Carpaccio, Vittore: The Apparition of the Ten Thousand Martyrs (c.1515)

The Independent's Great Art series

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference. Also in this article:

About the artist

Counting sheep, the proverbial technique for inducing sleep, isn't a form of arithmetic. As the imaginary ovines pass before the mind's eye, you're not keeping a tally. You're keeping up a steady and repetitive rhythm, fixed on this succession of identical units, coming at regular intervals, going on indefinitely. You're after a hypnotic monotony. A picture can have the same effect.

The Christian legend of the Ten Thousand Martyrs is a story with a number attached, but it's so large it just signifies as a great multitude. What can you do with Ten Thousand Martyrs? March them up to the top of the hill? Not far off, in fact. The Ten Thousand Martyrs were supposed to be an entire Roman legion who, during the reign of the Emperor Diocletian, had all converted to Christianity. Ordered to worship pagan gods, they refused - and were marched up to the top of Mount Ararat and crucified en masse.

Vittore Carpaccio painted an altarpiece image of this execution extravaganza. The Ten Thousand Martyrs of Mount Ararat is densely packed with naked, tortured figures. The scene piles up and stretches away into the distance. You almost believe that, if you tried, you'd be able to count 10,000 individual martyrs. But, as part of the same commission, Carpaccio painted another picture, of a more recent, more local incident.

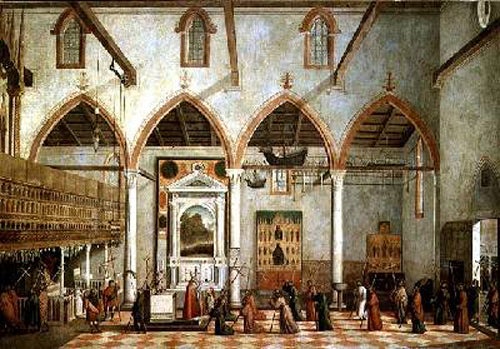

In 1511, Francesco Ottobon, a prior of the Venetian monastery of St Antonio di Castello, had a dream in which he saw himself at prayer in the monastery church. Suddenly, there was a great noise outside. The church doors opened. A multitude of men, carrying crosses, began to walk up the aisle in procession. At the main altar they knelt, and were blessed by a figure whom Ottobon identified as St Peter. They passed through, "two by two, resounding sweetly in hymns and songs". Otto-bon recognised the stream of pilgrims in his dream as the 10,000 martyrs of Mount Ararat. A few years later, Carpaccio pictured this dream in The Apparition of the Ten Thousand Martyrs.

Most of the scene is the church itself. It's a working church, filled with accumulated, untidy detail. You notice the images on the facing wall, traditional gold-framed icons and - above the side altar - a work of contemporary Venetian painting, an atmospheric landscape, school of Bellini. You notice the abundance of dangling ex-votos, thanksgiving offerings, effigies of bones and body-parts and model ships, signifying the donor's delivery from accident, disease or shipwreck. The wonder takes place in a realistic setting.

The space of the church is like a box. Its big, airy volume is symmetrically arranged, and viewed, from floor to rafters, in four-square perspective. It's set straight on to the picture's view, as if the picture's frame was the rim of this open box. It's like a high proscenium-arch stage, and it has two entrances, one on either side. Through this lucid space, across the bottom, threads the double file of robed walkers.

Carpaccio animates the procession, putting the advancing figures in a sequence of poses that break down their actions in a stage-by-stage way - gradually sinking to their knees as they approach the altar, rising again, passing either side of it, moving on. But these individual poses don't interrupt the flow of the line. Everything stresses its steady, continuous progress. The procession is straight, and runs exactly parallel to the picture, and the figures are spaced out at pretty regular intervals. This is a line that keeps coming, that goes on and on.

Unlike in his mass-crucifixion scene, Carpaccio doesn't try to persuade us that we have thousands of men crammed into our view. There are only about 25 figures crossing this stage - with a few more glimpsed through the open right-hand door way, part of the waiting queue in the ante-chapel. But it is enough. The picture suggests enormous multitudes by implication. We have a line of men crossing our field of view, but it's a line of which we can see neither the beginning nor the end. We see only the brief section of it that is now appearing between entrance and exit. What is offstage might be infinite. The queue could go on filing past for ever.

The dreamer himself is the little man in white, kneeling at the railing at the left of the painting. He turns round to catch, over his shoulder, the extraordinary sight. As sometimes happens, the dreamer himself figures in his own dream. But what makes the scene most dreamlike is the parade of pilgrim-martyrs. This continuous and potentially endless stream of individual figures passes through with a hypnotic, repetitive, sheep-counting effect. It creates a sense of transfixed, ongoing, timeless flow. Carpaccio's The Apparition of the Ten Thousand Martyrs is a trance-state image.

Vittore Carpaccio (1450-1525) is one of the great painters of the human scene. Of the same Venetian generation as Bellini and Giorgione, he was less concerned with visual atmospherics. In his scenes, every detail is clipped and clear. His dramas occur in single rooms, among fantasy architecture and realistic street views, in formal processions and killing fields. His greatest works remain in Venice: the St Ursula Cycle is in the Gallerie dell'Accademia, and the scenes from the Lives of St George and St Jerome are in the Scuola Dalmata di San Giorgio degli Schiavone.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments