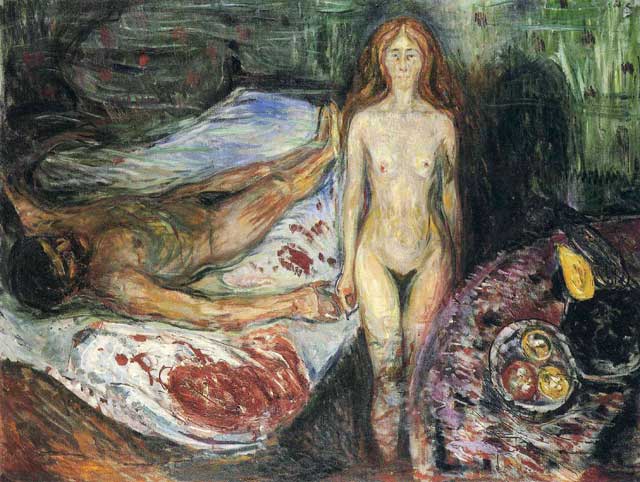

Great Works: The Death of Marat, 1907 (150x200cm) Edvard Munch

Munch Museet, Oslo

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The paintings of Edvard Munch often confine the onlooker within an unnervingly straitened psychological space. You are present, watching, but it also feels a little like eavesdropping – and a little like entrapment, too. This is especially so of Munch's self-portraits. Munch, like Rembrandt, was an obsessive, life-long self-portraitist, but the way in which these two artists approached the task could not have been more different. The essence of Rembrandt does not change from portrait to portrait – his sense of self was relatively stable. What changes is the costuming. Rembrandt is consistently faithful to the abundant world, which exists outside him with all its gorgeous, fleshy tactility.

With Munch, there is a terrible blurring, if not a smearing, between inner and outer worlds. He is forever taking his own temperature. In a relatively early one, the Self-Portrait with a Burning Cigarette of 1895, he shows himself, though eerily lit, to be a debonair, raffish smoker, almost clubbable. Never again. Generally speaking, when Munch paints himself, he does so in order to prove that he exists, that he is still fully embodied. His portraits are nervy, febrile, tense in the extreme. He changes, and changes again. He seems to be present at a haunting – but the person doing the haunting, and the person who is being haunted, happen to be the very same man whose face he confronts in the mirror every wretched, workaday morning. His colours are often feverishly wild and unpredictable. They are faithful to nothing but the vision of Edvard Munch. The more intense the reds, the purples, the yellows, the worse things are going.

So what exactly is being enacted in this strange work? It shares its title with a celebrated painting of 1793 by the memorialist of the French Revolution, Jacques-Louis David, which showed the revolutionary leader, Jean-Paul Marat, dying in his bath. When David paints Marat dying, there is no sign of the murderess, Charlotte Corday.

In Munch's version, the malignant woman dominates the proceedings. What a wild state of affairs is conjured here! Look how it is painted, all this ferocious whirlpooling of brush strokes. The entire painting is like a kind of emotional maelstrom. Everything comes at us all at once, tipping and lurching, with great vividness and violence. The use of colour is almost anti-irrational – as if Munch is cocking a snook at the power of human reason to make sense of our terrible, howling complexities. The marks of the brush – horizontal, vertical and many points in between – are ferociously apparent across the painted surface, like some brutal ritual of scarification.

And yet throughout this wild evocation, the murderess seems to float towards us, almost ghost-like in her thin, pallid, unnerving, hour-glass-like beauty of sorts. She seems so strangely settled in her otherworldly indifference to her own crime. A huge, ominous shadow – of what? – hulks at her back, as if to suggest that much is not what it seems. The murdered man himself is like so much detritus – crude, puppet-like, and unlovingly flung to one side like a bloody, discarded mannequin.

Although Munch is pretending to distance the work from his autobiography by associating it with a key moment in the French Revolution, this is in fact a feint. He is referring to events in his own troubled life. The ghostly Charlotte resembles his sometime lover, Tulla Larsen. The blood that is smeared across the bed on which the murdered man lies is also rooted in the particular. Munch had shot himself in the finger after a row with Tulla in 1902. A certain amount of blood had flowed. His feverish imagination would never let him forget that act. Now we see it again, fully transfigured, and even sensationalised. As in so many paintings by Munch, he is also addressing the nature of the war between the sexes, the terrible, vampiric unpredictability of the feminine, so seductive, and yet so fear-inducing.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

The Norwegian painter Edvard Munch (1863-1944) is a conjuror of disturbing psychological states. He painted his famous work, 'The Scream' (1893), over and over again. He was not so much interested in painting reality, as in trying to discover the heightened visual equivalent of intense human feeling.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments