-Roman roots as an abstract expressionist in 1950s New York. The works, violent and drippy, feel like action paintings; they might have been made by Jackson Pollock. And yet I'd guess they also take us back to Vasari's story of Giotto, who, asked to send proof of his genius to Pope Benedict XI in Rome, responded by drawing a perfect circle in red paint.

The Bacchus works are a magnificent end to this magnificent show. Miss it and you'll be sorry.

Tate Modern, London SE1 (020-7887 8888) to 14 Sept

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments