Body Language at the Saatchi Gallery: A mixed body of work

The Saatchi Gallery's new exhibition shows that figurative art is alive and kicking, especially in America. But the artists' vast canvases and impressive use of colour can't disguise their lack of graphic skills, says Adrian Hamilton

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The first thing to say about the Saatchi Gallery's new exhibition, Body Language, is that it is not really about the body at all. Although the gallery claims that the artists on show “explore the physical body and present a variety of reflections on the human form”, it's the last thing that most of them do.

In reality, this is a show of figurative art in which the figure appears but the body itself plays only a representational role. And none the worse for that. The human figure has returned to art, in so far as it ever really left it, and in bright colours and monumental form. So, judging from the 19 international artists displayed, is narrative art. In the case of Michael Cline, a 40-year-old US artist who lives in New York, the story is laid out in direct and sordid comic-book fashion. A naked skeletal lady, cigarette hanging from her mouth and a drinks cup in hand, stands in Woman in Doorway, O.K., a grotesquely distorted man behind her and a pale face staring through the bars of the door in the manner of Otto Dix. A group of wearied and depressed figures slouch drunk, drugged and bored around a table while a policeman enters their dive in That's That while, in the most emotionally and physically contorted picture, Free Turn, an aproned figure lies sprawled backwards, amid a visual cacophony of signs and inscriptions around an overturned cardboard box, a clear play on Mantegna's foreshortened figure of the Dead Christ.

At the other end of the emotional spectrum, the Japanese artist, Makiko Kudo, paints figures of young girls outstretched amidst verdant undergrowth in Invisible, or on a branch of a forest in Burning Red, while in See Season the girl lies on her back while sprite figures in pink move away from her in different directions. The effect is of both dreaminess and dislocation, of lost innocence and drifting life. You know there's a story there but, as in Vermeer, it is a private one beyond our knowing.

Kudo is unusual in that she only hints at the story behind. Most of the rest state it as baldly as possible. In Mother and Child II, Chantal Joffe, who works in London, faces the viewer with a self-portrait of the artist naked and leaning down to hold up the child as it tries to walk, her face not so much tender as strained in its tight lips and eyes that would be elsewhere. A multi-imaged wall of several dozen small paintings, called Untitled, describe the life, loves and friendships of a pre-pubescent and adolescent girl either side of a group of lurid and brutally painted pictures of group sex and male sexualised womanhood. The painting is fluid but the message is brutish and short.

In the opening room, Henry Taylor, an African-American from California, pictures his brother Gene as a tunnel rat, a giant light bulb indicating the idea that comes to him, while his street scenes contain stories of mixed-race sex and idle mobile phone thoughts of a conversation to be had.

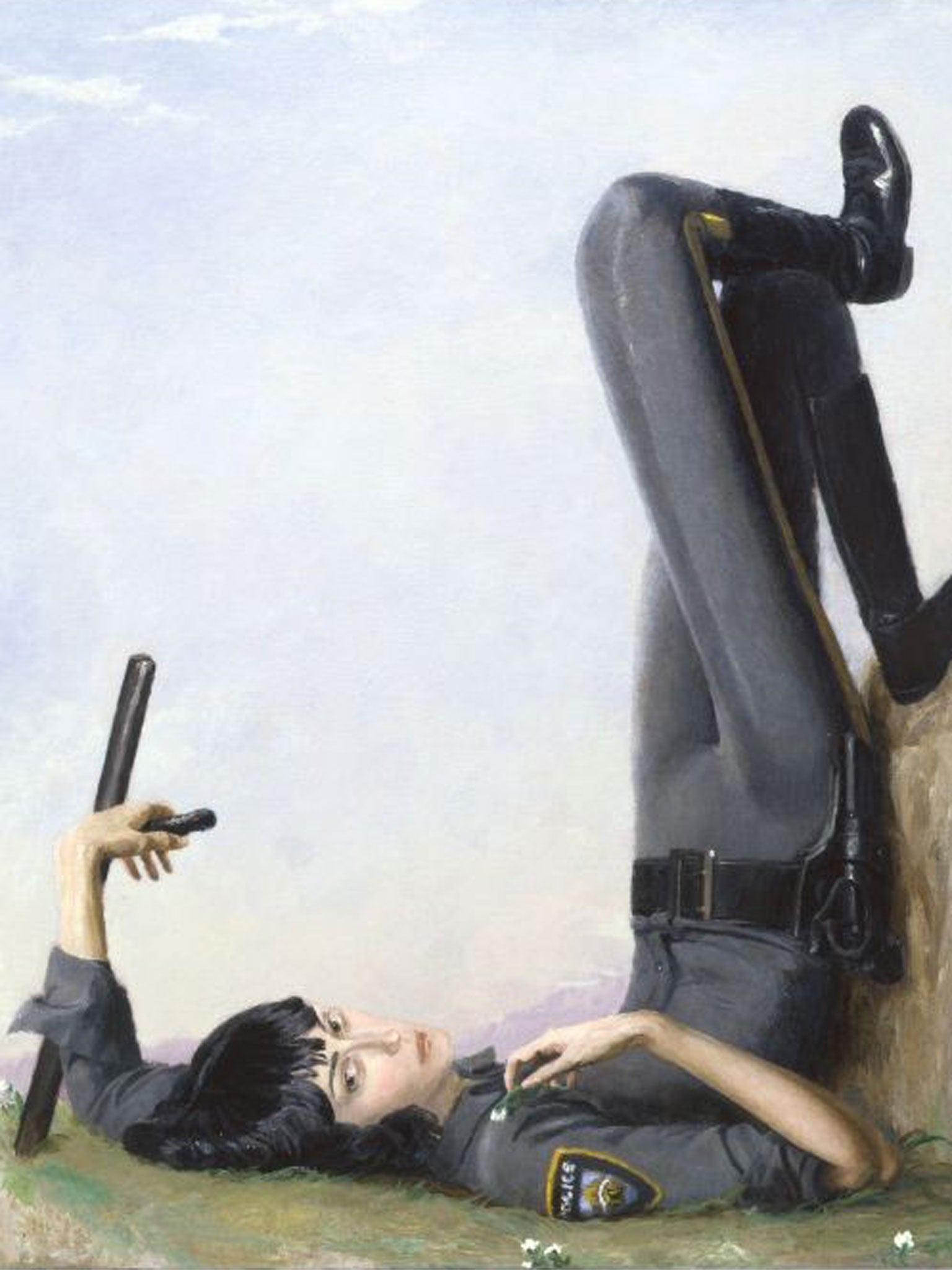

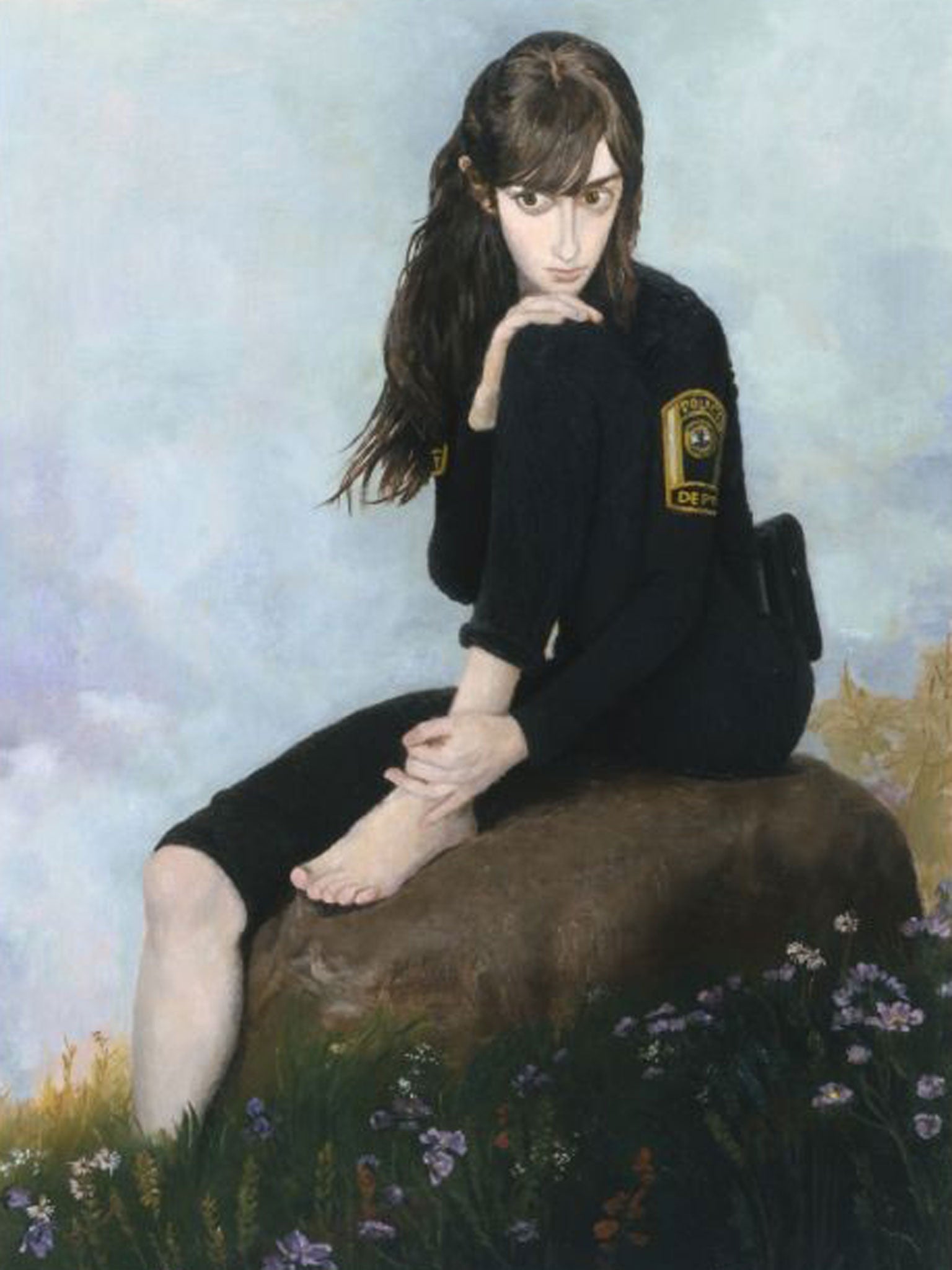

Jansson Stegner, a Mid-Westerner working in New York, is represented by a series of Pop Art images of policewomen, alternately posing in contemplative and seductive stances in contrast to the blue/grey uniforms and batons of their calling, the populist images of advertising and fiction clashing with the emblems of authority, while the Russian artist, Denis Tarasov imposes painted, life-size images of male and female figures onto the gravestones and memorials of the cemetery, suggesting the figures of the dead coming out as they once were, in contrast with what they have now become.

A deliberate twist to imagery – or “subversion” to use the word so beloved of curators – is certainly one common thread running through these works. But then the chief characteristic that comes across is actually a literalness of statement. The irony of postmodernism is largely absent, except in some of the tiresome titles. The West Coast artist, Nathan Mabry, entitles his steel and bronze figures A Very Touching Moment, as one American figure rests his cheek on his hand and the two figures tongue each other, but jokey titling does not deepen a simple if not simplistic message.

Kasper Kovitz's powerful busts of distinguished Basque heroes, carved out of Iberico ham set in concrete, have a sense of impermanence and decay emanating from their organic matter, but their power really comes from the sculpted force of fat on meat in their satirised faces. Justin Matherly's twisted human shapes in glass-reinforced concrete are burdened with such long titles – As long as its truth and purity remain inviolate and no blasphemous rationality dares approach its sacred confines (Guilelessly open and deeply hidden) and The significant and difficult run deep and do not flow on the surface (The beautiful and useful are not to be grasped at a glance) – that they lose their force in the telling. Tanyth Berkeley's C-prints of women and the odd transsexual owe a great deal to Cindy Sherman in their portrayal of attitude, but lack her layers of meaning and wit.

Layering of meaning is not the ambition of these artists. What the works have instead is size. It may be due to the preference of the curators. It may also be influenced by the nature of the gallery, which suits the big and the brash to fill its bright white interiors. But the paintings tend towards the huge – a couple of metres in height and up to four metres in width in the case of Helen Verhoeven's two Event paintings, and more than 8.5 metres wide in the case of Eddie Martinez's The Feast.

The painters can get away with this because of their open brushwork and bravura use of colour. Oil and acrylic paint are slapped on with abandon. When a point is made, as in Dana Schutz's Reformers, in which the figures smash up a table containing a prostrate body, or in her more formally crafted Singed Picnic, in which the figures are seared with black, fuzzy lines, the message is rammed home with a heavy hammer, or rather a big brush or paint spray can. The influences here are Pop Art, German Expressionism and Art Brut, not the painterly experiments of Matisse and Picasso.

Missing is any great graphic ability. Presumably the art schools attended by these painters and sculptors no longer teach drawing. Colour and shape carry the composition, which is fine so far as this kind of narrative art is concerned. But it doesn't do if the exhibition were to be really about the body, when you need a grasp of the structure of the physical if you want to make it the vehicle of your comment on the world and your place in it, as Jenny Saville does with painting and Sarah Lucas with sculpture.

There is one exception to this and it comes in the final gallery. Andra Ursuta is a Romanian sculptor, yet another featured in this exhibition who lives and works in New York. Her work is savage, direct and based on casts of her own body. In Crush from 2011, her sprawled and prostrate figure, emaciated in its urethane case, lies twisted in the manner of the casts made of Pompeii's fleeing victims. The sense of wasted humanity is made all the more poignant by the way she spatters silicone across the body.

In Vandal Lust, the body is this time clothed in the costume of her native Romania, now prostrate beneath a ramshackle trebuchet, made of wood, cardboard and metal, which had hurled her against the wall. I'm not sure how necessary the ramshackle machine is, but the message of humanity crushed by the power of the Soviet state is grim and powerful. At last, the body is the message.

Body Language is an exhibition of work from the past five years by established artists which proves that figurative art is alive and brightly kicking, especially in America where it has been sidelined for so long by abstract expressionism and its successors. Whether it suggests any new direction is more doubtful.

Body Language, Saatchi Gallery, London SW3 (saatchigallery.com) to 16 March

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments