Witches: A history of misogyny

The sexist abuse that haunts modern life is nothing new: women have been 'trolled' in art for 500 years. Deanna Petherbridge, co-curator of the first major exhibition on the subject, delves into a ghastly history

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.We live in a world where demonising dames is a co-ordinated sport of words and images. One instance that gripped me was a rally in 2011 when Australia's first female prime minister, Julia Gillard, was placarded as a witch and a bitch. The picture that sped around the world showed the opposition leader, Tony Abbott, haranguing carbon-tax protesters in front of a poster proclaiming "Ditch the Witch", with a silhouette of a hag with a pointed hat and huge nose on a broomstick.

That neat portmanteau image of sexist and ageist abuse is so commonplace that it could be defended as an "Aussie" joke, a bit of punning fun. But the symbol of the broomstick hag was not enough to encapsulate all aspects of Gillard's offending gender, so for good measure there were also posters with the term "bitch" surrounded by flames, to remind us she was a sexually active and dangerous woman. Gillard responded in a famous speech in the Australian parliament about Abbott's misogyny.

While this gruesome drama played out on our screens, I was preparing the exhibition Witches and Wicked Bodies for the National Galleries, Scotland, which ran last year. This was the first major exhibition on the subject to be held in Britain, and there haven't been too many elsewhere. I was gob-smacked that the visual stereotypes of misogyny that I was looking at in 16th- to 18th-century prints, drawings and paintings were still so potent, however simplistic.

The dangerous bitch and the hideous old witch are complementary representations, intended to show up women's iniquities and punish them, but also to warn and frighten men.

The monstrous old hag who is in contact with evil forces (such as the biblical witch of Endor) and the beautiful enchantress who turns men into beasts (such as the classical Circe) have been reinvented in many guises through the centuries in European art, literature, theatre and music.

The ancient crone – depicted semi-naked in early prints, so that viewers are repelled by her shrunken body and hanging, distended breasts – is riven with envy of youth, beauty, fertility and prosperity. In league with the Devil, she castrates and destroys by her ugliness, just as the beautiful young witch emasculates and corrupts by her beauty. The noisy old witch, like the screech-owl after which she was named in Latin, Strix, shrieks imprecations from her gaping maw, while beautiful Sirens open their mouths in honeyed songs to lure men to their destruction.

Goya would return to such powerful images at the end of the enlightened 18th century for political ends in his print series, often depicting the corruption of younger women by older procuresses or witches, brujas. So did Symbolist artists in the 19th century, identifying old hags and young women alike as the corrupters of masculine health, sanity and good order, carrying disease in their hideous or desirable bodies.

Contemporary female artists have also addressed the double stereotype. Paula Rego, a purveyor of deeply uneasy fantasy, has drawn images of old bawds sewing up girls for sale, and has dealt with the issue of female genital mutilation. The photographer Cindy Sherman has assumed huge prosthetic breasts and an open vagina together with an old hag's mask in a shocking composite image. At other times, she wears a false warty nose or is rooted as a witch in beds of slime and vomit.

Like theatrical representations, images of witches are not tied to the brutal facts of history. They persist because their fearful and repulsive aspects are laced with sexual titillation.

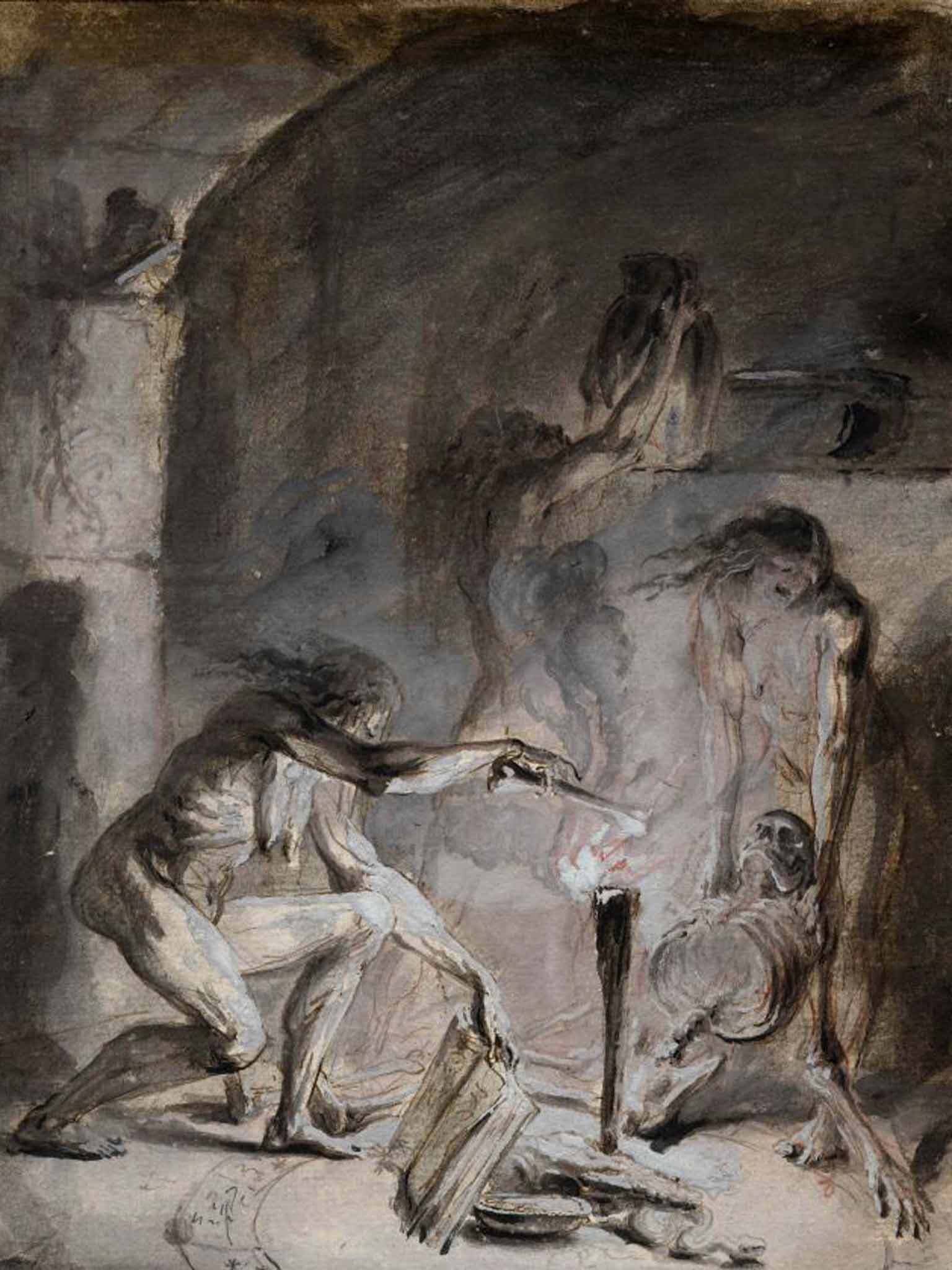

In the version of Witches and Wicked Bodies now at the British Museum, illustrations of supposedly learned demonological texts employ the same imagery as popular 17th-century broadsides. Young and old witches line up to kiss Satan's backside, or dance in the nude with demons at Witches' Sabbaths. They cook up foul messes of body parts in cauldrons, ride bare-bottomed on demons, or disappear naked up chimneys on broomsticks. Supposedly based on testimony recorded by jurists from confessions extracted under torture (testimony that was remarkably similar all over Europe), these prints serve to appal and excite, with just enough macabre excess to render the subjects ridiculous and deflect viewers from the real gravity of what is happening.

Men and children were accused of witchcraft alongside women during the centuries of the witch hunts in Europe, and punished horribly in great numbers – but the majority of those accused of the crime and heresy of witchcraft were women. Men are pictured as necromancers or alchemists, serious seekers after the truth; they age with dignity and grow beards. Old crones sometimes have beards, too, but grow snakes instead of hair on their heads, wreaking destruction on kings and commoners alike.

In the 19th century, they lost their teeth, so to speak – if not their noses – when the image of the pointy-hat-and-broomstick witch was sanitised for children's consumption. This left femmes fatale such as Lilith or Medea, so beloved of the Pre-Raphaelites, with nothing much to do except look sexily languid.

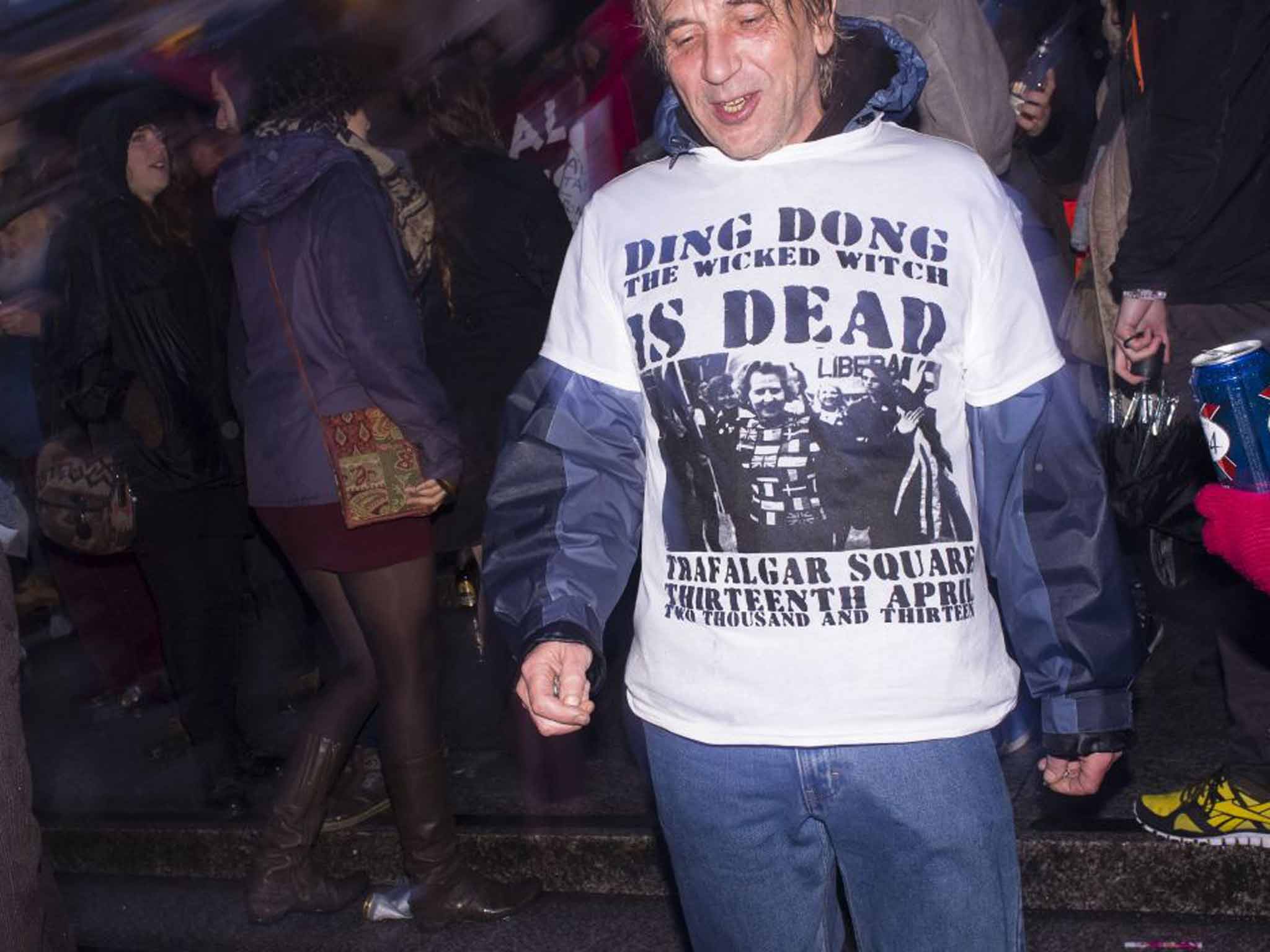

Satire is the leaven that keeps pictorial misogyny alive and fresh (as fresh, that is, as a dried dog turd that comes up nice and slippery in the rain). In satirical mode, then, let's assume we can connect a history of misogynistic visual representation with current manifestations of gender and age discrimination. Then it could be proposed that it is contemporary women's lack of humour that prevents them from identifying a hasty fondle by a parliamentarian as an innocent bit of fun, or "Ditch the Witch" as just a pun. We might suggest that it is their dearth of irony that prevents lower-paid women from understanding that the joke is on them in the unequal opportunities game. What about those reactionaries who objected to the popular obituary "Ding dong, the witch is dead" that greeted the death of Margaret Thatcher? We could suggest that broadcasters establish a parity of jokey jingles for future deaths across all political parties.

For those cheerless women campaigners and celebrities unable to laugh at the rape jokes or pictures of genitalia aimed at them online, we could explain how hilariously empowering these missives are for disempowered internet trolls.

Finally, we could remind the classicist Mary Beard (who probably suspects it anyway) that her legions of anonymous vilifiers hiding in black holes in cyberspace are bald blokes or alopecia sufferers who can't forgive her lively head of hair. They're as terrified of her compassion for their plight as they are rended speechless by her luminous intelligence.

Let's save the world with a little masculine humour and horror. Fee fo fum, by the pricking of my thumb…

'Witches and Wicked Bodies' is at the British Museum, London WC1 (britishmuseum.org), until 11 January

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments