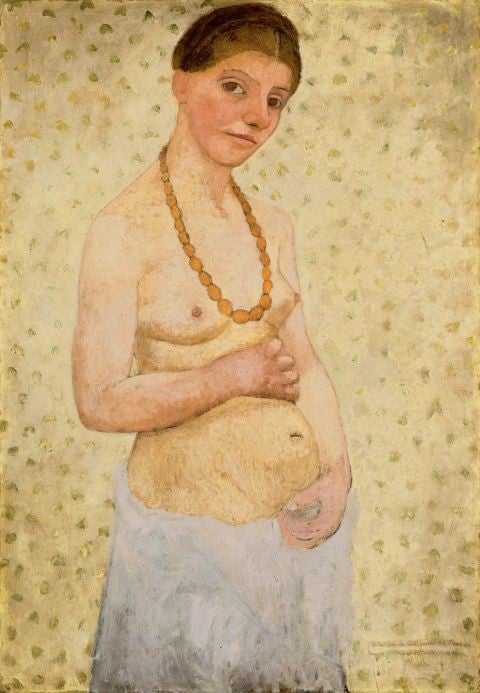

Modersohn-Becker, Paula: Self-Portrait on Her Sixth Wedding Anniversary (1906)

The Independent's Great Art series

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference. Also in this article:

About the artist

She stands there, naked to the waist, a young woman with big cow-brown eyes meeting the viewer's gaze. Her auburn hair is parted in the centre and swept up into a chignon, while her head is held on one side like that of a quizzical blackbird listening. Her eyes are level with those of the viewer, for the artist has portrayed herself life-size, as if painting her reflection in a mirror. Her smile is restrained and confident, yet knowing. A skirt of white cloth is tied loosely around her hips as she clutches her, apparently, pregnant stomach with raw, workman-like hands. Her right arm frames her upper body in a protective curve, while the left seems to protect her lower abdomen. Together they form an "S" that breaks the S-shaped stance of the otherwise static, slightly monumental pose. Around her neck she wears a necklace of lozenge-shaped yellow amber beads that glows warmly against her bare skin and falls between her breasts, close to her heart.

Her face has something of the land about it. The nose is broad, the cheeks rosy, the lips full and red. Yet for a pregnant woman, her breasts are still small and pert, the nipples and surrounding areola not darkened or swollen. The top of the cloth around her hips is level with her lower hand. Ethereal and white, yet with a tinge of blue, it is reminiscent of the loincloth that covers Christ in countless paintings of the Crucifixion, and seems to suggest some sort of spiritual sacrifice on the part of the artist.

The young German painter Paula Modersohn-Becker painted this, one of her most subtle and emotionally complex self-portraits, on the occasion of her sixth wedding anniversary, as she has written in olive-green paint in the lower right-hand corner of the canvas. She has signed it "PB", for Paula Becker, her maiden name, leaving out the Modersohn, which she had acquired on marriage.

Paula Modersohn-Becker was 30 when she painted this self-portrait on 25 May 1906. She had recently left her native Germany to live and work in Paris. What was extraordinary about this move was that, at the time, she was married to Otto Modersohn, an academic painter some 10 years her senior, whom she had met when she lived in an artist's colony at Worpswede, on the moors in northern Germany, near Bremen. There, her fellow-artists, encouraged by Julius Langbehn's eccentric and now notorious book, Rembrandt as Educator, along with their interest in Nietzsche, Zola, Rembrandt and Drer, idealistically embraced nature, the purity of youth and the simplicity of peasant life.

In Worpswede, Paula not only came under Modersohn's influence but also fell in love with the dark moors and the peasants who inhabited them, making their modest living from cutting peat. Yet she was soon to realise, rather like Nora in Ibsen's A Doll's House, that she had to break free of the shackles of conventional matrimony in order to develop as a serious painter. So, very unusually for a young, well-bred woman of that period, she abandoned her husband, much against his wishes, to go to Paris to paint. There she joined her close friend, the sculptor Clara Westhoff, with whom she shared a complex relationship with the German poet Rainer Maria Rilke.

This painting, then, is not simply a nude self-portrait but a declaration of liberation. Not only from the ties and duties of marriage, but also from the constraints and expectations of Paula's time and class. As she wrote in a letter to Rilke before leaving for Paris: "I am myself..." For she has painted herself as blooming and quietly exhalant, set against a dappled surround of spring leaf-green. Here she is her own woman, on the brink of fulfilling her true potential, at one with herself. When she arrived in Paris, she wrote: "Now I have left Otto Modersohn, I stand between my old life and my new one. What will happen in my new life? And how shall I develop in my new life? Everything must happen now."

In fact, Paula was not pregnant in this painting. Only the previous month she had written that she did not want to have a child yet, particularly with Otto. The painting, then, is a metaphor for how she felt about herself as a young artist: fecund, ripe, able for the first time in her life to create and paint freely in the manner that she wished. What she is about to give birth to is not a child but her mature, independent, artistic self. Traditionally, nude portraits of women had been painted for the delectation of the male gaze, but here Paula creates a new construct: a woman who is able to nurture herself outside the trappings of marriage, who does not need a man to be fulfilled.

For there had always been an unequal relationship between the male painter (however radical and avant-garde) and his model and muse. Women were sex objects, and models were purchased in a financial exchange that, by definition, privileged the male painter. In this portrait, Modersohn-Becker confounded this norm simply by painting herself.

Her nudity is confident and unabashed. Implicit is a level of self- awareness, for Paula would not have been unfamiliar with the debates about the unconscious that were raging in Vienna around Freud, and beginning to infiltrate both art and literature. The solid monumentality of the pose, the flattened forms and stripping away of detail indicate her awareness of both Gauguin and Czanne, whose work she discovered in Paris between 1899 and 1906. Both of these artists had a huge effect on their peers. The mask-like features and Paula's easy, natural sexuality show not only a familiarity with their work but also an awareness of the "primitive" art that had so inspired them and other painters of the time, from Nolde to Picasso. She stands there in her amber necklace, just as Gauguin might have portrayed one of his Tahitian girls garlanded with tropical flowers. For, like Gauguin, she was seeking the expression of some primordial power in the natural world.

Yet, for Paula Modersohn-Becker, in this self-portrait and its companion painting, Self-Portrait with Amber Necklace (1906), there is no subtext of violence or the sexual exploitation and appropriation that can be read into some of Gauguin's colonised Tahitian nudes with their blank expressions or downcast eyes. What she portrays is the solid dignity of the earth-mother, the liberated woman painted with a direct and fearless gaze.

She gives birth to the expression of her new fearless, artistic self. She was among the very first women painters to explore these concerns. That she collapsed with an embolism and died just weeks after the birth of her daughter, a mere year later, in 1907, gives the painting a haunting poignancy.

Born in Dresden in 1876, Paula Modersohn-Becker was 12 when her family moved to Bremen. In 1892, she received her first drawing instruction, and a year later came to England to learn English. In 1877, she saw an exhibition at Bremen's Kunsthalle by the members of the "Worpsweders" commune, artists who lived on the moors outside Bremen and took the French Barbizon school as their model, rejecting city life.

In 1896, she studied at the Society of Berlin Women Artists. She became close friends with the poet Rainer Maria Rilke, but married Otto Modersohn and settled in Worpswede. She later left him to live and work in Paris, where she immersed herself in French art. A reconciliation of sorts led her back to Worpswede, where, in 1907, aged 31, she died of an embolism after the birth of her daughter.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments