Basquiat, Boom For Real, Barbican Art Gallery, London, review: The art itself is drowned by fame-frothy noise and visuals

This is first large-scale exhibition in the UK of the work of the self-taught American artist Jean-Michel Basquiat who died at the age of 27 in 1988

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.This is not so much an art exhibition as an excessively documented account of a social and political phenomenon called Jean-Michel Basquiat, a not especially socially disadvantaged black artist from Brooklyn (his mother was taking him to exhibitions at MoMa as a child), who was born in 1960, died from a heroin overdose in 1988, and whose paintings now sell for upwards of $100 million dollars at auction. There’s no mention of his death in this show. It’s all about him being on the ever more exciting up and up.

Is that a criticism? Yes, because the art itself – the exhibition’s fundamental reason for being, surely – gets a little drowned out by all the circumambient, fame-frothy noise and visuals – what circles he moved in; how he got to know Warhol, and so on. All this attention to the detailing of an individual life – the least scrap of signed paper, the most inept scrawling on a matchbox, is worthy of our reverent scrutiny, apparently – puts the cart before the horse. It leads us to assume that Basquiat is, we have already all agreed, a great and highly significant artist without much trying to prove that to be the case.

Well, there’s nowt quite so queer as commerce, you might say. So we begin, right beside the entrance to the show, with a display of Basquiat T-shirts, Basquiat books, Basquiat this, that and the other. Then the noise of a rasping sax seizes us by the throat – the boy loved nothing more than Bebop & Bird – and we stare up at a giant screen where he is dancing in his studio. The art of any real significance comes drip by intermittent drip between the many diversions which oblige us to reflect upon everything to do with the life that he lived in New York City from 1979 on, when he had his first work in a show.

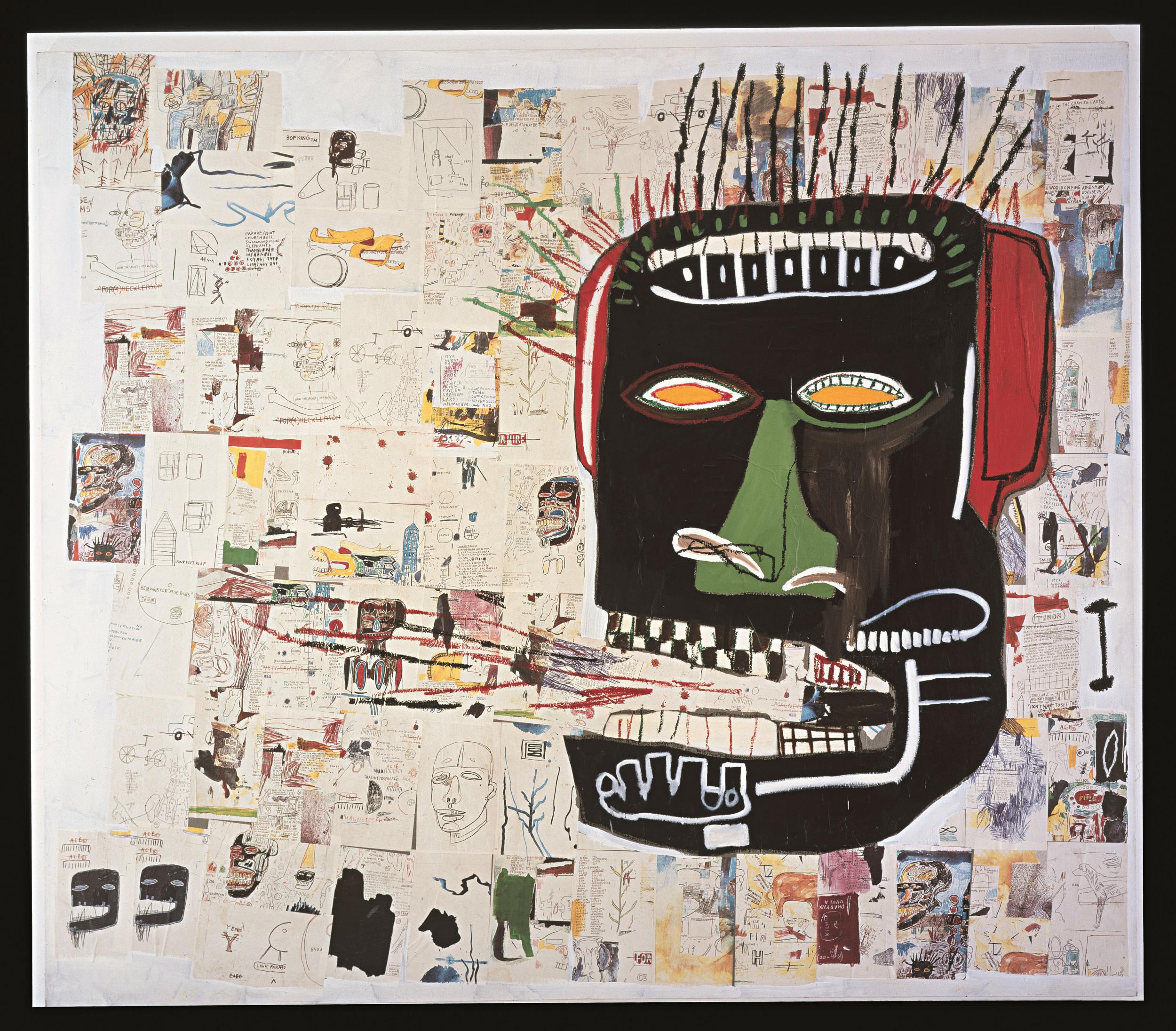

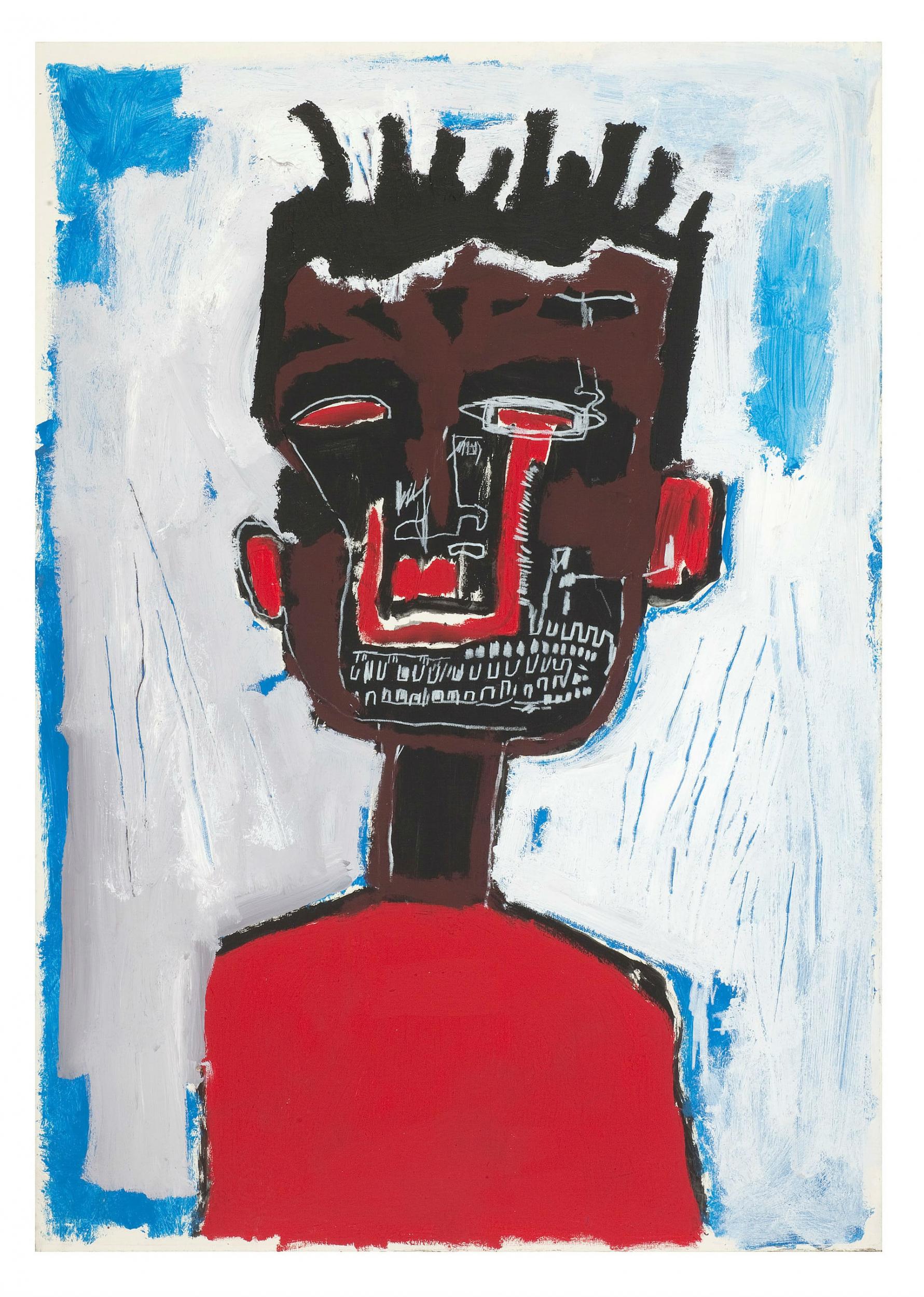

What is the work itself like then? It’s frenzied, on the hoof, and often made, we’re told, to the accompaniment of music drilling in the ear. As a child, he had ambitions to be a cartoonist, and cartooning, throughout, is a big part of what he did. The work is wild, unpremeditated, improvisatory, with all the violent, ad-libbing elasticity of the moment. The cartooning comes compacted together with text, daubings of furious colour swatches, the snatching of found images from anywhere and everywhere.

He made his art from the detritus of the street, cigarette butts, TV-and-film besottedness. He loved the image of the boxer fighting his way through. One of the most memorable images in the entire show is a photograph of Basquiat standing next to Warhol taken by Michael Halsband in 1985. The two of them pose together in their Everlast boxing shorts, gloved fists crossed over puny chests, Warhol in his ridiculous electrified blond wig.

Basquiat had sought Warhol out. They collaborated – there’s even a very bad, rushed painting here of the two of them together, done by Basquiat in no time at all, and delivered wet. Warhol later befriended him, and even leased him an apartment at 57 Great Jones Street, Manhattan. Is the original lease of that apartment here, in one of the vitrines? Of course it is! How could it not be, in all its dreary authenticity, rendered sparklingly make-believe only by the fact that we can read those two magical, dead names, rendered all the more make-believe by tiptoeingly reverential, wide-eyed exhibitions such as this one?

Why were we all born too late for such dangerous fun?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments