Why people used to look so serious in photos but now have big smiles

How did we learn to smile in front of the lens?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Smiling is a biological reflex. Babies practice smiling as soon as they are born, their bodies rehearsing this essential human gesture.

But to smile for the camera, to mug and pose, is strictly a learned habit. Historians say that the photographic grin not only a recent ritual, but also a somewhat artificial one: abetted by the camera industry, and entwined with the rise of cheerfulness as an American cultural norm.

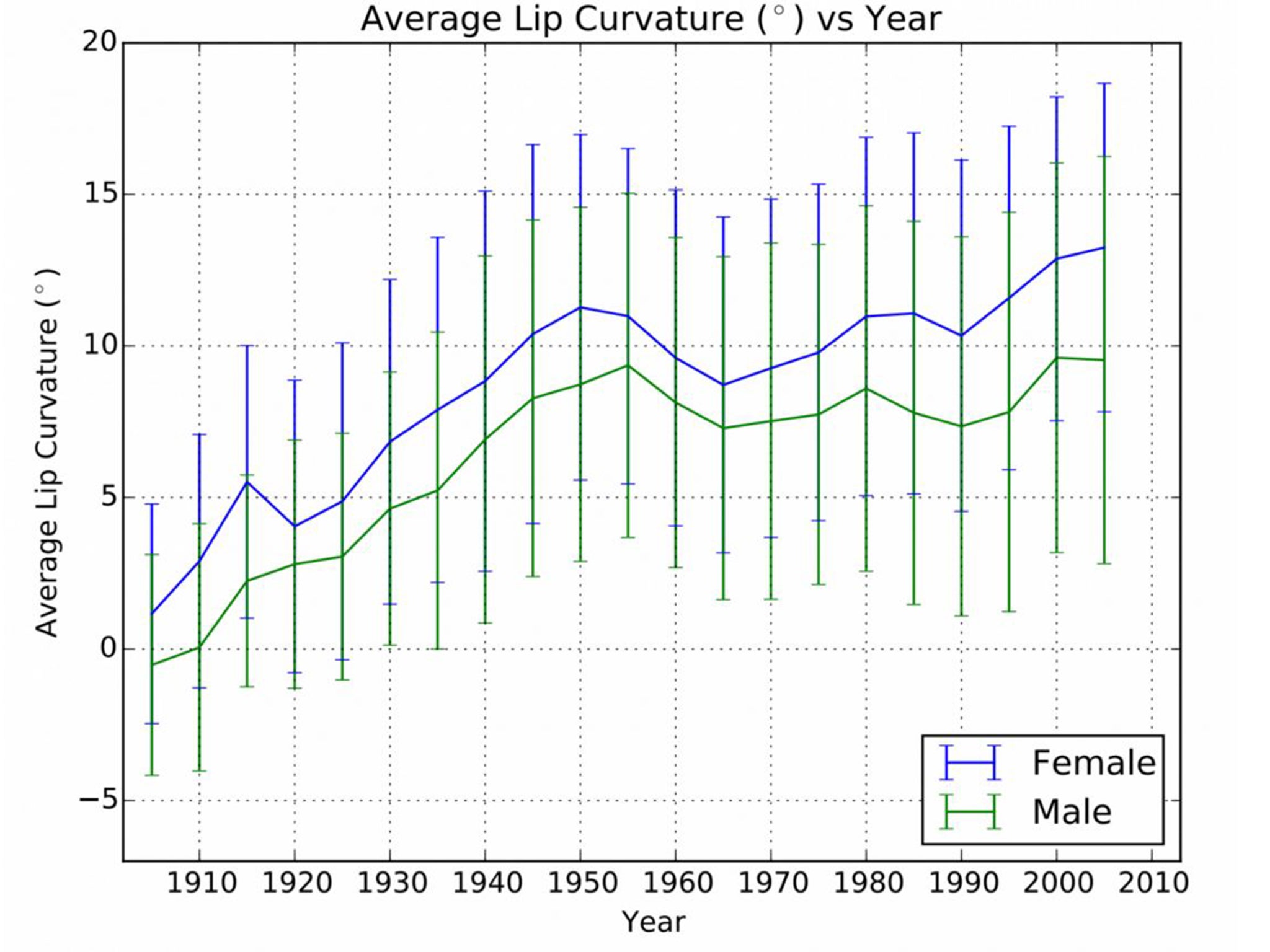

Nowhere is the trend easier to spot than in this chart from researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, and Brown, who recently analysed over 37,000 senior yearbook portraits spanning 1905 to 2013. They measured the depth of each person’s smile, plotting the average geometries of their mouths over time.

As you can see in the chart below, high school students in the 1910s didn’t smile much at all. The chart shows their lip angles are close to zero, meaning their mouths were mostly flat. But by the post World War II period, people were openly grinning in their yearbook photos.

The data suggest that in today’s yearbooks, men are smiling about as intensely as they did in the 1950s, and women are smiling more than ever.

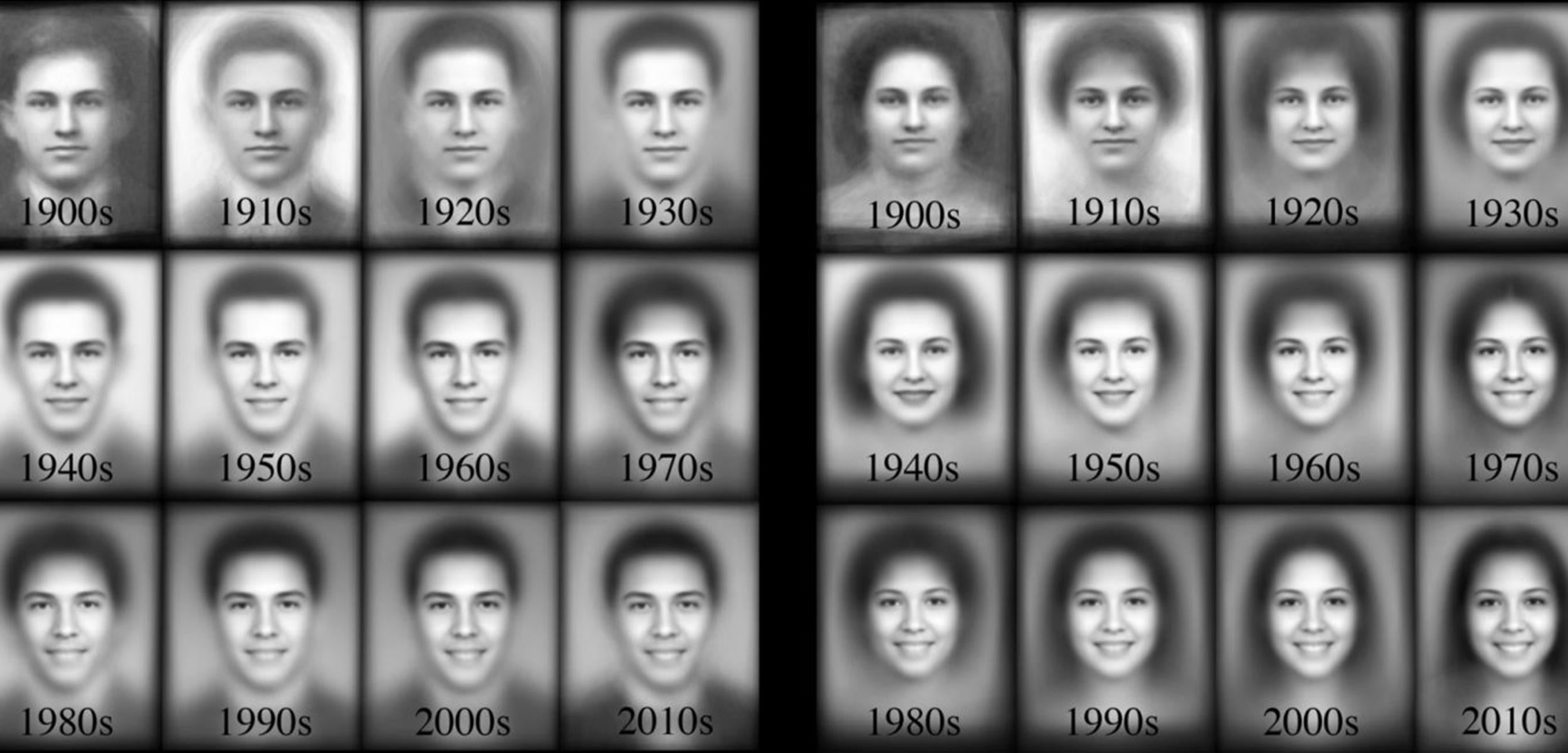

Here is a sequence of the average faces from each decade, as generated by the researchers. The oldest photos from the early 1900s have dead eyes and the grimace of a cadaver. The more recent photos show a proliferation of grins, especially among women.

The 949 yearbooks that the researchers looked through were not part of a random sample, so their paper (forthcoming at a computer vision conference in December) is not a definitive account of trends in school portraits. But their analysis offers fresh quantitative evidence for a massive cultural shift in American history. Over the course of the past century, happiness has replaced seriousness as the default emotion for photography, and for portraiture in general.

How did this happen? How did we, as a nation, learn to smile in front of the lens?

A classic — but insufficient — explanation blames early cameras, which had long exposure times requiring subjects to sit still for several minutes. In those drawn-out sessions, a neutral expression was easier to hold than a smile.

But even by the late 1800s, when the technology improved to the point that photographers could easily freeze a smile onto film, people still preferred serious, pensive, or even sad poses for their photos.

Historian Christina Kotchemidova argues that people were motivated mainly by cultural forces, not practical considerations. “Etiquette codes of the past demanded that the mouth be carefully controlled; beauty standards likewise called for a small mouth,” she says in her 2005 paper on the history of smiling in photographs.

Though photography was still relatively new in the 1850s, portraiture was not, and tradition said that proper people should not grin or bare their teeth in their pictures. Big smiles were considered silly, childish, or downright wicked.

“In the fine arts a grin was only characteristic of peasants, drunkards, children, and halfwits, suggesting low class or some other deficiency,” Kotchemidova writes, citing research from historian Fred Schroeder.

The camera changed how people got their portraits taken, but it didn’t change their notions of etiquette and beauty, at least not in the early days. Shooting in the 1840s, British portrait photographer Richard Beard told his subjects to say “prunes” as a cue to keep their mouths prim, according to historian Robert Leggat.

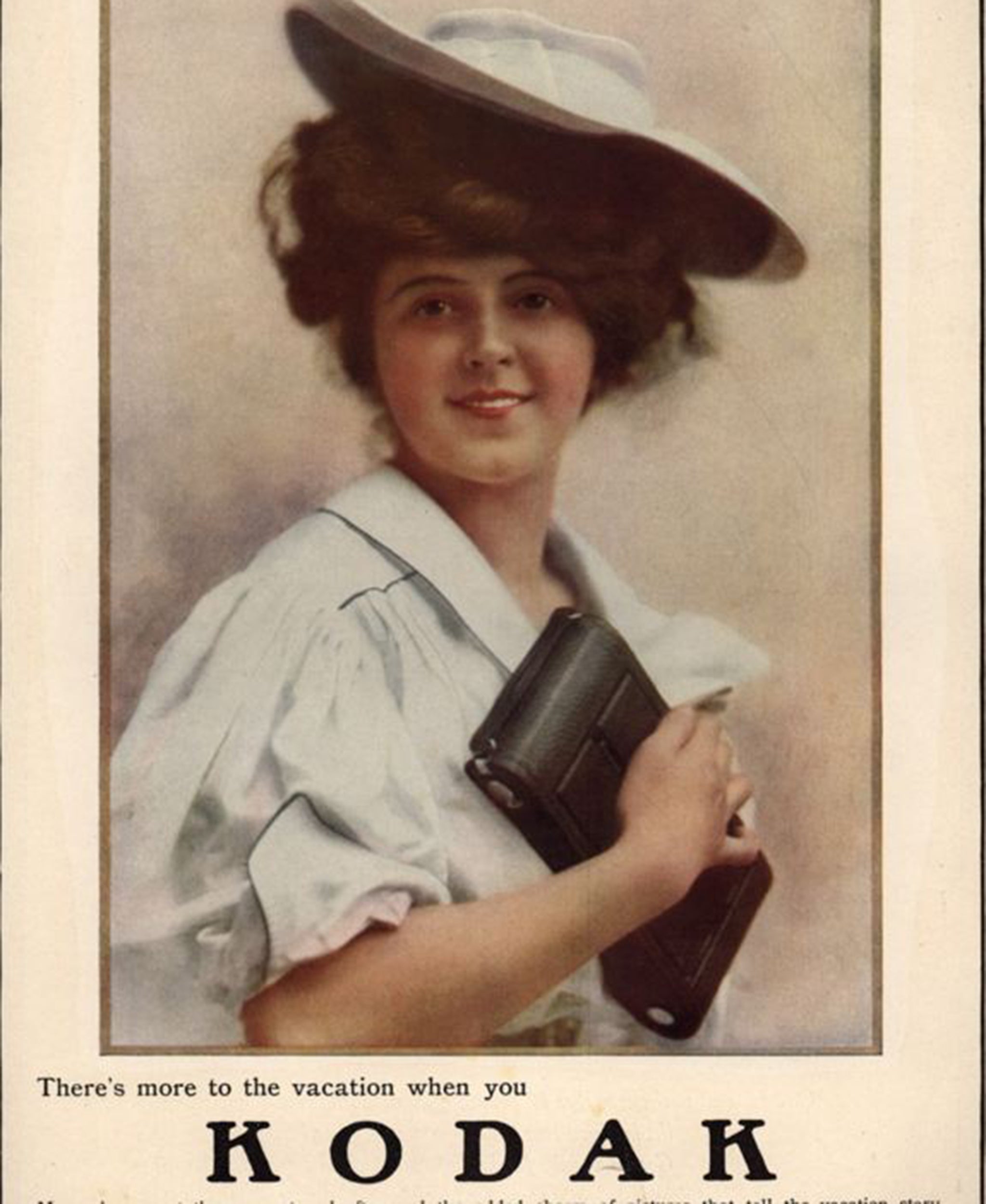

By the turn of the century, sitting for a photo was becoming affordable for average Americans, but the experience remained somewhat awkward. Eastman Kodak, the camera and film company that had near monopoly power in the market, sought to boost sales of photography to the middle class by making the process seem fun.

“Not surprisingly, early amateur portraits published in Studio Light [one of Kodak’s photography magazines] showed a sense of unease and fright before the camera,” Kotchemidova writes. “This nervousness had to be overcome if photography was to become popular. Kodak set out to mastermind the process.”

Kodak’s extensive marketing campaigns emphasised the pleasure of the photograph, instructing professional photographers to seek out families during holidays to strengthen the connection between celebrations and photography. And as consumers started to buy cameras for their own use, slogans like “Save your happy moments with a Kodak” taught them that the camera was a tool to record joy.

One ad from 1908 shows a woman with a beaming white smile holding her Kodak camera. "More pleasure at the moment," the caption reads, "and afterward the added charm of pictures that tell the vacation story." Another ad shows a smiling woman standing in a field of wildflowers, with the caption "Kodak as you go."

The photographic smile, Kotchemidova argues, was a byproduct of an increasingly sophisticated advertising culture focused on telling cheerful stories about products. By the 1920s, companies were using pictures of smiling models to sell everything from canned vegetables to cars. Employing the same visual language to sell cameras, Kodak and others had — in a very meta way — installed the smile as one of the "standards for a good snapshot.”

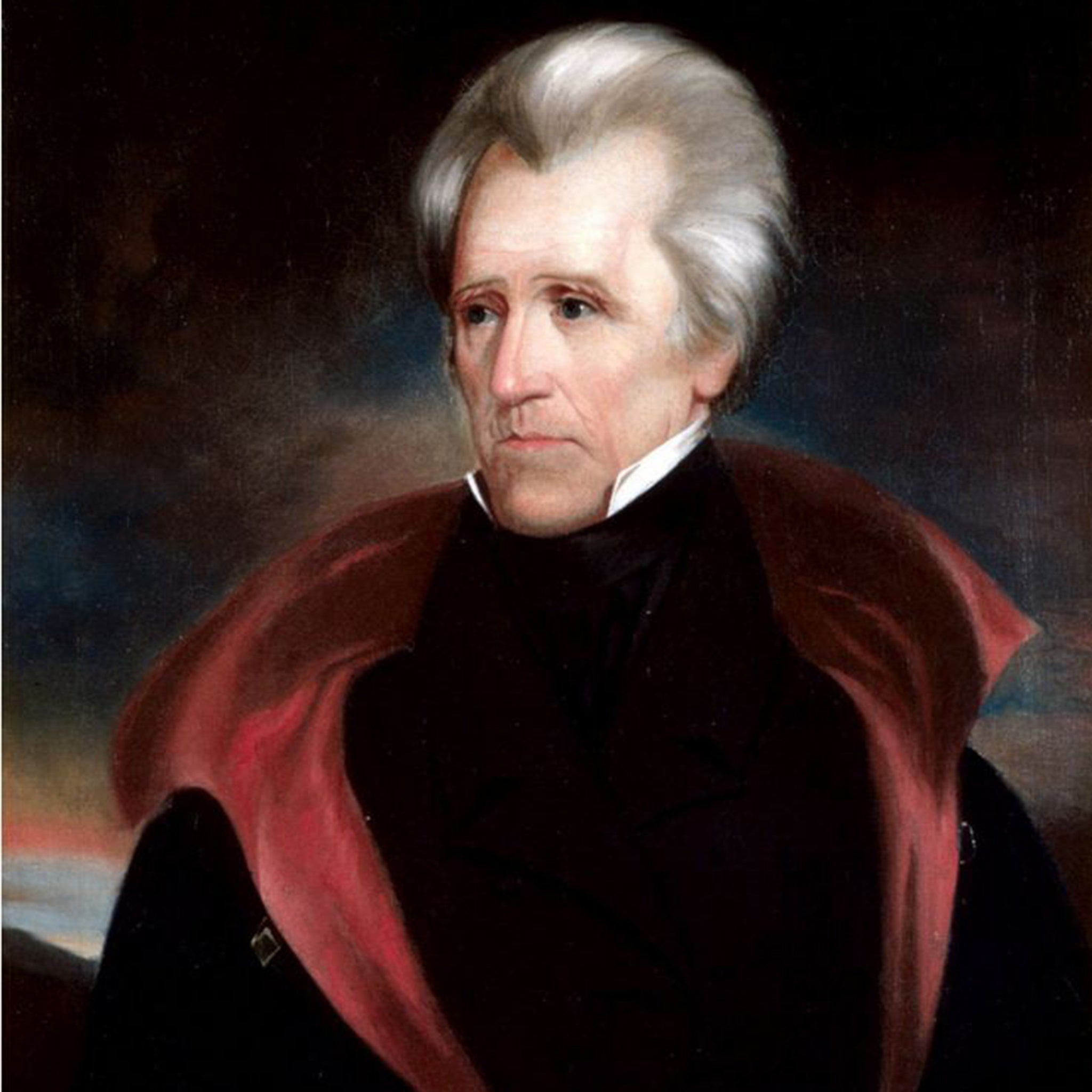

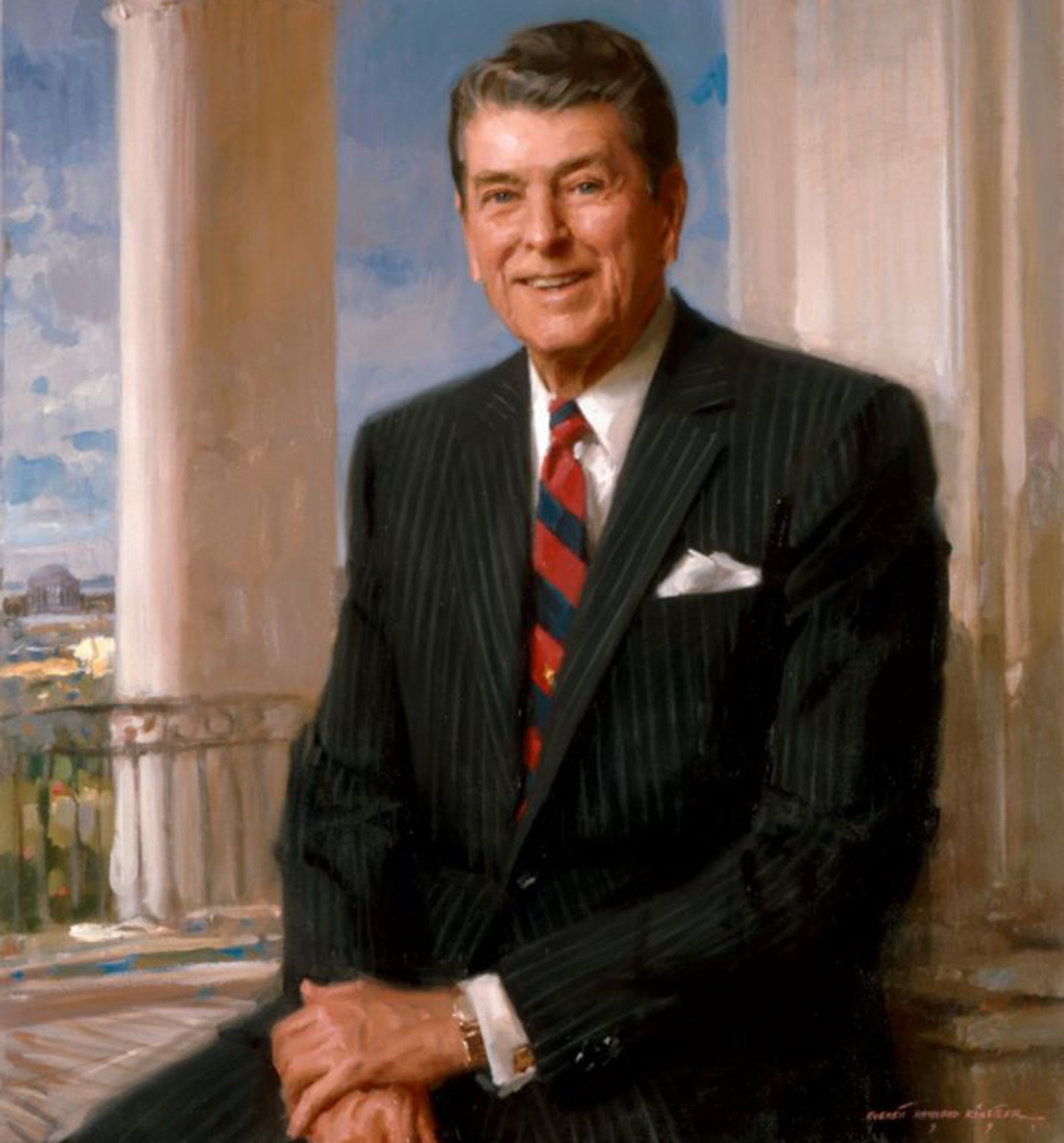

Snapshots, of course, are not the same thing as formal portraits, but official images have also become infected with good cheer over time. There are the yearbook photos from the Berkeley and Brown study, which show a progression from Mona Lisa smirks to full grins in the span of several decades. By the 1950s, even presidents were smiling in their portraits. The official painting of Harry Truman is distinctively friendly-faced, and Reagan’s expression borders on radiant. James Madison, in contrast, looked peeved, and Andrew Jackson seemed downright distraught.

The yearbook data suggests the photographic smile continues to spread — aided perhaps, by the popularisation of dental braces. With their glossy photographs, orthodontics ads illustrate that one of the chief pleasures of a perfect smile is the ability to say cheese with confidence.

Today, we mock portraits that look too intense or self-serious or vain. It's hard to imagine that a century ago, what many people found ridiculous was the smile.

In her 1913 book on Mark Twain, University of Chicago professor Elizabeth Wallace recalls walking with him when a fan approached him for a snapshot on the street. “I had noticed that Mr. Clemens always assumed a dignified pose at such times, with a serious, almost severe expression of face,” she wrote.

Twain responded with a quip that has now become famous. “I think a photograph is a most important document, and there is nothing more damning to go down to posterity than a silly, foolish smile caught and fixed forever,” he said.

Copyright: Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments