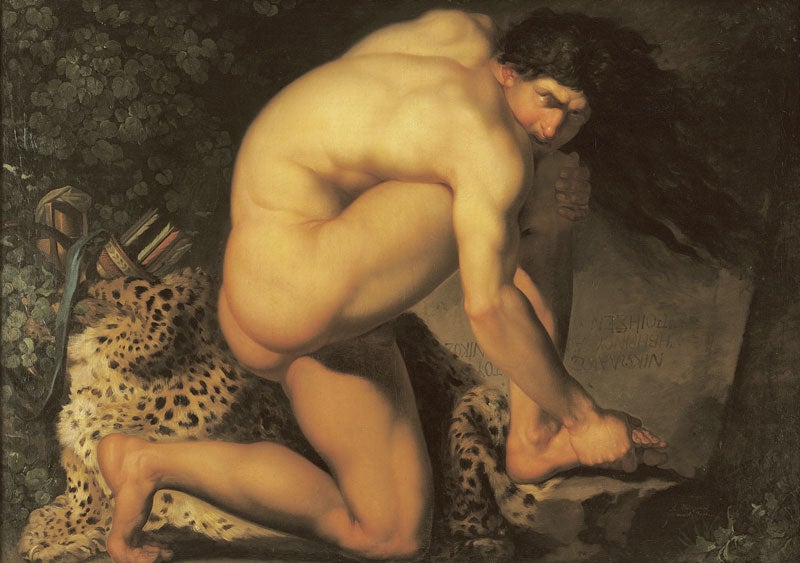

Abildgaard, Nicolai: The Wounded Philoctetes (1775)

The Independent's Great Art series

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Don't think that the old masters were always masters of subtlety. They could be as crude as we can. An affinity has often been noticed, for example, between the musclebound protagonists of Romantic painting and the superheroes of post-war comic strips.

Look at Spider-Man, the Incredible Hulk, the Mighty Thor, the Fantastic Four, the X-Men. Then look at the work of artists such as Henry Fuseli or William Blake. There's certainly a likeness: the bursting musculature, the bendy, stretchy anatomies, the power of zooming flight, the explosions of violence, the mythic milieu, the general cult of physical energy and clout.

You can believe that late- 18th-century art actually inspired late-20th-century cartoonists. The real explanation, though, may be broader. Both Romantic art and superhero cartoons drew, however remotely, on a common source: that great originator, whose influence gets everywhere, Michelangelo.

What links the Romantics to the comic strips is mainly the crudeness of their creations: Michelangelesque bodies that are super-malleable, super-inflated, and verging on the ridiculous.

Another of those hero-makers was Fuseli's friend, the Danish painter Nicolai Abildgaard. In his picture of the wounded Philoctetes, you see a body that looks back to the Sistine Chapel, and on to the Hulk. But if you don't know the story, it may be unclear what it's up to. This isn't a picture of physical power. It's a picture of physical pain, powerfully suffered.

Philoctetes, the great archer, on his way to the siege of Troy, was bitten on the foot by a snake. The incurable wound began to suppurate through its bandages with a revolting smell. His life became an endless round of shrieking agonies. His comrades abandoned him alone on an island, and sailed on.

The legend offers the painter the challenge of depicting pain, and little else. But it's a difficult pain to do stirringly, because it's so ignoble. It's located in an undignified part of the body. It's of a disgusting nature. It's not borne with fortitude. And it's clear that Abildgaard, though unafraid of melodrama, felt this was a problem. He doesn't stress the clutched hurting foot. He doesn't show a howling mouth. He leaves out the filthy bandages. He gives us physical pain as a general wracking torment, expressed through the convulsion of the entire body.

The hero is bent over on himself, chin to knee. The curve of his spine makes an almost perfect quarter or third of a circle. His abdomen is crooked like a joint. The whole unit of right thigh, buttock, torso, right shoulder and upper arm looks like a clenched fist from the side.

The figure is both contorted and distorted. The distance from right buttock to right knee is weirdly extended. The far side of the back rises like an appendage, a fin of muscle, tacked on to add extra struggle. The left leg seems to come from a larger man. This anatomy is a bit of Frankenstein collage, fused together and pulling apart. It all makes for strain.

On top of that, the artist applies pressure. There is nothing indirect about his means. If you want a flagrant example of how a picture's rectangle can be used for expressive effect, it's here. The clenched body is held clamped in a vice-like grip between the picture's top and bottom edges. Its toes and kneeling knee press hard against the frame.

There are more subliminal pressures, too. Diagonal forces descend on this figure from the upper left, to hold it down, so to speak, in its folded-over posture. One of these forces is the light, which, as it falls, casts two strong diagonal shadows across thigh and calf. There's also the wind, blowing the man's streaming mane of black hair in the same diagonal (like a scream, though its tangled length also indicates his long isolation in a wilderness). His right forearm, and the dark slanting ridge of the leopard skin between his legs, echo these driving diagonal forces.

It's a great show of pain, but more theatre than empathy. And Abildgaard can't resist another aspect of his nude. The hero bends over. Like last week's Great Work, Boucher's Mademoiselle O'Murphy, this is a buttocks-focused picture. The swelling shape of light that forms on the inside thigh nudges up between them. Not subtle, but a subtext of sorts.

The Artist

Nicolai Abildgaard (1743-1809) was one of the first Danish painters to make a European name. He has been called "the father of Danish art". In the 1770s, he went off to Rome, where he met Henry Fuseli, the highly original, self-taught Swiss-British artist, and they studied Michelangelo.

This is the period that produced his wildest pictures, above all, The Wounded Philoctetes. Later, back in Denmark, he adopted a calmer, more classical mode, but still pursued Romantic subject matter.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments