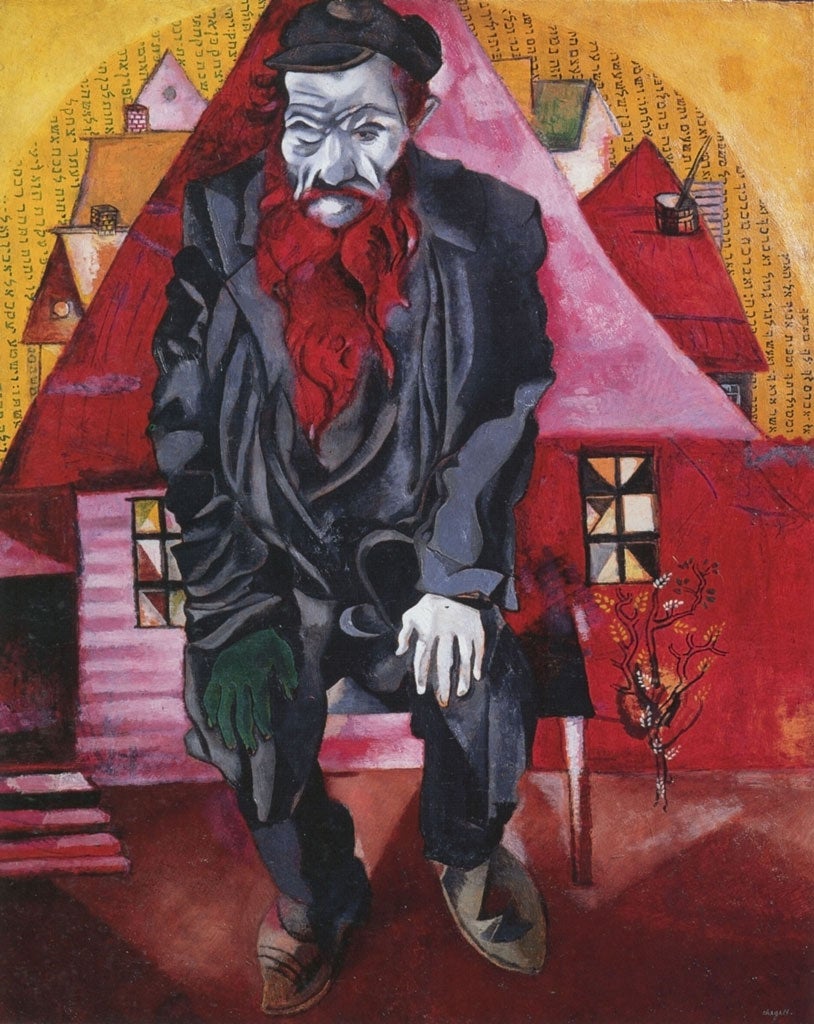

Great Works: The Red Jew, 1914-15 (100cm x 80.5cm) by Marc Chagall

Russian Museum, St Petersburg

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Marc Chagall returned to his home town of Vitebsk from Paris in 1914, and there he remained until the following year, painting obsessively – street scenes, the members of his own family, and an entire series of old Jewish beggars, often rendered in the most unpredictably brilliant slashings of colours.

These paintings – Jew in Bright Red, Jew in Green, The Praying Jew, for example – represent both a turning point in his art, and a radical reappraisal of the depiction of Jewish themes. The fantastical subject matter of his recent past has fallen away – yet, stylistically, he remains as daringly experimental as ever.

He is both rooted in the new of Cubism, Fauvism and much else, and yet he also feels redefined, refreshed, if not almost transfigured, by a subject matter that is both wholly traditional and wholly familiar to him from his earliest years. He is both inhabiting the past of his town, his race, his homeland, and simultaneously alive to the wonders of the artistic experimentation of Paris. To return is to see the familiar anew. And there can have been few sights quite so familiar to him as the ragged, itinerant Jewish beggar that you can see on this page.

Here we have seated, slumped on a chair or bench in front of us, an old man, a wandering outcast, a very model of decrepitude, poverty and loneliness, and yet he is a figure who also appears to possess all the symbolic weight of his persecuted people. He is both shrunken-small and immense in his presence. His cap grazes the top of the painting. His feet, blushed by a medley of colours, rendered in a slightly proto-Cubist way, turn out slightly.

The arc of yellow that sweeps across the top of the painting and the red triangle of the roof against which he sits, seem to contain him within a sacred, niche-like space. He could be an emanation of the sun, were it not, given the broken and wearied look of him, slightly laughable to entertain such a preposterous thought. His beard spills like the flames of some all-consuming prophetic fire. His face is pulled askew.

Only one eye is open – which gives an added gravity to the quality of its seeing. It is both seeing the world, and seeing through the transience of the world. He is both a victim and a witness, an almost-nothing in so far as he is an impoverished beggar, and an everything too; a heavy, stolid, partially repulsive element of the here-and-now, and a near weightless symbol of holiness and merciless truth-telling.

At his hunched back an entire world seems to be in waiting: triangular roofscapes stack, receding away from us, partially floating; windows show off their fanciful triangles of colour. And among these common details of the town, religious symbolism inveigles itself: that vertical patterning of Hebraic characters; the pen and inkwell, which are suggestive of the passing down of rabbinical lore, and the enigmatic tree.

The fact that he is such a dominating presence here means that it is he alone who counts, who judges. Occasionally, Chagall needed to paint these subjects quickly, he once confessed. "Sometimes a man posed for me who had a face so tragic and old, but at the same time angelic. But I couldn't hold out more than half an hour... he stank too much."

About the artist: Marc Chagall (1887-1985)

Marc Chagall was born the son of a Jewish herring merchant, and escaped the "potato-coloured" Czarist Empire in 1911 to cultivate his talents amid the vibrant artistic circles of Paris. There is a marvellous weightlessness and a whimsical joy about much of his work. He found reasons to rejoice even as he lived out his own life in a world that was often war-torn and utterly joyless.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments