Late flowering or failing: Did work by artists like De Kooning, Renoir, Matisse and Monet decline in old age?

As a new London show opens of late works by Willem de Kooning, who suffered from dementia, we look at other artists in old age and how their physical disabilities and cognitive decline impacted on their work

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Many great artists have wrestled with end-of-life impediments, from physical disabilities to cognitive decline. Let’s name some of them: Monet, Renoir, Matisse, Willem de Kooning. Could we also include Picasso and Titian? Perhaps.

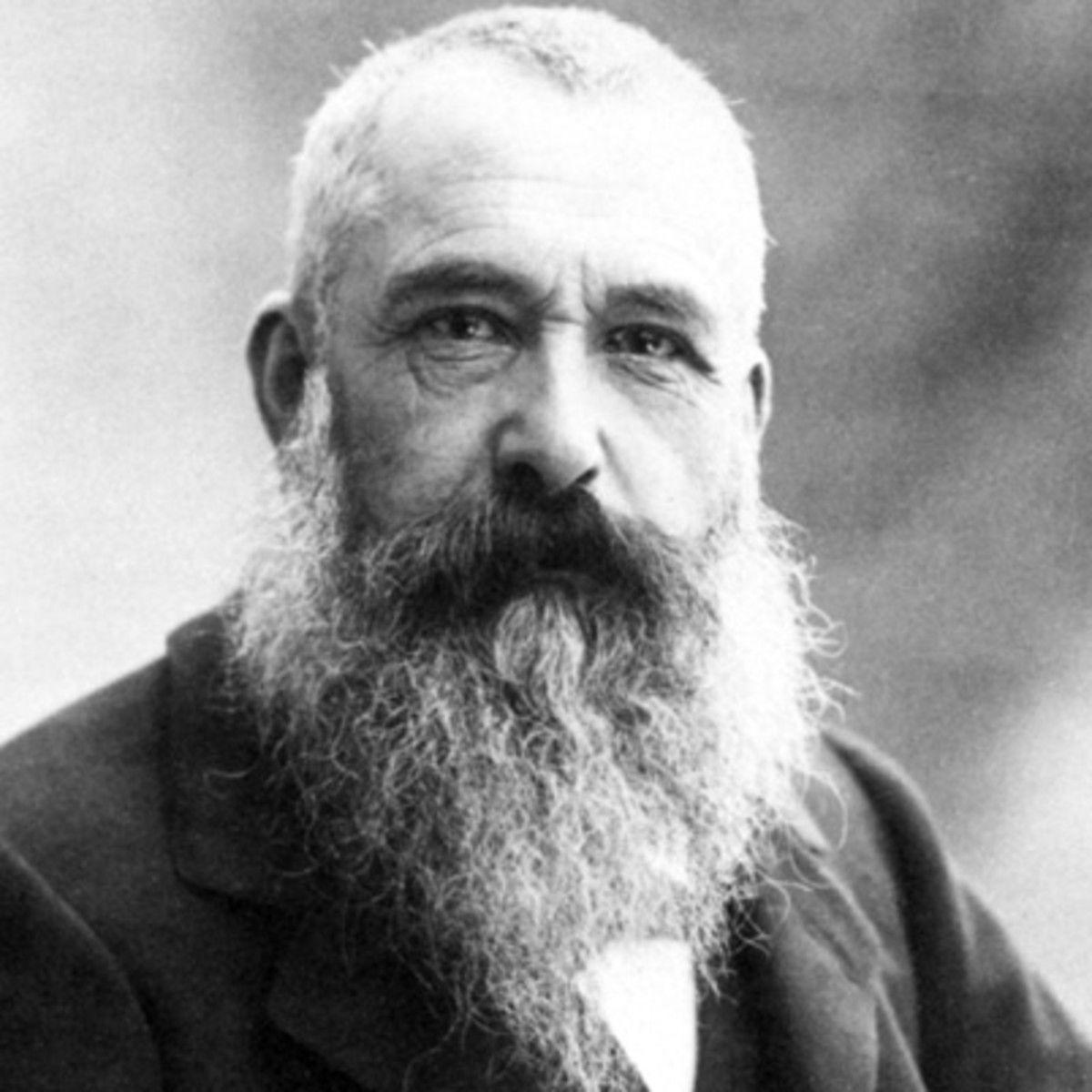

Some, like Renoir or Matisse, had fought back, dramatically. Matisse created his great cut-outs when, nearing life’s end, he was severely limited physically. A narrowing brought about a great outpouring and a great reinventing, you could say. Monet, too, found himself able to harness his advancing decrepitude, and even to break through to a slightly different way of making.

Monet’s cataracts were a plague and a misery to him in old age – but also perhaps an enabler. The great, late mural of water lilies that hangs in the Orangerie in Paris seems painted through not only a blur of seeing, but also through a haze of memory and yearning, in which each water lily comes to represent every water lily that he has ever painted in the past. The whole resembles a great, dreamy palimpsest. As his ability to see gradually declined, a fuzziness of seeing seemed to empower his craving to realise an image of the memory of the idea of the thing, so that what we see in front of our eyes both feels and looks like an emotional distillation of the essence of the water lily in all its fragile and evanescent floatingness.

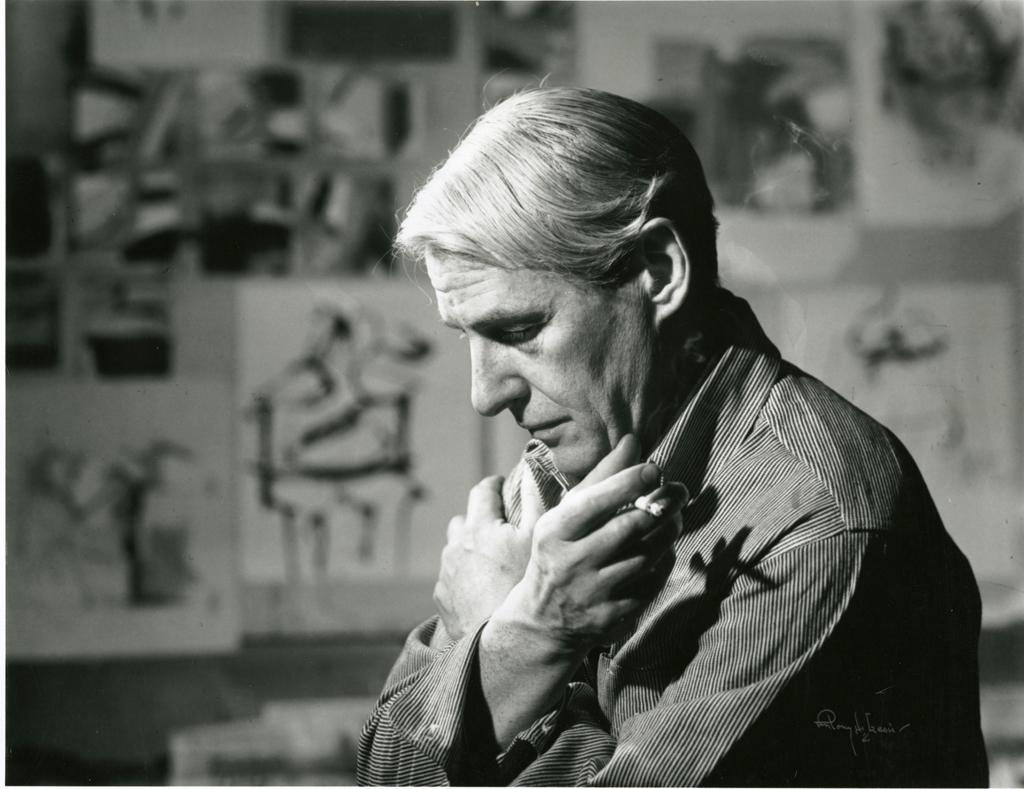

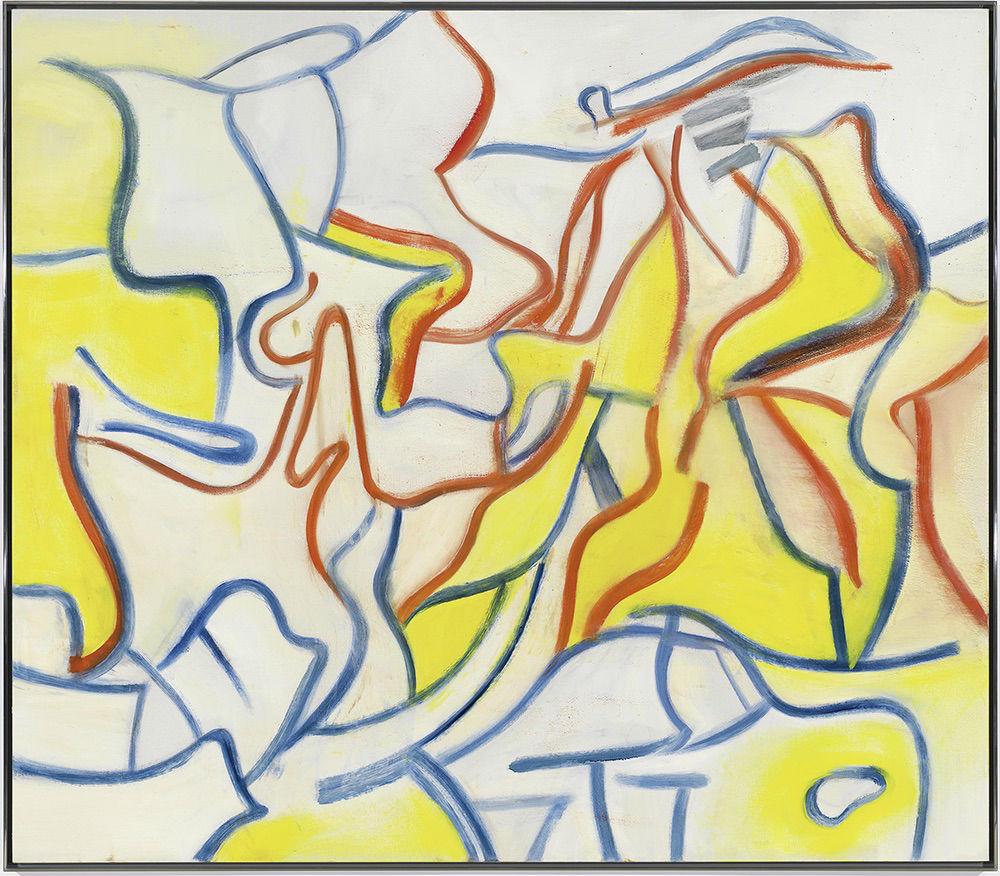

A new show of nine late works by Willem de Kooning has opened in London, in a gallery behind the Ritz. It is more than 20 years since a body of late works by De Kooning was shown in London – the Tate mounted a retrospective in 1995. In old age, De Kooning suffered from dementia, severe cognitive decline – he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in 1987, 10 years before his death – but he did not stop painting until 1991. In fact, his productivity sped up.

As with Renoir, to stop painting might be construed as something akin to giving up on life altogether. These late works can be read in two quite different ways – as can many disputed late paintings. They show evidence of a simplicity, of a paring back to essentials. The shapes that De Kooning made in some of them, the delicate overlapping of curved lines, is so far from the kind of dense, colourful frenzy of his earlier mature work. Does this mean that he could do nothing more than this by this late stage in his life, that his skills were limited to something quite this simple? Not at all, various critics have argued. This evidence of a new simplicity, this cleanness of line, should be regarded simply as a refreshing complement to everything that had come before, a conscious wish to simplify and pare back to essentials, and not some kind of evidence of mental or physical deterioration. The issue is a tricky one, of course. How we perceive the work may, for example, have an impact upon its perceived value at the auction house.

The director of Skarstedt Gallery in Mayfair, Bona Montagu, is in no doubt whatsoever that these nine late paintings dating from 1982 to 1987 by De Kooning that the gallery is showing are indisputable evidence of a late flowering. Look how influential these works have been upon such younger artists as Rebecca Warren and Albert Oehlen, she says. She bats away any argument that there is evidence of a decline. She rejects the idea of short-term memory loss.

Is that all Alzheimer’s amounts to, short-term memory loss? I think to myself. The whole subject is an irrelevance to someone like De Kooning, she continues, a great painter with six decades of work behind him. Instead, she describes a new confidence, an opening-out into new possibilities. “He blows everything open,” she says. “A new lightness is coming in.” Is it? Is it really? I mention the diagnosis with Alzheimer’s in 1987. She thinks I may be wrong about that. She recalls a date of 1989 – and says he stopped painting altogether in October 1990. I ask her whether the paintings are actually for sale, and for how much. Two of them, she tells me, and perhaps another if the possibility arises. And the price? Between $8m (£6m) and $10m (£7.5m) apiece. We are on less comfortable ground here, I sense.

I ask her if she knows how many of these so called late paintings exist. As there is no catalogue raisonné, she is unable to confirm the exact number of paintings by De Kooning in the 1980s, although she mentions that Robert Storr does refer to a number in his San Francisco Museum of Modern Art catalogue, based on his own research. My understanding, I tell her, is that he painted faster and faster as he entered his final phase, even one a week. Once upon a time it might have taken him 18 months to make a painting, I mention. Once again, she uses that fact – if it is indeed true – as a reason to praise him. This is surely evidence of a marvellous late facility, she replies.

As she does so, I think about stories I have read about less pleasant goings-on at the studio: that assistants would take a canvas away when they deemed it finished, and then present him with the next one in order to encourage the emergence of yet another signed late De Kooning. Is that gossip nonsense or not? Above all, she wants to talk about his renewal, his greatness. She refers to the profound influence of Arshile Gorky on his work. The dilemma for her, of course, is that she is both an apologist for his reputation and a dealer. Difficult. Very difficult. I look at the works, and look again. I remain wholly unconvinced that they represent a great, late flowering.

Is it really possible to establish the truth of cognitive decline in an artist long dead without exhuming the body? Some of our thinking may have to remain entirely speculative, based on evidence to be found in the late works themselves. A characteristic manner of painting may change over the years. Could that be a clue? Did Titian paint much more loosely in old age because his eyesight was failing and his motor skills were declining? Were Picasso’s late works child-like in their rough exuberance because his ability to control a brush was diminishing and his artistic vision more infantile?

Picasso’s late works were once vilified for their crudeness, and widely regarded as evidence of his failing powers. Now the judgement upon these works is much less harsh, much more nuanced altogether. Every artist (and Picasso perhaps more than most), the more recent argument runs, paints, fundamentally, out of the instincts of a child. He may also have painted like a child in extreme old age. And anyway, is it not also the case that he painted like a child from time to time at all points in his long years of making? Was he not, surely, a perpetual shape-shifter, forever reinventing himself, highly sophisticated one minute, crude the next? What is more, what some may count as evidence of decline, others may construe as merely a different vision of the world, perhaps a more untutored or infantile one, something more akin to Dubuffet and Art Brut.

A new biography of Renoir by Barbara Ehrlich, published this month, painstakingly charts the artist’s long, painful, 40-year decline into an arthritis so acute that by the end of his life his hands were like claws, and he was scarcely able to hold a brush. And yet he continued to paint. Painting was a source of supreme joy to him, and his paintings, from first to last, bristle with optimism. His vision changed too. Renoir, from first to last, idealised the female form. And as he declined into bodily impotence, that idealisation became even more exaggerated. In fact, we could easily substitute the word fantasy for idealism. Were not these great, curvaceous, eroticised, pneumatic forms, in part at least, the fantasies of a man whose painterly dreams were a primary source of emotional sustenance, a reason to continue to live?

And then there is the interesting case of JMW Turner. In the last years of his life, he painted works – scenes of Venice, for example – that came to be embraced by modernity because of their improvisatory nature. They were seized on as evidence that Turner was in advance of his times, perhaps even a precursor of Impressionism. And yet the answer may have been that his powers – and his eyesight – were failing, that he was incapable of doing otherwise. Or the works – and there were many left in the studio at his death – may simply have been unfinished or abandoned.

‘De Kooning: Late Paintings’ is at Skarstedt Gallery, 8 Bennet Street, London SW1A 1RP until 25 November

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments