Brains: The Mind as Matter, Wellcome Collection, London

It's a brain of two halves when those little grey cells come out to play

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In a world where few mysteries remain, the human brain is a last frontier. Each of us walks around with a whitish, soft, pudding-like lump weighing roughly 1.4kg lodged at the top of our spinal column. It's responsible for processing and housing the totality of our life experience, yet despite rapid advances in neuroscience, many aspects of its inner workings are still unclear.

The latest exhibition at the Wellcome Collection is not one of its broad, socio-historical sweeps at a subject. This is not an exhibition about what the brain does as a thinking machine. Instead, it keeps a tight focus on the brain as a physical object – a thing to be measured and classified, modelled and mapped, sliced, freeze-dried and pickled, as well as sounded by the non-invasive MRI scans of today.

The 19th century is well represented, as you would expect, "brain-banking" being a facet of the Victorians' grand passion for classifying things. A collector of the brains of criminals set out to show they were different (apparently not). A medic in Philadelphia began drawing up a list of the brain weights of the eminent deceased – surely the cleverer should be heavier – but no clear picture emerged. A later pioneer proved helpfully that the brains of black people and women (shock!) were no different either. Visually, these topics have limited appeal: brains in jars, photographs of brains, and photographs of shelves of brains in jars, mostly.

To the lay observer (and I count myself one of the "incurably curious" the Wellcome has in its sights), the single most interesting aspect of the resin model of Alfred Einstein's brain is that the removal of it post-mortem went directly against its owner's wishes to be cremated intact. (Is nothing sacred?) Elsewhere, there is a ghoulish shock at seeing the brain of a 1920s suicide victim, complete with embedded bullet (though a note mysteriously asserts that this bullet "is not the fatal one"). And there is poetic justice in a phial of shrivelled tissue said to be part of the brain of the 1820s serial murderer and human-organ-supplier William Burke – probably sold to the public as a souvenir after he was tried and hanged.

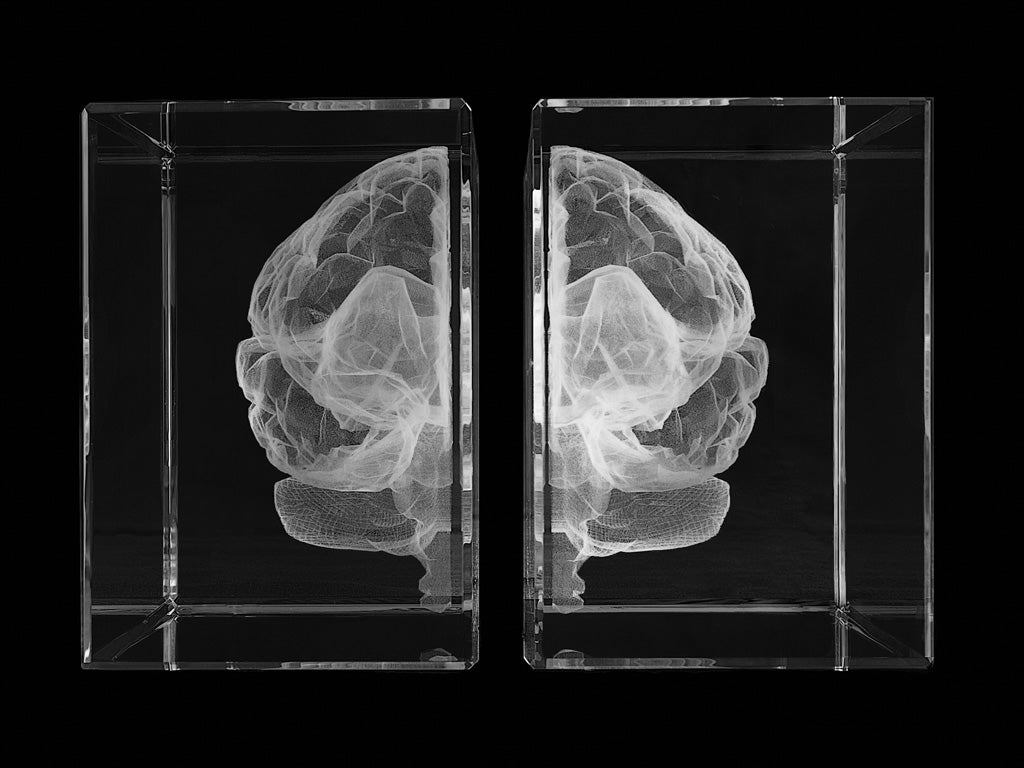

But it is the contemporary artwork in this show that stays in the mind. My Soul, a 3D representation of the brain of the artist Katharine Dowson laser-etched in two adjacent glass blocks, is a thing of airy beauty, a cumulonimbus of sheer puffed silk. Annie Cattrell's From Within casts both the interior and exterior surfaces of a human cranium to make a pair of precious objects, silvered-bronze halves of giant walnut shell.

A resin model of the system of blood vessels in the brain, down to the smallest capillaries, is strictly a model for teaching purposes. But it is a magnificent thing, ingeniously made by injecting the vascular system with liquid plastic which solidifies, allowing the surrounding tissue to be dispersed with acid. The end result is a vivid birds' nest of fine red wiring, driving home the intricacy of the neuroscientist's task in probing its function.

A digital animation purports to map brain activity in a person listening to Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring. Earphones are provided so you can note the lava-lamp activity at key points in the score, patches flickering red and orange when the music hots up.

My favourite exhibit, though, is a set of photographic portraits and interviews that draw back the veil of secrecy shrouding organ donation. Three individuals – clearly not at all spooked – were snapped the day they signed away their brains for research. Beaming Albert Webb, 93, wears a jolly jumper he knitted himself. "I shall be doing a bit of good perhaps to somebody," he said. They can have my brain, too, once I've finished with it.

To 17 Jun (admission free)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments