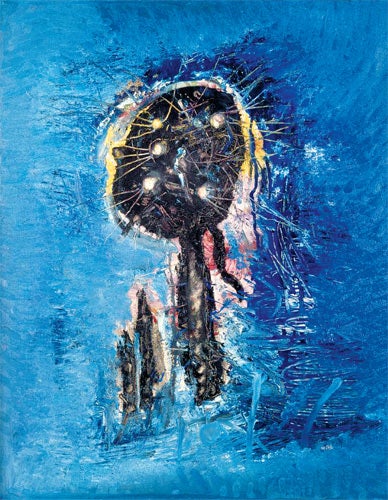

Great Works: The Blue Phantom 1951, Wols (73cm x 60 cm)

Ludwig Museum, Cologne

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In order to get to grips with this extraordinarily disturbing oil painting, made in war-pummelled post-war Europe, by a man who was born Alfred Otto Wolfgang Schulze and later came to be known (more conveniently) as Wols, we need to dig into the history of abstract painting a little. There are so many varieties, and the idea of abstraction has been championed by so many, and for such widely differing reasons. Abstraction has been said by some to universalise human experience, to lift us away from and beyond the disappointing contingencies of everyday life, to be dealing, in short, with the essences of things. The essence of matter. The essential energies of the universe. The spiritual heart of things.

This, of course, puts it in a commanding position from which to look down – from a great height – at all those messy figure painters who have been spending their days much less loftily. Abstract painters and those who choose to interpret them often make much of what the paintings are made from. When Jean Dubuffet's work is talked about, for example, we hear about sand, as if the work's meaning part-resides in its maker's choice of material. You don't have to dig too far into sand to find barrenness, for example. No harm in that, of course.

Let us be perfectly honest about this though, it is often very difficult to know quite what to talk about – or even what to be thinking about – when you are staring at an abstract painting. What it is made from – provided, of course, that the maker is not too secretive (and some are very secretive indeed) – is usually something that can be established quite incontrovertibly. But abstraction does throw up barriers. It can often feel quite emotionally chilly, as if it is not so much a local view of life as a kind of a grand summing up, to which we should all be paying urgent attention. When looking at it, you sometimes feel tempted to button up your coat against what you perceive to be emotionally inclement weather.

Certain branches of abstraction are severely geometrical, as if they are a sub-branch of a particularly abstruse form of mathematics. Not so this painting. The particular kind of abstraction with which Wols himself came to be associated was called Art Informel, and it leads abstraction off down a path which brings us closer to the breathingly human – but not too close.

We need to ask ourselves what extent this is an abstract painting at all. In part, surely, it is no such thing at all. Surely it is a childish representation of a human head and an attenuated human body, with that curious, squirming, pig-tail-like shape that drifts down from the bottom of the back of the head standing in for human hair. Or perhaps it is mid-way between a human and a plant form. All those spiky excrescences suggest the probing needles of cacti, for example. Or am I being too literal-minded here? No, I don't think so. You feel it, somehow, on the pulses, that this is a painting about the essence of the human, and about isolation, human isolation. The human element is not particularised, however. This is not little Harry fresh out of the shower. It is generalised. It is also alienated. The form, we feel, has risen up not from Surbiton but from the extreme outer limits of Elsewhere. And yet we cannot but feel that it is essentially human all the same, and that it is speaking to us – perhaps even wailing at us – out of its own pitifully impoverished humanity. Certain forms, when in relation to other forms, call meanings to mind, and this roughened ball on the end of what looks like the blasted stump of a tree calls to mind a human presence.

But to what extent is it grounded in its space? It appears to be emerging from its background, phantom-like, like a bad dream. The application of paint is violent and harried – criss-crossings; short, brutal down strokes; interlocking meshings and spikings. The paint seems to be at war with itself. It floats against – or out of – a variable blue ground. Blue for the limitlessness of the ocean, we idly speculate. Or could it the inexhaustible bluenesses of the endless skyways?

This strange lump of a form has risen up out of that space, and now presents itself to us, unflinchingly, for examination. And yet there is nothing readable here to be examined, not from a human point of view. We recoil in horror at what we see. If this is some kind of abstracted representation of the human form in crisis, lord God above what have we come to? Are we this close to the edge? Are we quite this estranged from ourselves? Is this what all our brutalising behaviour has brought us to? The form itself offers up no answer. Nor does it go away.

ABOUT THE ARTIST The German painter Alfred Otto Wolfgang Schulze (also known as Wols), who was born in 1913 and died in 1951, studied under Mies van der Rohe and Moholy-Nagy at the Dessau Bauhaus. He made images that seem to swim out from his troubled inner being. He moved to Paris in 1932, and later illustrated works by Kafka and Jean-Paul Sartre. Sartre, writing on him in 1963, described him as "human and Martian together... He applied himself to seeing the Earth with inhuman eyes: it is, he thinks, the only way of universalising our experience."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments