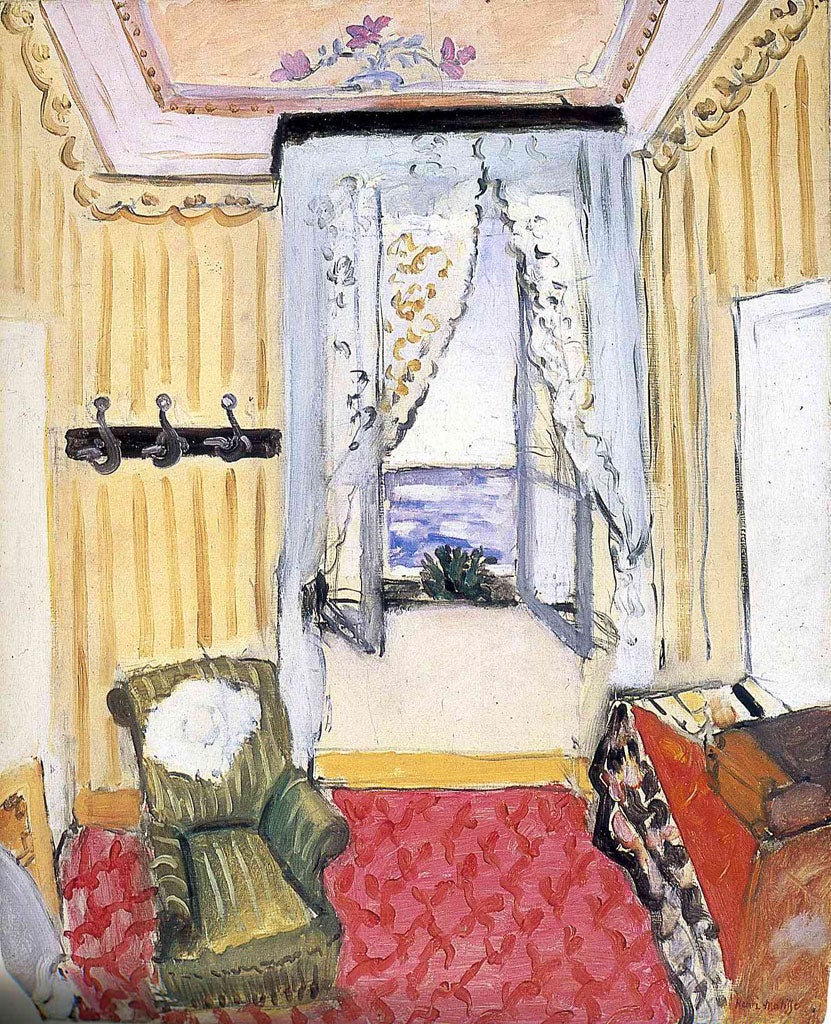

Great Works: My Room at the Beau-Rivage 1917-18 (73cm x 61cm) by Henri Matisse

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Pennsylvania

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Rooms as painted spaces, forms of stage-setting if you like. Sickert's rooms in Whitechapel, for example: dingy, dark, mildly urinous; depositories for heavy, blowsy, pneumatic flesh sprawled across beds; exuding an air of indefinite menace. Or Vuillard's rooms in France: fussily patterned, closing in on themselves, smaller than they probably were.

And what of Henri Matisse, that lover of rooms? So much of Matisse is about room-making, creating imaginative spaces within the severely constraining confines of four walls. What we see here is an art of pure fabrication – call it a confection if you like because it looks quite sweet to the tooth. There is triple framing here, which adds to a sense that this is to be a kind of understatedly pleasing visual fanfare. The picture frame frames the subject of the room. The room itself is a framing device. The window frames the sea. Matisse painted the various different rooms where he lived in the south of France over and over again. He was quite an itinerant in these years. They were not special rooms, and they were often quite sparsely furnished. All to the good, must have been his thinking. A neutral room such as a hotel room always happens to be can always be re-made in the image of its latest occupant.

Nothing dramatic is happening here, of course. That is not the point. In fact, nothing is happening at all. Visitors were often quite disappointed by the rooms themselves when they visited them after they had seen the painting. How could Matisse had made so much out of so humdrum little? Here we can see his suitcase and some canvases propped against the wall. Little else. So much of the rest is decorative effect, foreshortening, the rhythms of the carpet's patterning set against the stripes of the wall paper, for example.

To a degree, this is a back-to-basics painting of the kind that this man of 50, already with a well-established clientele encumbered by fixed tastes, fixed expectations, now yearned to explore. And partially in defiance of those fixed tastes, those fixed expectations. Who is ever satisfied with the last great hit? Onward! He wanted to make his painting new, to remove its heaviness, its thickness of palette, to look back at what he might learn from the Impressionists, whom he had once rather despised. In fact, during these years he paid many visits to Renoir, now aging and ailing, looking carefully at what he was doing and had done, and probably thinking to himself: what was this light business all about? Is there something in this for me?

Having said that, this is by no means a self-conscious study of light effects with brushstrokes to match, but it is for all that a study in what the choice of a particular bright, even all-suffusing, light can do, how it can transfigure a scene that gives out on to the sea. Yes, the title seems to be at odds with the atmosphere of this room, which feels decidedly unwinterish.

It is surely too dancingly light, and too airily light-sipping, to be winterish. So Matisse has clearly decided to paint the scene in defiance of the season through which he is living or as a refreshing alternative to its slightly oppressive weight – just as he is also painting it, we cannot but feel, in partial defiance of those clients who will be looking out for physical evidence of the boredom of seamless continuity. He does it with a kind of bold insouciance, as if he can trust his own mastery of the loose effect, as if he knows that he does not need tonal thickness or any thickness of stroke. Let the light touch work its thin magic, as it clearly does.

About the artist: Henri Matisse (1869-1954)

The paintings of Henri Matisse seem to run counter to so much of what we are inclined to believe about the art of the 20th century. They show us that the idea of surface can be just as profound and enthralling as the idea of depth, that the art of the century itself was not entirely oppressed and defined by misery and angst, that there was space too for a kind of unrelieved joyousness, a celebration of the sheer, colourful wonder of the world.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments