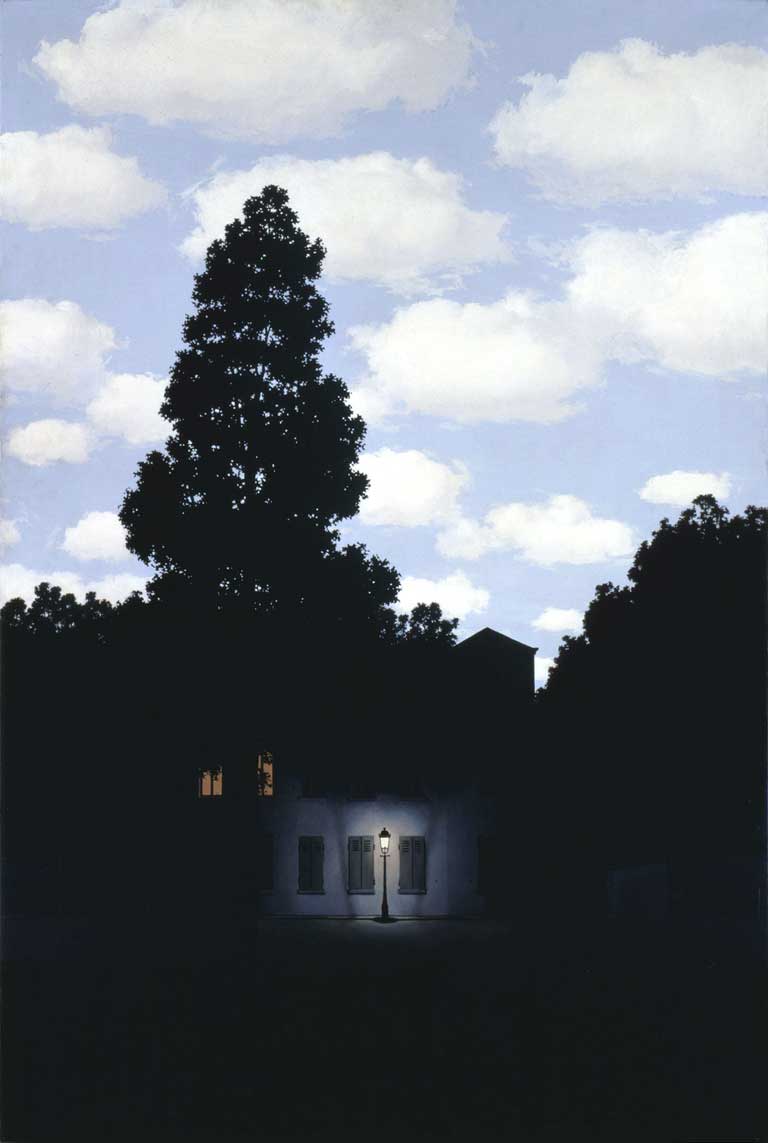

Great Works: The Dominion of Light, 1953-4, By René Magritte

Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Is there anything that can really surprise us about René Magritte? He has been too much with us for too long. His paintings are often just as good – if not better – in reproduction than they are in actuality. He is a one-trick wonder: once you have seen a painting, smiled at the gorgeous visual trickery of it all, there is nothing more to explore of him. You do not return to him again and again – as you would to the works of a truly great painter – and find new levels of meaning. What is more, he is not even that good a painter. He knows how to organise elements about a surface. He knows about the use of decorative effects. But he often paints hands very badly. What is more, the work feels more than a bit dated. We are all post-Freudians, aren't we?

And yet, from time to time, his paintings do genuinely resonate. Consider The Dominion of Light, for example. This is a theme that he explored again and again. In fact, he painted it 27 times in all, sometimes in oils and at other times in gouache; sometimes large, sometimes small. This particular version hangs in the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, and it used be displayed on a wall beside a great window that opened on to the Grand Canal and a marvellously flooding Venetian light. That positioning seemed to add to the rich and haunting ambiguities of the painting itself. Why did he paint so many versions though? To please his dealers? Only in part. He also did it in order to squeeze all the poetry that he could out of this delicious conceit.

We see the dark exterior of a house, with a single illuminated street lamp. But the sky is in broad daylight. Night and day are present simultaneously. This is unnerving, the simultaneity of daylight and darkness. It disturbs us visually and morally. Can light co-habit with darkness, good with evil? Well, yes, man is such a patchwork creature of light and dark, the will to do good, the propensity to choose evil. There is skylight, and then there is the artificial light of the gas lamp. That man-made light seems to enwrap us, secure us from danger. What is odd about the nature of the blackness that presses against the lamp is that it feels as if it could be a layer of blanketing warmth – protecting us against the flighty dangers of that cloudy and forever unruly dreamscape. And so we go on, mining the depths.

About the artist: René Magritte (1898-1967)

The paintings of the Belgian Surrealist René Magritte are simple, direct examples of what could be described as a kind of magic realism. Tonally lacking in subtlety, they make an immediate and disturbing impact. One of the difficulties with his manner of painting is that the work always feels just a little too calculated, as if these are not so much the making of paintings as the expression of ideas. The jokes, however, are undeniably good, and he remains immensely popular.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments