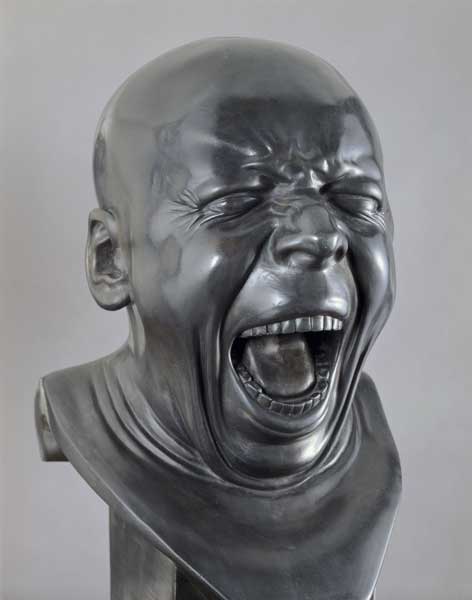

Great Works: The Yawner(c. 1770), Franz Xaver Messerschmidt

Szepmuveszeti Museum, Budapest

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Hugh Selwyn Mauberley, the hero of Ezra Pound's great poem of the same name, was said by his creator to be "out of key with his times". This has often been the case with writers and artists. They do not seem quite to fit into the world into which they are born. Consequently they are ignored or vilified. Such a person was the 18th-century sculptor Franz Xaver Messerschmidt, who was born in Swabia in 1736, nephew to the celebrated Rococo sculptor Johann Baptist Straub. All seemed set fair for the young man: his early works are made in a high Baroque style of a kind to please aristocratic and courtly patrons. And then, much later in his life, he began to make works which showed an alarming tendency to please no one but himself, and it is for this reason that they not only remained unsaleable, but were lost to view until long after his death.

Messerschmidt grew up in a world when the conventions of the portrait bust were fixed and solid. Their aim was to elevate and aggrandise the subject, to offer up a harmoniously idealised version of the truth for the delectation of the patron who wished to be pleased and flattered. In the last decade of his life, Messerschmidt revolted mightily against these conventions for reasons known only to himself. He began to make busts such as The Yawner, which are the flagrant opposite of idealised representations, violent distortions of the same – it is as if they are in conflict with everything that the traditional portrait bust represents. They look like quirkishly aberrant psychological studies, rootings into the world of marginalised – if not mad – beings. Beings? Well, as far as we know, the only sitter was Messerschmidt himself, though of this we cannot be entirely sure.

There are about 60 of these busts in existence, and Messerschmidt made them all during the last decade of his life, when he was living a life of relative seclusion in Bratislava, miles away from the world of aristocratic and courtly favours in which he was once so accustomed to live as a gilded young artist. By this time his working habits were fitful, and he was often unwell. When he worked at all, he did so to please himself, to tease out a vision of the human head – there is almost never any hint of a torso and seldom a neck – unlike anything that would be made until the habitual distortions of the 20th century.

The Yawner, which is made from pewter, is a typical example of his manner. Call it satire of a particularly extreme kind if you like. The mouth yawns open in a terrible simulation of a scream – it is almost audible. We see right into the mouth cavity. We can examine the tongue and its underside, the lappings of flesh beneath it, the teeth. It is all utterly unseemly, if not grotesque. The chin is pushed down deep into the neck, creating thick, rubberised ripplings of flesh. The neck barely exists at all. The longer we look at it, the more we begin to understand that such extremes of contortion may not be possible at all – the head is thrust down, the eyes screwed impossibly tight, the mouth jammed as wide as possible, the nostrils pneumatically dilated. The crows' feet fan out from the corners of the eyes, the muscles bunch, clench horribly above the bridge of the nose. Is it really possible to do all these things simultaneously? Try it for yourself. I think not.

Now look at the treatment of the crown of the head. This too is fist-shakingly unconventional. For a start, there is no wig. In fact, Messerschmidt dispenses with wigs altogether in these portrait heads – a shockingly unconventional thing to do during these times, when it was of paramount importance to beautify the head with ever-more extravagant hair pieces. Messerschmidt has ripped away all this puffed and powdered decorative nonsense to reveal a smooth-domed skull decorated with delicate striations of marks – low-relief furrowings.

The unexpectedly wayward violence and sheer effrontery of it all quite takes the breath away – even today. This is a man's head quite out on its own, a man who bears no resemblance to social man at all. This is a man whose soul is out of sorts – at war – with his body. His contemporaries were horrified. Only late in the 20th century were these busts at last widely displayed, and the sheer oddity of Messerschmidt's wayward genius understood.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Franz Xaver Messerschmidt was born in Wiesensteig, Swabia, in 1736. He studied sculpture in Munich, and then moved to Vienna in 1755 to complete his academic training. Although he was greatly admired by the imperial family (he created several much admired busts, mounted on ornate pedestals, complete with lavish draperies of the imperial family, in a high Baroque manner) he failed to establish himself as an academician, and eventually retired to Bratislava, where he died in 1783, at the age of 47. His most celebrated works are in his series of Character Heads. Today these grimacing faces, so natural and so unnatural simultaneously, near-perfect representations of buffoonery, shock, and dismay, intrigue the onlooker.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments