Alberto Giacometti, Tate Modern, review: It would have been refreshing to see an early painting or two

The UK’s first major retrospective of Alberto Giacometti for 20 years is on show at Tate Modern

The human form divine... That snatch of poetry by William Blake reverberates, oddly, when in the extended company of Alberto Giacometti. Why so? Because it both does and does not quite fit with what we see in front of us – and Giacometti is always about dramatic, headlong confrontation, a ferocious, street-corner button-holing. He never examines the world side-on, with a casual irony. He is never at half throttle, gently coasting. He is always pushing his impulses to the limit. And if there is indeed a measure of divinity in the attenuated human forms of Giacometti, those forever oncoming heads and bodies, it is a scarified, bruised, off-kilter species of divinity. Divinity then? More a strangely chilling spiritual haunting.

This excellent show at Tate Modern is the largest and most thorough examination of Giacometti’s achievements in a quarter of a century (there has been much fruitful delving in the archives of the Giacometti Foundation in Paris), and it begins, in Room 1, with a kind of triumphalist display of his heads, surging towards us, wave upon wave of them, on white plinths up the room, meeting us eye to eye. They cluster. They interrogate, unnervingly. What variety there is here! We see Giacometti passing from the tamely well rendered realism of youth to the darker, more tense and pinched onset of his maturity. There are real oddities here too. Pleasing ones. We flit from a plaster bust of Flora Mayo, a blowsy, crudely fashioned pancake of a face with pouty lips made when he was just 25, to an exquisite, thumb-high representation of the head of Simone de Beauvoir of 1946.

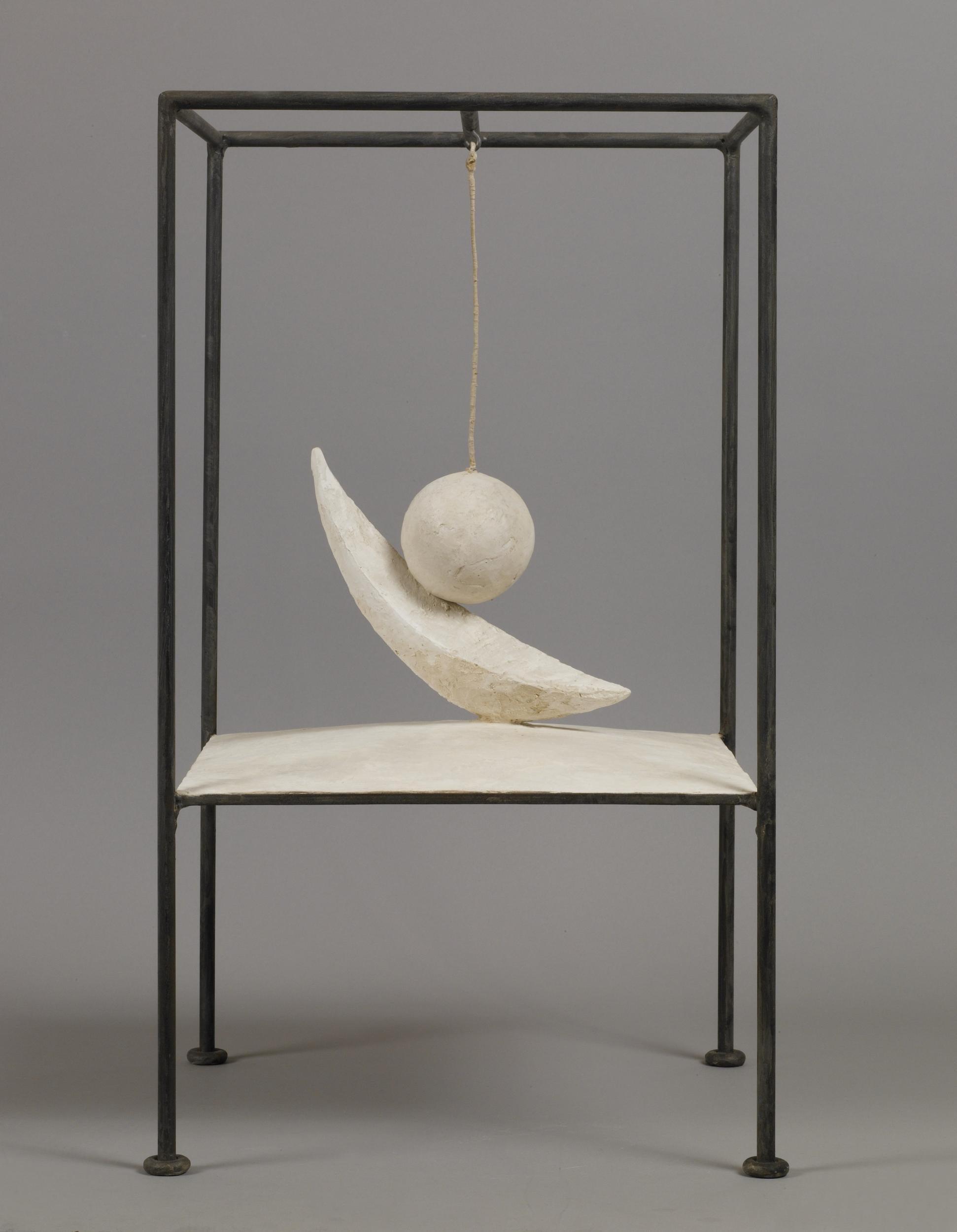

Surrealism and existentialism are both useful handles, the first throughout the 1920s, until Breton excommunicated him from the Brotherhood for being too shamelessly realistic, the second after the grey desolations of the Second World War, when he had found himself marooned in Geneva. You see why Giacometti readily embraced both – and why he was readily embraced by them. Sartre loved him. Could anyone bring over the nasty viscosity of the world better than Giacometti, its chilliness, its godlessness, its sense that the human form was perhaps an ever-diminishing, anti-heroic irrelevance?

The greatest single work in the show is something created beneath the capacious umbrella of surrealism. It is called Woman with her Throat Cut (1932) and it is in Room 4. Hurry to it. It is very unexpected. The only other Giacometti remotely resembling it that I have ever seen lives in the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice. It is bronze, with an eerily dull brown patina, which appears to show human disjecta membra uneasily shifting or slithering away from each other in disgust. Is that a rib cage? It is both insect-like and a tad botanic; it is also at floor level, which seems to increase its enthralling repulsiveness. Though utterly passive, it looks irredeemably violent. It could leave its imprint on your shoe. Room 3 surprises and delights too, with its display of the decorative objects – lamps, vases, jewellery – that he was making in the 1930s.

Two disappointments. It would have been refreshing to see an early painting or two – that aspect of the recent Giacometti show at the National Portrait Gallery was revelatory. And some of the late works in the last gallery cause the show to end on a bit of a whimper. Why show works which demonstrate only his ability to go on repeating himself without the energy and the focus of the past? Why not draw a respectful veil over his sad, late decline?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments