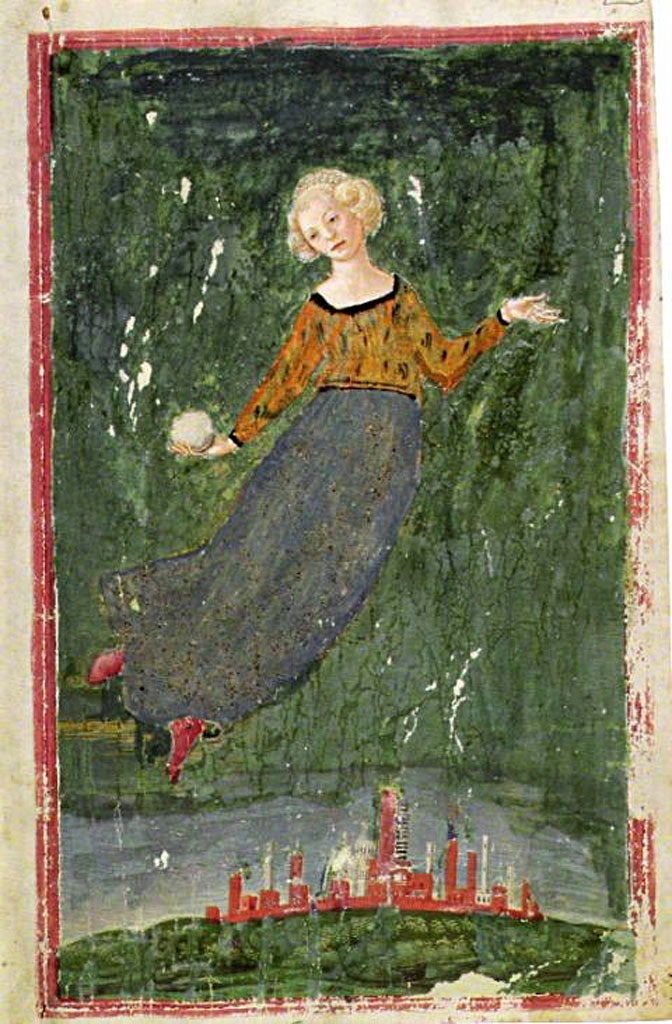

Great Works: Bianca Saracini suspended aloft above the City of Siena, 1472-74 (20.7cm x 13.8cm), By Francesco di Giorgio Martini

Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze

Your support helps us to tell the story

In my reporting on women's reproductive rights, I've witnessed the critical role that independent journalism plays in protecting freedoms and informing the public.

Your support allows us to keep these vital issues in the spotlight. Without your help, we wouldn't be able to fight for truth and justice.

Every contribution ensures that we can continue to report on the stories that impact lives

Kelly Rissman

US News Reporter

Sometimes a painting seems to glory in its imperfections, its evidence of weathering. To such an extent, in fact, that when, by contrast, we pay a visit to the Frick Collection in New York, for example, we find ourselves feeling suspicious of the degree of polish and perfection to be found in their Old Master paintings. This Holbein, that Bellini look almost newer than new...

Not so here. This painting is suffering from an almost tragic degree of neglect. The paint itself has worn away; the quality of such restoration as the painting has undergone is poor in the extreme – see where that raggedy line of green ends, just above the city's tallest tower. For all that – and perhaps, in part, because of it – it is still wonderful.

This noblewoman, suspended gracefully above the easily recognisable silhouette of Renaissance Siena, looming hugely and magnificently, skirt billowing over its finicky tininess, has a lovely sense of weightlessness about her. Her legs are drawn back, as if blown into that shape by currents of air. She seems to be carried back and away from us even as we stare at her. She is entirely at her ease here, we feel, as if in someone's comfortably dependable arms.

Her graceful feet, pointily shod in the red of the city itself, seem to be pushing her along. She seems more sacred than secular, virgin-like or angelic, and yet in spite of all that, she also looks entirely human. Almost nothing suggests that she is other than human – except, perhaps, for one tiny, miraculous-looking detail, the snowball she holds out, quite loosely, in her right hand, which is a glancing reference to a sacred painting by Sassetta called Madonna delle neve ("Virgin of the snows").

The painter, in the depiction of the face and the treatment of the hair, seems to have gone out of his way to make sure that she will be recognised for the great beauty that she undoubtedly was at the time that she was painted. There is a solemnity, a real gravity, about the expression on her face, which may represent the twin burdens of being a symbol of beauty and nobility. And yet the painting is also, simultaneously – and this is surely part of its enduring appeal – utterly light and fanciful at the same time, even a little Mary Poppins-ish, snatched, if you like, from the pages of a children's book.

Not a bad guess, you might say. This very small painting, housed in a library in Florence, is indeed the frontispiece to a book, a book of poetry. The painting does have qualities of naivety. Look at how those puffed-out trees are painted below the walls of the city, for example. Their representation is simplified in a child-like way. The book itself is a secular hymn of praise addressed to Bianca herself, who was a prized contemporary embodiment of Sienese beauty.

About the artist: Francesco di Giorgio Martini (1439-1501)

The extraordinarily industrious Francesco di Giorgio Martini, architect, painter, sculptor and engineer, was a man whose talents were much in demand in the second half of the Sienese Quatrocento. He decorated coffered ceilings, made secular and religious paintings for public and private patrons, and was also in charge of the city's water supply. At the end of his fourth decade he was wooed to Urbino, where he served as architect to a court that also had Piero della Francesca in its employ. His last decade saw a return to Siena, where he became engaged in works of military engineering.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments