David Bowie: How I exposed the pop star's fake artist

Bowie helped create a fictitious Abstract Expressionist and convince the art world he was real – until David Lister, unmasked the deception

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It was one of the smartest tricks ever played on the worlds of art, literature and the media. It even involved the late David Bowie in one of his most mischievous moments.

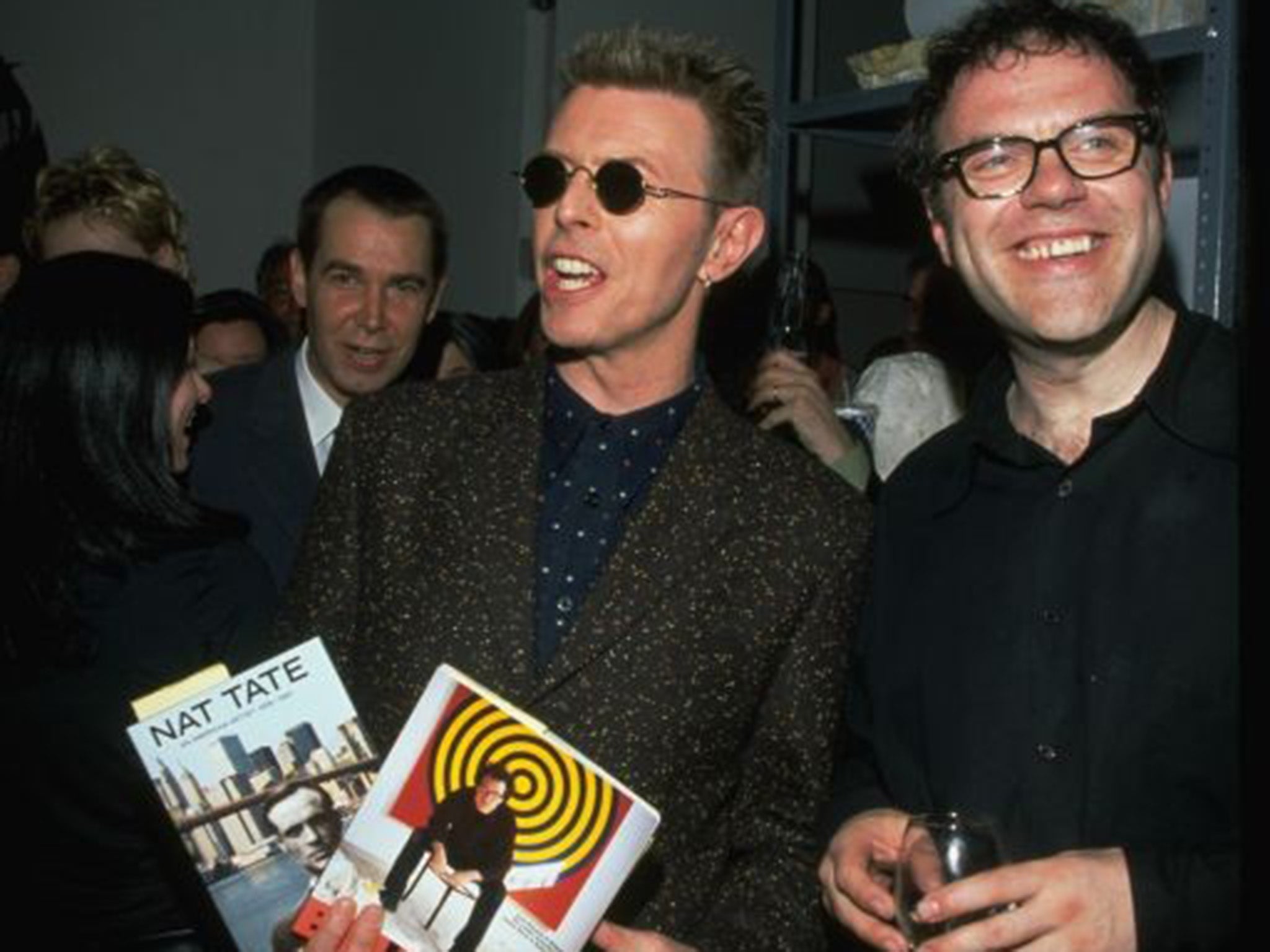

Among the many memories that the superstar’s death brought back for me was of one sultry evening in New York in 1998. Bowie, with his wife Iman at his side, hosted a reception in the studio of American artist Jeff Koons on the corner of Broadway and East Houston Street for the launch of the latest book by bestselling British writer William Boyd. The book told the life story of American Abstract Expressionist artist Nat Tate, who suffered from depression, destroyed 99 per cent of his work, and tragically ended his life by jumping from the Staten Island ferry.

Among guests at the launch were artists Frank Stella and Julian Schnabel, the hip New York novelist Jay McInerney, fellow writers Paul Auster and Siri Hustvedt, dealers, collectors, press and TV, and assorted hangers-on.

Bowie read from the page where Boyd heart-rendingly detailed Tate’s death leap at the age of 31. His body was never found and very little of his work survives. The gathering stopped sipping the whisky provided by the event’s sponsors for a few moments (Bowie at the time only drank water and sent an assistant to get some). The crowd took their eyes off Koons’s colourful, kitsch sculptures of kittens, and listened attentively, then resumed drinking, networking and seeing who could impress most with opinions about Nat Tate’s life and work.

It was a glittering evening, probably the major event in that year’s cultural calendar, and beneath the glitz a poignant tribute to one of the 20th century’s pioneering artists. More parochially, it was also the evening that was to give me the biggest scoop of my journalistic career. For, as I revealed on the front page of The Independent a few days later in an exclusive that was to go round the world, Nat Tate never existed.

The book, the artist, the party and the involvement of Bowie, who was certainly in on it, were all part of an elaborate, star-studded hoax. The book Nat Tate: An American Artist 1928-1960 was the first to be released under the imprint of Bowie’s new publishing venture, called 21. The project would certainly have appealed to his love of fantasy, acting a role, creating a persona, and indulging in sheer mischief.

I went to New York to cover the event and freely admit that as I travelled there on the plane I saw no reason to doubt the existence of Nat Tate. I, like all the rest, began to convince myself that I must have seen some of his haunting Abstract Expressionist works in one of our major galleries.

But once in New York, I began to have doubts. It was all very odd. This clearly was a major event. The Sunday Telegraph was running an extract from the book that weekend and The Observer was writing a report of the launch. Yet art lovers seemed only to have a passing acquaintance with the brief, sad history of Nat Tate, depressive genius, lover of Peggy Guggenheim, friend of Braque and Picasso.

Once in my New York hotel, I overheard some enigmatic conversations about Tate among the launch’s organisers and then reread Boyd’s short book. I decided to check out some of the detail in it. I went to inquire about Tate’s life at Alice Singer’s 57th Street gallery where Boyd wrote that he had first seen one of Tate’s drawings. 57th Street indeed existed. Alice Singer’s gallery did not. Nor did any of the other galleries referred to in the book.

I did a lot of walking in what was a mini-heatwave and found that address after address just wasn’t there. I then questioned some of those close to the project and the alarmed looks all but signed off the story for me. I also began to wonder about the name Nat Tate. How conveniently similar it was to one, if not two, famous London art galleries. It was all a brilliant ruse, more than helped by expert endorsements. Picasso’s biographer, John Richardson, was clearly one of the very few in on the secret, as was Gore Vidal, who described the book on the jacket as “a moving account of an artist too well understood by his time”.

Bowie himself very nearly went too far in writing on the jacket that “William Boyd’s description of Tate’s working procedure is so vivid that it convinces me that the small oil I picked up on Prince Street, New York, in the late Sixties must indeed be one of the lost Third Panel Triptychs. The great sadness of this quiet and moving monograph is that the artist’s most profound dread – that God will make you an artist but only a mediocre artist – did not in retrospect apply to Nat Tate.”

Neither Jeff Koons, who hosted the launch (held not insignificantly on the eve of April Fool’s Day), nor his fellow New York artists present were aware of the truth, or of the fact that at least one of the paintings in the book ascribed to Tate was by William Boyd himself. Photographs ostensibly of Tate were pictures taken by Boyd in various locations in the city.

So what did it all prove? Aside from the fun aspect, and the cleverness of Boyd’s use of and allusions to so many aspects of 20th century art, it showed, as his imaginative and brilliantly executed project probably intended, that the art world, perhaps the whole cultural world, is scared ever to admit to a lack of knowledge, scared ever to use the words: “I’ve never heard of him.” How quickly the great and the good of that world convinced themselves of Nat Tate’s existence. That’s something we could still all do well to ruminate on.

As I wrote at the time, “The critics, artists and gallery owners who have been taken in by one of the best literary scams in years must be wishing they could disappear as effectively as Nat Tate – and, like him, resurface with their reputations dramatically enhanced.”

William Boyd’s objective in writing the book was an intriguing and sophisticated one. Looking back, he has said: “My aim was, first of all, to prove how powerful and credible a pure fiction could be and, at the same time, to try to create a kind of modern fable about the art world. In 1998 we were at the height of the Young British Artists’ delirium. The air was full of Hirst and Emin, Lucas, Hume, Chapman, Harvey, Ofili, Quinn and Turk. My own feeling, was that some of these artists – who were never out of the media and who were achieving record prices for their artworks – were, to put it bluntly, not very good.

“However, there was a kind of feeding frenzy going on, an art-driven South Sea Bubble or Tulip Fever, and the story of Nat Tate in this context was meant to be exemplary. What is it like to be a very average artist who achieves great fame and wealth? What is it like when, as David Bowie stated in his blurb to the biography, God has chosen to make you an artist but only a mediocre one? This is Nat’s unhappy fate and it’s only when he is confronted with true artistic genius (in the shape of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque) that he finds the knowledge of his own single inadequacy too much to bear. He collects as much of his work as he can find and burns it. A few days later, in a fit of despair, he jumps off the Staten Island ferry as it crosses the Hudson River and drowns.”

And yes, the parable or satire was certainly well-timed. And the saga seemed to run and run. In 2011 a drawing signed by Nat Tate sold at Sotheby’s. It was, of course, by William Boyd.

And still the oddities surrounding the saga continue. For the first time yesterday I looked at the Wikipedia entry for Nat Tate and found that my part in it was duly recorded, but so was the conclusion apparently drawn by Newsweek magazine in New York that I too did not and do not exist. I’ll be sure to avoid the Staten Island ferry.

Journalistically, the story certainly made waves, being recycled at the time in papers as far away as the Andes. Not everyone thought it funny. William Boyd has since said that he was far from happy, as there was a UK launch of the book the following week in London, and The Independent’s scoop had rather changed the tone of it.

I suspect that David Bowie was rather more amused. Indeed, at the New York launch, I kept my eyes on him during the reading, and if I needed any confirmation that my story was correct, it was his constant smile and twinkle in his eye, even while reading aloud about Tate’s tragic end. Nat Tate could not have had a more illustrious, nor more appropriate, champion.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments