Can a stately home be where the art is? Yves Klein at Blenheim is the latest artist intervention in a grand residence

From Jeff Koons at Versailles to Damien Hirst at Houghton Hall, artists have muscled in on some seriously imposing architectural spaces. But how does the work fare?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A brief art lesson to begin with.

What exactly is the difference between an Installation and an Intervention? An Installation (I have capitalised the word in order to exaggerate its legitimacy) is the milder mannered – if not the softer spoken – of the two. I call it milder mannered, and perhaps less predatory, because it does not seek to spread its influence beyond the space in which it is staged.

Artists often do installations in groups of four, six or eight. They might colonise an entire room. An installation is likely to be mixed-media. Here is a fictitious example of the kind that you might have seen at the Centre Pompidou in Paris at any time over the last couple of decades:

Despair consists of various elements, all rather loosely conjoined: a nervily shot film of an underground passageway in almost complete darkness; a goodly length of fiercely knotted rubber tubing; a wall of barbed wire, lolling, if not stirring, in a mild breeze activated by a semi-hidden machine; and, on a temporary wall, a barely readable drawing of a human face, perhaps partially erased in anger or despair.

You walk in. You experience all that there is to be seen and felt, much or little as the case may be. And then you walk out again and continue with your life along the Rive Droite, very pleasant too. An installation is that self-contained. You carry it away with you. And then you drop it – if it thoroughly deserves to be dropped.

And what of an Intervention? The much more robust and swaggery of the two and, for a change, I shall cite a few examples which actually happened – and one which opens this week at Blenheim Palace. An intervention is the muscling into an architectural space (which has been in existence for perhaps decades or even hundreds of years) by a single artist or several.

Our four examples carry us across the waters to the Palace of Versailles (the dotty, grand baroque extravagance of a French king, all vain self-mirroring), back across to a trio of modest cottages called Kettle’s Yard, on the edge of a small and self-important market town in England called Cambridge, up to Houghton Hall in Norfolk, Cholmondeley’s residence, where various works by Damien Hirst currently sit pretty amidst the ancestral blah-blah, and then to Blenheim Palace, whose reputation was so recently stained by the vulgar presence of Donald Trump.

Jeff Koons, that cheery, near manically self-applauding showman son of a furniture dealer from Pennsylvania, whose works are fabricated (to his very exacting specifications) by teams of eager, well-rewarded apprentices at his studio in Chelsea, New York, showed himself off in all his brash and tawdry ingloriousness at the Palace of Versailles in 2008.

How did his giant balloon dog and his suspended lobster fare beside the Sun King’s act of megalomaniacal architectural extravagance? Did they look out of place? Not at all.

Koons’s presence there brought home to us to what extent the palace itself seems quite at one with, all this kitschy, over-the-top, hysterical brashness. Are not Louis XIV and Koons kindred spirits at heart, in so far as they both want to make the grandest gesture of which they are capable? That is how Koons described his own aspirations to his breathless admirer Norman Rosenthal in a book-length interview published in 2014.

By comparison with Koons, Damien Hirst, currently showing off his Colour Space paintings at Houghton Hall, a Palladian mansion in Norfolk, feels a little underwhelming above the chimney breast and the ancient four-poster, as if he has not quite risen to the architectural occasion. It is so difficult cutting a creditable dash in someone else’s state rooms; these were created in the 18th century for our first prime minister, Sir Robert Walpole.

Is it perhaps a little easier in a group of small cottages, three knocked into one, such as Kettle’s Yard? There have been several interventions there, by Cornelia Parker and others, but not a single one of them has been particularly memorable. The space is too small, too intimate and its delicately posed collections of objects in that domestic interior too much the product of careful hand-crafting by its marvellous creator, Jim Ede. It feels almost impossible to break in.

And who would want that to happen anyway? The place resists improvement. It is already perfect. It seems to say, in its own quiet way: stay away please.

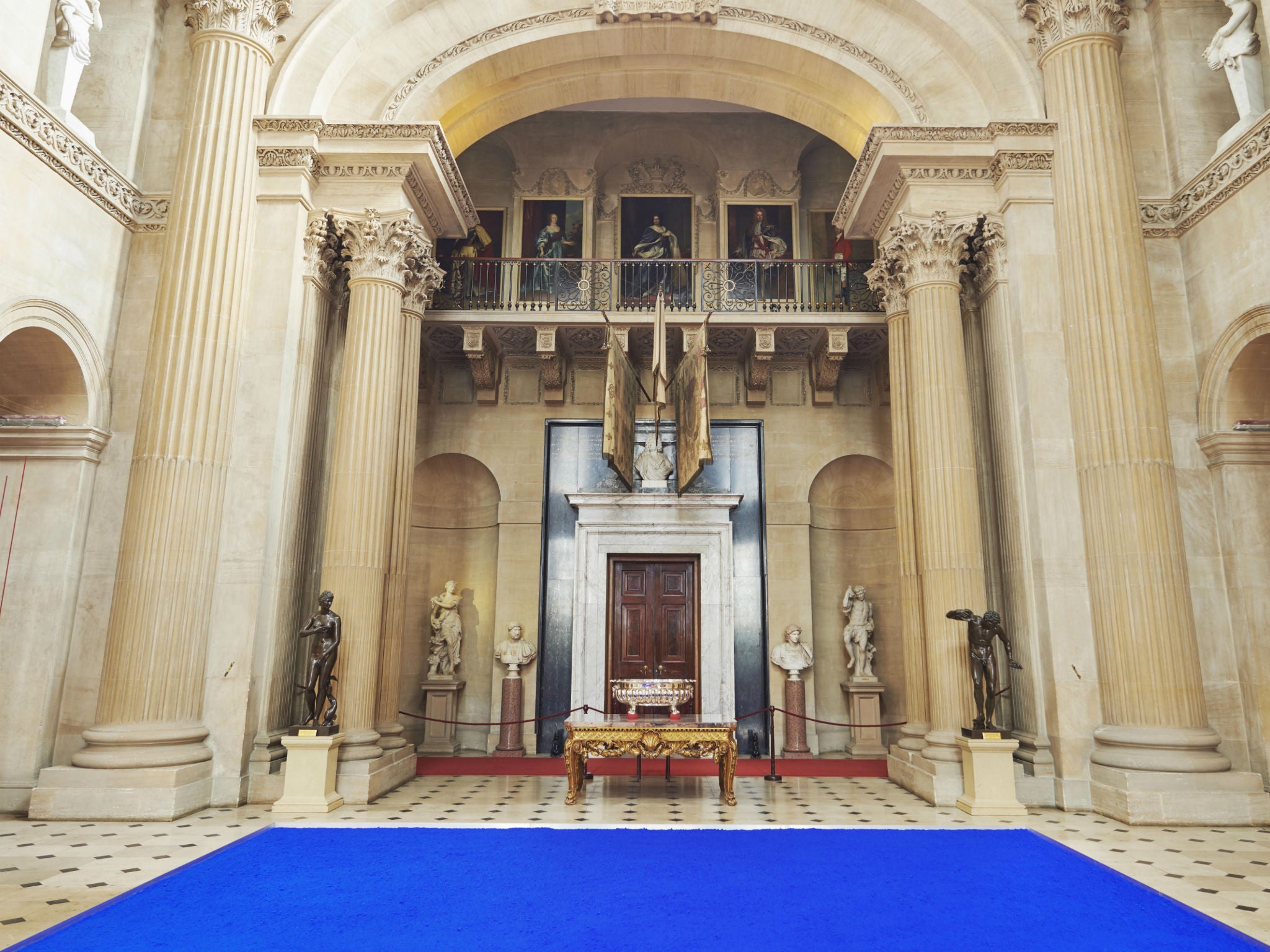

This week Blenheim Palace says hello to an intervention of more than fifty works by a remarkable, post-war French artist called Yves Klein who is best known for the strangely otherworldly quality of his intense, saturated blues.

It’s the fifth anniversary of the Blenheim Art Foundation (yes, they do these things annually) and it’s staged in collaboration with the Yves Klein Estate to coincide with the artist’s ‘90th birthday’ (he died in 1962, at the age of 34, perhaps poisoned by his own fixatives).

This is a much more professional job than we are accustomed to, genuinely searching in this most surprising of environments – Hirst looked ridiculously amateurish by comparison.

Blenheim itself is an act of praise, a gift from a grateful sovereign (Queen Anne) to the first Duke of Marlborough, who was the victor in the War of Spanish Succession which raged on through the first decade of the 18th century. His triumphs in battle defines its state rooms, from tapestries of mounted soldiery on their wheeling horses, to battle pennants commemorating great victories at Malplaquet and Ramillies.

How does Klein fare amongst all this martial triumphalism? Surprisingly well. In each room that his works appear, small or large, on plinths, in cabinets amongst the ancestral china, or on the walls, he seems to possess an air of cool self-sufficiency, a delightful, immaterial strangeness which never seems to be in conflict with its context.

There is give and take. There is no brashness, and no rude, crude elbowing aside.

This is intervention by tact and stealth, and if you choose to pay the stiff cost of entry to the palace – £27.50 – you can enjoy it at your leisure.

‘Yves Klein’ is at Blenheim Palace until 7 October

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments