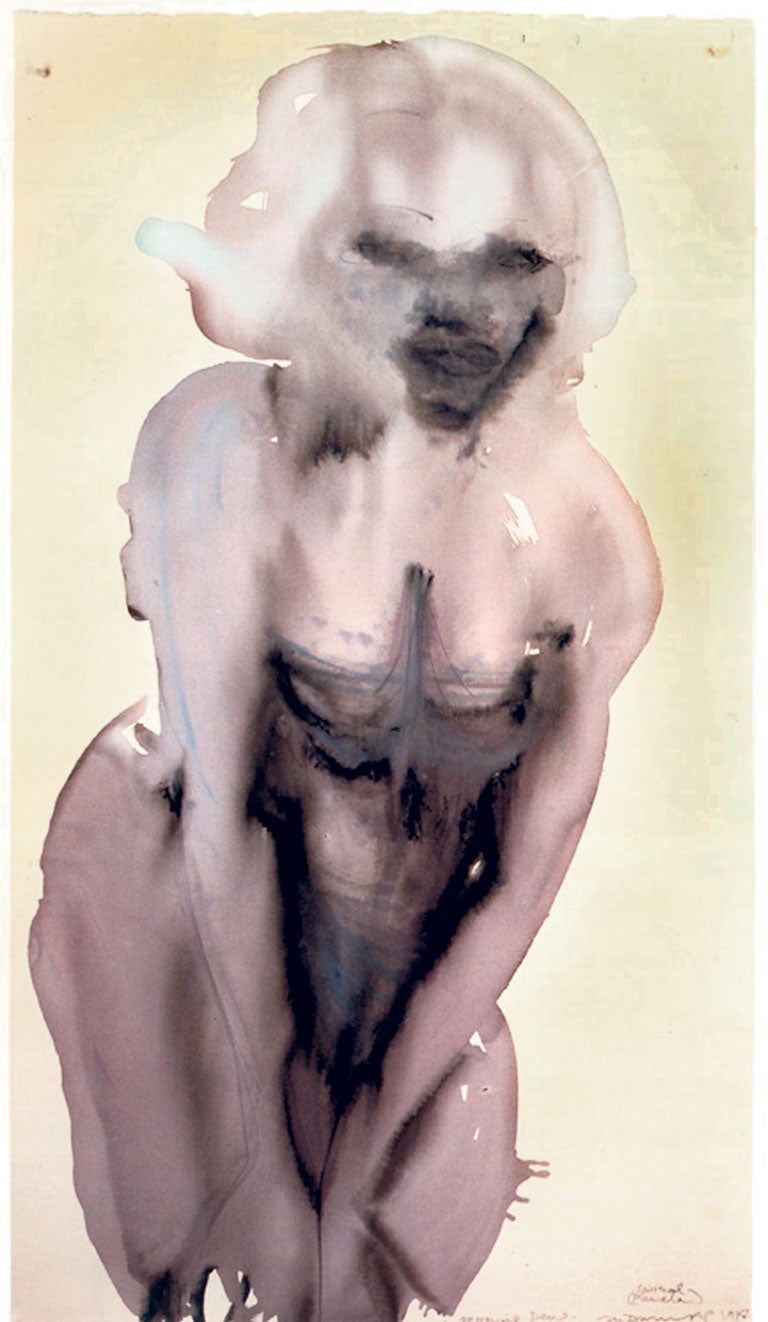

Great Works: Morning Dew 1997 (125cm x 70cm), Marlene Dumas

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Some of you may not be very familiar with the work of this South African artist, with a French name, who lives in Amsterdam. You may not even know that one of her paintings, when sold at auction in 2008, made her then the most costly living female painter in the world. We could speculate that the very fact that some of you may not know these things is yet another stark message about male domination of the art world. Discuss.

Marlene Dumas almost never paints a naked man. She has painted naked women over and over again, often unclothed, contorted and teasing. Her most effective medium is watercolour, and this painting is a mingling of ink wash, watercolour and metallic acrylic. Watercolour, still so often regarded as the insubstantial medium of Sunday painters (although Turner proved otherwise on a magisterial scale), has gained authority by her use of it in portraiture. Her paintings have a fluid, loose, ghostly quality about them, as if the portraits are of individuals who are both emerging into being and sliding back into a kind of formless nothingness. The body – her bodies often look quite helpless – craves substance, presence, but that is being, in part at least, denied. The colour, a kind of overall pinkish, purplish, washed-out bruising in this case, is used very sparingly where it is used at all. It tends to bleed in and out, to intensify momentarily, and then to fade back again. Sometimes it disappears altogether.

We see right through this woman. There is something both heartfelt, yearning, and strangely hard and pitiless about the work. It is stark and pin-upy brash, but it also seems to strive to move and engage the onlooker. She leans towards us, offering us that gross pout, her hair loosely tousled in a heaped up, blown-about Marilyn sort of a way. The painting looks both two- and three-dimensional, three-dimensional towards its centre, two-dimensional as you move towards its outer edges. In fact, at its outer edges it looks like the fleeting suggestion of a painting, a painting barely begun at all. Look at how she has painted that left leg (your right), for example – is that any more than a single, slightly splashy stroke? Its substance is fading away even as we look. In fact, her images often look like lingering after-images of which we simply cannot rid ourselves. Is it offering us a cheap thrill? Its subject matter often seems to suggest as much, but it is too lonely to be very titillating. Dumas once said that she regretted the fact that in her opinion – others may beg to differ – great paintings (unlike music, for example) does not make us cry, that they are too artful, too calculated, too quickly available to the eye all at once. There is no slow unveiling, as might happen in a work of music, for example. There is never the stunning impact, which might be the equivalent of the voice of Aretha Franklin.

Wrong. Surely. The very fragility of this blowzy woman stirs us.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Marlene Dumas, who was born in Cape Town in 1953, is a painter who works at the margins of respectability. In her charged and deeply troubling portraiture, she shows bodies unclothed, dead, in pain, and at many points in between. She raises troubling issues relating to gender, race and morality. Her paintings, often in watercolour, are intense psychological studies, not easily dissected, not easily interpreted. It is for this reason, that at a certain point in her career, she decided to call herself "Miss Interpreted".

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments