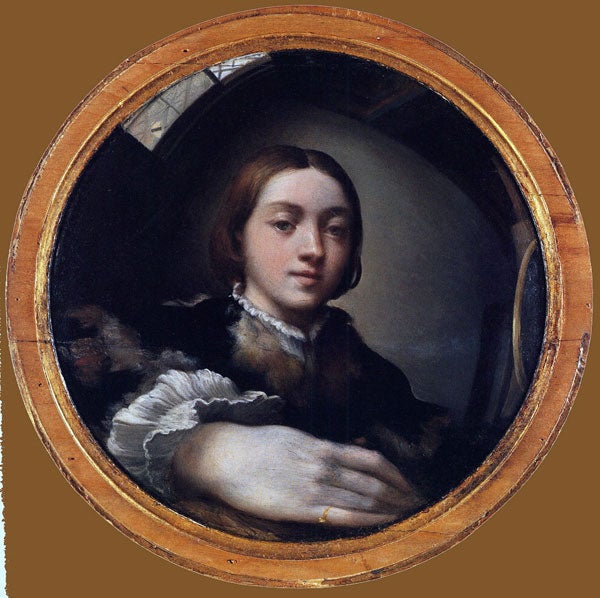

Great Works: Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror (1524), Parmigianino

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Since Brunelleschi created linear perspective early in the 15th century, thousands of painters have created the illusion of credible three-dimensional worlds into which we have all been invited to step. Some painters have found that depth of illusionism too shallow a challenge. They have wanted to persuade us that there are super-subtle tricks of painterly effect which make mere three-dimensional illusionism seem as easy as winking by comparison.

The Mannerist painter Parmigianino painted his Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror in 1524 when he was 21 years of age – in fact, he may have been slightly younger. It was thought by the great 16th-century biographer Vasari in the first version of his life of the painter, written about 30 years after Parmigianino's death, that it may have been painted as a gift for Pope Clement VII. Parmigianano made it, quite deliberately, as a bravura performance, to prove, at a stroke, his own brilliance, and Vasari duly waxed lyrical about its extraordinary qualities. This was not the only time that Parmigianio was to paint or to draw his own features. Like Rembrandt, he found his own image utterly absorbing. Unlike Rembrandt, however, Parmigianino died young – at the age of 37 – and so he was not able to chart the fascinating subject of the ageing of human flesh.

In the Self-Portrait, Parmigianino is very young – and he looks younger still – so young that he could almost be a prosperous child of aristocratic parents. Throughout his career he was fascinated by distortion – the way that a face or an arm, when it draws away from the eye, seems to elongate. How to take this fascination to such lengths that the viewer would be awe-struck?

Here is the conceit of the painting. Like Van Eyck in the Arnolfini portrait that hangs in London's National Gallery, Parmigianino was fascinated by the idea of the convex mirror, and the image that such a mirror throws back at the onlooker. According to Vasari, Parmigianino studied his own face in what Vasari describes as a "specchio da barbieri" and later arranged for a wood turner to make a ball of the appropriate size. He then halved it – and painted on it. But Vasari, as anyone who has examined the painting will have noticed, was not quite right. This cannot be true. The surface of the painting is shallower than he leads us to believe – though you would not know that from the image itself.

In the painting, which is quite small – its diameter is less than 25 centimetres – the young man is staring back at us with a look of unusually serene appraisal. He is a sweet-featured, almost strikingly beautiful young man, with chestnut-coloured hair divided down the middle, and he is richly dressed. The back of his hand, which curves towards us, is unusually prominent, and very large, exaggeratedly so. Why? Because it has been caught in the distorted glass of the convex mirror into which he is staring. We, the onlookers, are looking back at him. The painting is round, and set inside a sumptuous gilded frame. It is the likeness of a mirror. It is a mirror.

So this is the situation. We are looking as if at a mirror in which the artist himself is reflected. It is not an entirely flawless mirror. The image is overlaid by a slight haze, which helps to distance us from the young man. It is as if we are seeing his face in a dream, albeit a waking dream. He too is looking into a convex mirror, painting himself. This is why his hand is unusually curved and unusually prominent – because he is painting himself with his left hand – we see it as his right hand, of course.

It is slightly unusual that a painter who is so well dressed – his cuffs are surely of lace; his collar may be ermine – should be engaged in painting himself in this way. This perhaps explains his air of slight bemusement. The story – though the painter knows it not to be true because he is a complete virtuoso – is that he has taken it upon himself to do something that for him is slightly unusual, and the act upon which he is engaged is almost bewitching – hence the slightly rapt expression in his eyes. We cannot see the tool that he is using, but it seems evident that this is what he is doing. Why otherwise would he be appraising himself to this degree? Why else would his hand be raised at this angle if it were not in the throes of applying paint to surface?

It is as if then we are looking at a convex mirror, and in that mirror we see a young man looking into a convex mirror. The details of the room behind him are suitably distorted – the window bends like rubber, as does the coffered ceiling. And on the right hand side (from our perspective), we see a glowing panel. That is the reflected image of the painting which he is engaged in painting. That is the portrait of the artist in the convex mirror. That is the act of artistic creation to which we are being made privy thanks to the fact that we too are being allowed to stare into the very convex mirror that the artist himself is staring into. Can there ever have been a more ravishingly beautiful visual conundrum proposed by an artist in the Western tradition, so satisfying intellectually and visually?

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Born Girolamo Francesco Maria Mazzola, the Italian Mannerist painter and engraver Il Parmigianino (1503-40) was named after his birthplace, Parma. He painted many great church frescoes, but his greatest works are his portraits, which manage to be both warmly intimate and oddly estranging. He was influenced by Correggio, Raphael and Michelangelo.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments