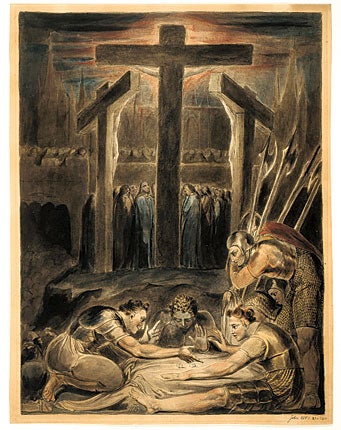

Blake 1809, Tate Britain, London

This exhibition was given a critical drubbing when it opened 200 years ago. Since then the painter's reputation has gone from lunatic to visionary, so how do those works look now?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It is galling to know that, however unpleasant my review of Tate Britain's Blake 1809, it could never live up to the standards of bile set by the critic of The Examiner at the exhibition's first opening two centuries ago.

Of this, the only solo show William Blake had in his lifetime, Robert Hunt wrote: "The poor man fancies himself a great master, having painted a few wretched pictures, blotted and blurred and very badly drawn." The artist's accompanying Descriptive Catalogue, reprinted now by the Tate, was "a farrago of nonsense ... the wild effusions of a distempered brain". Warming to his theme, the vulpine Hunt concluded that Blake was "an unfortunate lunatic", and retired for the night a happy man. Not so William Blake, The Examiner's notice being the only one his show received.

So various questions spring to mind, the first being why Tate Britain has chosen to restage one of the greatest duds in the history of British art. The answer, of course, is that modern viewers will, as one, take sides with Blake against Hunt. In the 200 years that separate the first and second outings of this show, the unfortunate lunatic has entered the canon as a national treasure, a poet and visionary on a par with Milton and Turner.

This transformation is an object lesson in the fickleness of art history. When Blake died in 1827, his reputation stood much where Hunt had left it, which is to say in tatters. It took 40 years and the anti-Academic convolutions of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood – Dante Gabriel Rossetti was a particular fan – to begin the artist's long walk to reclamation. The link between Blake's genius and his swivel eyes established, he was taken up in the 1890s by another self-professed visionary, William Butler Yeats. So convinced was Yeats of the artist's greatness that he deduced Blake could only have been Irish, the lost offspring of a man called O'Neill. (He wasn't.)

By the turn of the 20th century, Blake the Flake had been replaced by Blake the Troubled Genius. In the introduction to his 1927 study of the artist, the pacifist Max Plowman could confidently write that "the day seems not far distant when ... apologies will be unnecessary and ... Blake will be no longer regarded as a narcotic for numbskulls." Instead, he has been claimed in turn by Surrealists, hippies, Allen Ginsberg, Marxists, Bob Dylan, university undergraduates and anyone else for whom madness might usefully be construed as an act of political rebellion.

Who was right – history or Hunt? Blake's original show was held over his brother James's hosiery shop, and the few visitors it attracted were charged an eye-watering two shillings and sixpence for entry. (This did include a copy of the aforementioned farrago of nonsense.) There were 16 works in the 1809 exhibition, of which 10 have been brought together here. The missing six, including a vast, lost tempera-on-canvas painting, The Ancient Britons, are represented by white spaces. As an indicator of what Blake's contemporaries might have expect

ed to see in a gallery, the Tate has also hung one wall with pictures painted in or around 1809, including a memorable scene by Turner and a deeply forgettable one by William Mulready.

Nonetheless, the problem remains one of context. Tate Britain is the national pantheon of British art. For a painter to get a solo show there, he must, by definition, be great: Blake 1809 is, inevitably, a self-fulfilling prophecy. No matter how punctilious its curating, an exhibition held in Room 8 in 2009 can never replicate the sense of one held in a room over a shop in 1809. James Blake dealt in fine stuff for gentlefolk, goods well made. Whatever else they might have been, his brother's goods were not that. To this extent, Robert Hunt was right: pictures such as The Spiritual Form of Nelson Guiding Leviathan are badly painted, their drawing naive, their composition wonky. But then their point was to be, in various ways, non-conformist; and that they certainly are.

I'll own up here to finding Blake a great poet but a tiresome artist, the eccentricity of his drawn vision (or visions) oddly unconvincing. It is now almost impossible to see him other than through the historical spectacles of Yeats and Rossetti, Ginsberg and Dylan. Although I suspect it didn't mean to do so, the Tate's show gives a glimpse of how Blake may have looked before these gentlemen got their mitts on him; to see what the glint-eyed Hunt saw.

To 4 October (020-7887 8888)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments