£100,000 appeal to save William Hoare portrait of freed slave

Support truly

independent journalism

Our mission is to deliver unbiased, fact-based reporting that holds power to account and exposes the truth.

Whether $5 or $50, every contribution counts.

Support us to deliver journalism without an agenda.

Louise Thomas

Editor

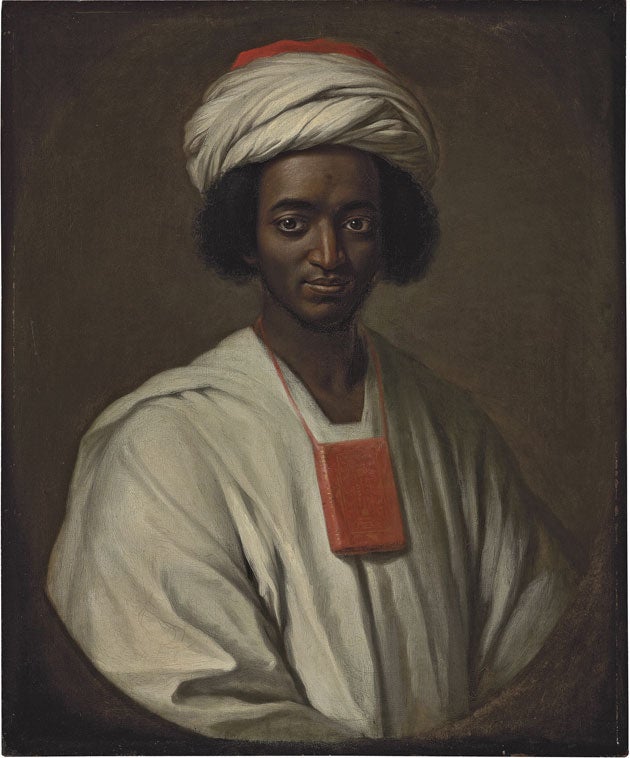

A campaign has been launched to save the earliest known painting of a freed African slave from being taken out of the country.

William Hoare’s early eighteenth century portrait of Ayuba Suleiman Diallo, a Gambian prince who was sold into slavery and later freed, was seen in public for the first time in more than a century when it came up for auction in December.

It was bought by a private collector for more than £500,000 but when the new owner applied to take it out of the country, the painting was temporarily stopped from being exported because of its importance.

The National Portrait Gallery has since been given until late August to raise enough money to acquire the oil painting and needs to £100,000 in donations from the public. The Art Fund has already donated £100,000 and the Heritage Lottery Fund has given a further £333,000. The rest of the money needs to be met by private donations if it is to remain in the UK.

The painting, which had been in the private collection of a single family since the 1840s, is highly unusual because of the unique circumstances in which it was commissioned.

Until it came up for auction last year historians were only aware of its existence through an engraving which had been based on the work and used in a book.

It is also thought to be the only eighteenth century English portrait showing a black individual not in some form of servitude. Equivalent paintings of the era tend to show black people as pages, servants or the exotica of rich patrons.

Lucy Peltz, the National Portrait Gallery’s 18th Century Curator, said: “It’s a truly remarkable piece of work. As a positive portrayal of a black person it predates anything we had previously seen by more than 100 years.”

Until the emergence of Hoare’s portrait, Benjamin Haydon’s 1840 depiction of the first Anti-Slavery Conference, featuring freed slave Henry Beckford in the front row, was thought to be the first time a British artist had painted a freed slave in a positive light.

Diallo was one of the few people to successfully escape the slave trade and return to his homeland. Born into a powerful family of Muslim clerics in the Senegambia region of West Africa, Diallo found himself sold into slavery when he was attacked by a rival tribe.

At the time of the attack Diallo had himself been on a trade mission to sell his own slaves and buy paper. He was transported on a British ship to Maryland and put to work on a tobacco plantation.

Following an attempted escape which landed him in prison, he came across the English lawyer Thomas Bluett, an early Christian evangelical who was impressed by Diallo’s faith and his high birth.

Concluding that the Gambian prince was “no common slave” he arranged for him to be released from prison and brought to the UK where he quickly made friends with many educated thinkers who would go on to inspire the anti-slavery movement.

His circle of evangelical friends were astonished by his ability to write out the entire Qur’an from memory and Diallo was known to have helped Sir Hans Sloane make English translations of the Muslim holy book. Hoare’s portrait shows the young prince with one of his own hand written Qur’ans strung around his neck.

Zeinab Badawi, the BBC broadcaster and a National Portrait Gallery trustee, said the painting helped provide further context to the narrative of both the slave trade and Islam in Britain.

"It is striking and important because Diallo is clearly a free, educated and well-heeled individual which makes such a strong contrast to the more common depictions at this time of Africans being in servitude,” she said. "What's more, the portrait features Diallo with a Qur’an around his neck - thereby reminding us that Muslims have been in Britain for many centuries.”

Getting the young prince to agree to having his portrait done was no easy feat because of Diallo’s Islamic concerns over idol worship. In his memoirs Bluett wrote: “[His] Aversion to Pictures of all Sorts, was exceeding great; insomuch, that it was with great Difficulty that he could be brought to sit for his own. We assured him that we never worshipped any Picture, and that we wanted his for no other End but to keep us in mind of him.”

Diallo spent just over a year in London but returned to West Africa after his freedom was obtained through a public subscription.

He continued to trade in slaves but struck a deal with the Royal African Company to broker the freedom of any Muslim slaves who fell into their hands. It took another one hundred years from when Diallo sat down for Hoare’s painting for both slavery and the slave trade to be abolished across the British Empire.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments