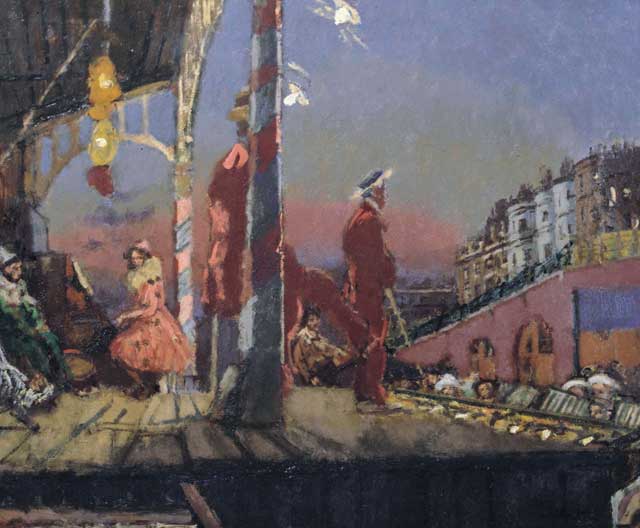

Great Works: Brighton Pierrots 1915 (64x76 cm), Walter Sickert

Tate Britain, London

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Many poets and many painters have found a fitting image of themselves in the cheerfully melancholy likeness of the clown, in the putting on and the taking off the mask of the self. Think of Picasso (who was forever painting Pierrots and Harlequins), Goya or, in our own day, Paul McCarthy. The poet Charles Baudelaire wrote of this very fact in a poeme en prose of 1861 called "Le Vieux Saltimbanque". In that shunned and decrepit creature, Baudelaire mused, "I could see an image of an old man of letters, a survivor of his generation, which he had delighted so brilliantly; akin to an old poet without friends, family, children, made wretched by misery and the ingratitude of the public." Those bitter words said much about the recent rejection of his great collection of poems, Les Fleurs du Mal.

Almost 60 years later, in the midst of war, Walter Sickert painted a troupe of pierrots, in Brighton. This was familiar country to Sickert. He too had spent some time treading the boards. In spite of its gay colours – although it is painted in oils, it looks as if it might have been drawn with the aid of an exuberant fistful of child's chalks – an air of dragging sadness hangs over this work, infecting it like a stain. The focus of our attention is a group of clownish entertainers, performing to a meagre audience. Their identity is known. They were called The Highwaymen, and they were managed by a local impresario called Jack Sheppard. The evening sky – the light is evidently falling – is painted in a delicious admixture of colours. Its pinky-orangey-yellowy-purply-reddish-blue reminds us of face make-up and stage lighting in its strange air of garish artifice, as much rouged-up flesh as a phenomenon of nature. There is almost nothing of war in this painting (which was made during the year of the Gallipoli Campaign) except that strangely ominous colouration of the sky – and the fact that so many of the deck chairs remain unfilled. That degree of understatement is more than enough. Sickert was much taken by places of popular entertainment. He painted circuses and music halls again and again in the course of his long career. Like some of his earliest heroes, Hogarth, Rowlandson and Cruickshank, he had a passion for low-life scenes. He found an earthy truth in them, which was not perhaps to be found in more refined cultural locations.

This is a painting which, from the point of the viewer, looks just a touch off-centre. It is as if we are not quite seeing it from the correct vantage point. As onlookers at the scene, we have found ourselves off to the side of the makeshift stage, in the position of the less fortunate spectators who have not paid quite enough to get the best of views. The fortunate ones are those whose faces we can see quite as well as – in fact, almost better than – the faces of some of the entertainers themselves. The best view of all is being enjoyed by the inhabitants of that handsome Regency terrace, which is set swankingly high to the right of the stage.

Some are dressed as Pierrots, others wear suits and straw boaters. The foremost entertainer, the one who is standing at the front of the stage, facing away from us, is wearing a straw boater, its brim singled out in a dazzling loop of white. He brandishes a drooped cane. There seems such lassitude in that droop. Although some vamping of the joanna is evidently going on, the pianist herself, who seems to be looking directly back at us, has an air of idling weariness about her. The entertainer at the front of the stage seems singled out in order to embody the mood of the painting, which is curiously flaccid and lifeless. He is utterly motionless and, being separated from most of the rest by the column of the makeshift proscenium arch, he looks oddly isolated too. Where has all the gaiety gone, all the rollicking interaction with this seaside audience? There are others disposed about the stage too, like so many lifeless props. Another, dressed identically to the man at the front, is partially obscured by that candy-striped column. His face is not visible at all. The best that we see of him is a kicking leg.

The entire scene possesses a kind of sketchy, makeshift fragility. The application of single, frisky dabs of colour gives it the appearance of a thing that has been composed of bits and pieces, precarious fragments of itself, and which may yet collapse back into those component parts. This helps to emphasise the fact that what is going on here is brilliantly, beguilingly, fleetingly ephemeral, the stuff of passing dreams. The painting feels a little too small for its own good. Generally speaking, scenes like this seem to demand the trumpeting and the posturing of size. Not so this one, which is shrunken into itself, almost self-reflective. In short, it seems to be showing us the end of something, a last, brave huzzah.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Walter Richard Sickert (1860-1942) was an important and influential painter for more than half a century who gave vigorous new life to the figurative tradition. His first master was Whistler, who taught him to follow his instincts and to paint his own image of the real. Much given to low-life scenes – one of his most celebrated and most controversial sequences of paintings took as its theme the Camden Town Murders – he also painted society portraits, cockney music halls, the brilliant artifice of Venice, the low-life of Dieppe and, anticipating Warhol and the 1960s, used newspaper images as source material. A man much given to histrionic gestures, he painted, drank and read hard.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments