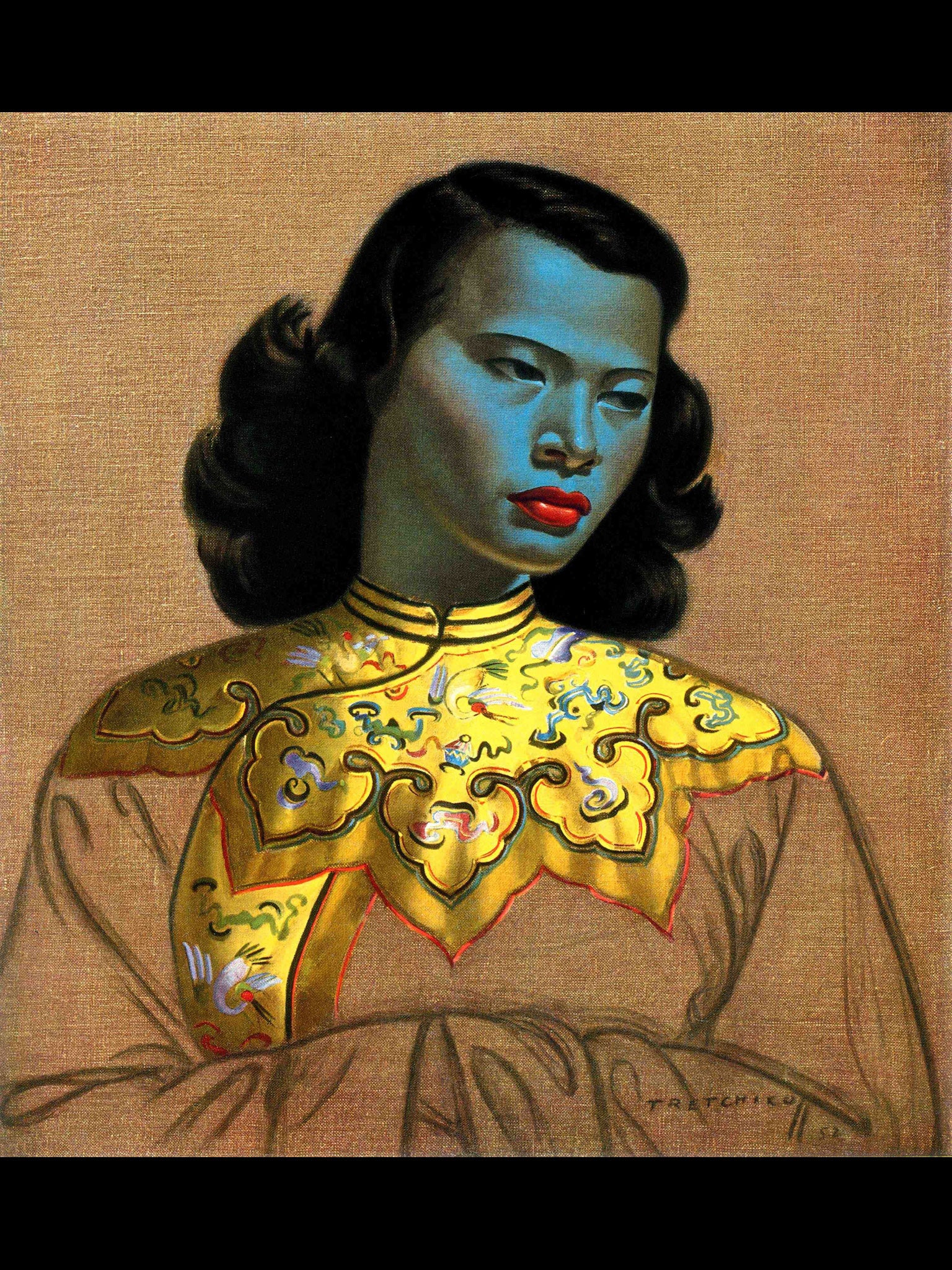

'Chinese Girl': The Mona Lisa of kitsch

There are millions of cheap copies of this much mocked lady all over the world, but the original is expected to raise £500,000 at auction this week. Matthew Bell tells her colourful story

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.With her copper green face and unfinished background, The Chinese Girl was never an obvious masterpiece. But cheap copies of this obscure portrait by a Russian artist were once so popular that it became one of the best-selling prints of all time.

Now, the original painting by Vladimir Tretchikoff, painted in 1951, is to be sold at auction in London. It is the first time it has come to the market since it was bought by Mignon Buehler, the teenage daughter of a businessman, at an exhibition at Marshall Field's department store in Chicago. In 1954, she paid $2,000; on Wednesday, Bonhams expects it to fetch up to half a million pounds.

The stories of the painting and its mass-produced copies couldn't be more different. After Buehler bought it, The Chinese Girl hung in her dining room for 20 years. In the 1970s, she gave it to her daughter, who took it with her wherever she lived. Her flatmates hated it so much they banned her from hanging it in the sitting room, and forced her to keep it in her bedroom. When her Arizona home was twice burgled, the intruders gave the same assessment both times, tiptoeing straight past.

Across the Atlantic, meanwhile, the work had a much better reception: Woolworths-framed prints sold in their millions, often to be hung next to the flying ducks of suburbia. Because the print was never sold in America, Buehler remained unaware of its popularity, but in the UK, Australia, Canada and South Africa, it became an icon of kitsch, and has featured in books on retro art.

Vladimir Tretchikoff's life was equally colourful. Born in Moscow in 1913, he claimed to be descended from Siberian landowners, ruined by the Russian revolution. Aged 19, he and his brother, Constantine, set off for Paris to attend art school; but they ran out of money, and Vladimir wound up in Shanghai. There he married a Russian émigré, Natalie Telpregoff, and they moved to Singapore, where he worked in advertising.

His colourful paintings went down well with the colonial set, and, in 1938, Tretchikoff represented Malaya at the New York World's Fair, hanging alongside the Bloomsbury artist Duncan Grant. When the Japanese attacked Singapore in 1941, his wife and daughter fled to South Africa, while Tretchikoff stayed on, instantly embarking on an affair with one of his models.

Tretchikoff eventually joined his wife and daughter in 1946, but not before spending three months adrift in the Java Sea, having been aboard the torpedoed HMS Giang Bee. Once established in Cape Town, he set out to make his fortune in commercial art. His fascination with exotic-looking young girls continued, and he would scout for suitable models near his studio. One of these was Monika Pon, who worked at her uncle's launderette, near Tretchikoff's home. Being young, half-Chinese and half-French, she was ideal. She sat for almost two weeks, and still lives in Cape Town today. She recently said she was paid the equivalent of £6 for her work. "I was so stupid, so young. What did I know about business?"

Tretchikoff included her portrait in an exhibition the following year in Durban, which caught the eye of some visiting Rosicrucians, who invited him to exhibit in their gallery in San Diego. In a bizarre twist, just before Tretchikoff left for America in 1953, someone broke into his storeroom and slashed a dozen of his works. In his autobiography, Tretchikoff claimed that The Chinese Girl had been among them, and that he had painted it again on arrival in America. But research conducted by Boris Gorelik for a new biography of Tretchikoff, to be published here this summer, suggests the American work was in fact the original.

"I looked through reports of the slashing of the paintings in Durban newspapers from the time, and they give a complete list of the paintings that were slashed. The Chinese Girl wasn't among them." Why Tretchikoff would later claim it was is unknown. The motive for the slashing also remains a mystery, and the perpetrator was never found: a set designer who worked in the same block of studios was arrested, and Tretchikoff claimed he had been jealous of his invitation to America. But the man was later acquitted.

Though Tretchikoff was always determined to enjoy commercial success, he could never correctly predict which of his pictures would sell. "He was a great marketer," says Gorelik. "He used to publish full-page adverts in daily newspapers, of one of his paintings, predicting that would be the best seller. But it was always other pictures that became popular." Those that did made him a lot of money, and he has been called the richest artist after Picasso, though Gorelik doubts that. "He certainly made money, and lived in a mansion in Bishopscourt, the most prestigious suburb of Cape Town, which he called the house The Chinese Girl built."

The first prints of The Chinese Girl became available in Britain in 1956, selling for £2 each, the equivalent of about £30 today. The question is, why were they so popular? "I think they matched people's expectations of the exotic," suggests Gorelik. "In the 1950s and '60s, people wanted to travel to foreign lands. Like rock musicians, who have a certain period when what they do matches popular taste – this is what happened with Tretchikoff. Somehow, he reflected their hopes and aspirations."

Not surprisingly, his work was never embraced by the art establishment. The critic William Feaver described The Chinese Girl as "arguably the most unpleasant work of art to be published in the 20th century". In his 2006 obituary of Tretchikoff, our own critic Charles Darwent called him "a painterly Barbara Cartland". Andy Warhol took a more populist view: "It has to be good," he said. "If it were bad, so many people wouldn't like it."

Even Gorelik, his biographer, admits to not being a fan, though he admires Tretchikoff's artistic honesty. "He painted what he liked. He didn't pander to certain tastes. There's a song by Big Audio Dynamite – former members of the Clash – called "The Green Lady", it captures the mystique that attracted people to him." His other lurid pictures also sold well, including Balinese Girl and Dying Swan. "You look at these women, and all the time they remain mysterious, you can't really analyse them. There's a certain – impregnability."

Tretchikoff remained in South Africa all his life, and is unknown in his native Russia. He became a minor celebrity, a tiny little man who drove a large pink Cadillac, which he often crashed. His enormous wealth and vulgar tastes probably did little to endear him to the artistic establishment –"I'd rather drive a Cadillac than ride a bicycle", he once said. But he called himself a Bohemian at heart. Tretchikoff dedicated his somewhat florid 1973 autobiography, Pigeon's Luck, to his wife, "who says that life with me is one moment heaven, the next hell, but mostly purgatory".

Now, Mrs Buehler's daughter has decided to sell the family heirloom. It is the star lot of Bonhams's South Africa Sale, to be held at their Bond Street saleroom. Speaking to Boris Gorelik recently, Mrs Buehler's explanation as to why she bought the picture probably chimes with that of many a Briton. "I thought it was lovely," she recalled. "I liked the combination of the Asian and the Western." Her daughter only discovered its fame by chance, watching television. "I saw it on some daytime TV drama. I said: 'Oh, my gosh! That's my painting!' I had no idea The Chinese Girl was famous."

Tretchikoff's value has risen enormously in recent years, thanks in part to the first major retrospective, held in South Africa in 2011. The current world record was set by the sale of a semi-nude portrait, Portrait of Lenka (Red Jacket), featuring Tretchikoff's lover from Singapore, which fetched £337,250. Whether The Chinese Girl can top that will become clear on Wednesday, but as to whether it's any good, who can say?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments