When Little England climbed the stairway to Modernist heaven

In 1934 Ben Nicholson visited the Paris studio of Piet Mondrian. According to Charles Darwent, author of a new book, it was a moment that electrified – and divided – parochial British art

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.One afternoon in April 1934, Ben Nicholson climbed the stairs of an apartment building in a drab Paris street called the rue du Départ. A few hours later, he came down again with the air of one who had seen the light.

In 1944, he recalled the moment for the historian, John Summerson: "I remember after that first visit sitting at a café table on the edge of a pavement almost touching all the traffic going into and out of the Gare Montparnasse, & sitting there for a very long time with an astonishing feeling of quiet and repose (!)". The exclamation mark is telling. From the distance of a decade, Nicholson was embarrassed at his own enthusiasm, his un-English fervour in a French street. What he had seen at the top of the stairs had been in the order of a vision. Now the cause of his epiphany was dead, and Nicholson's wonder with him.

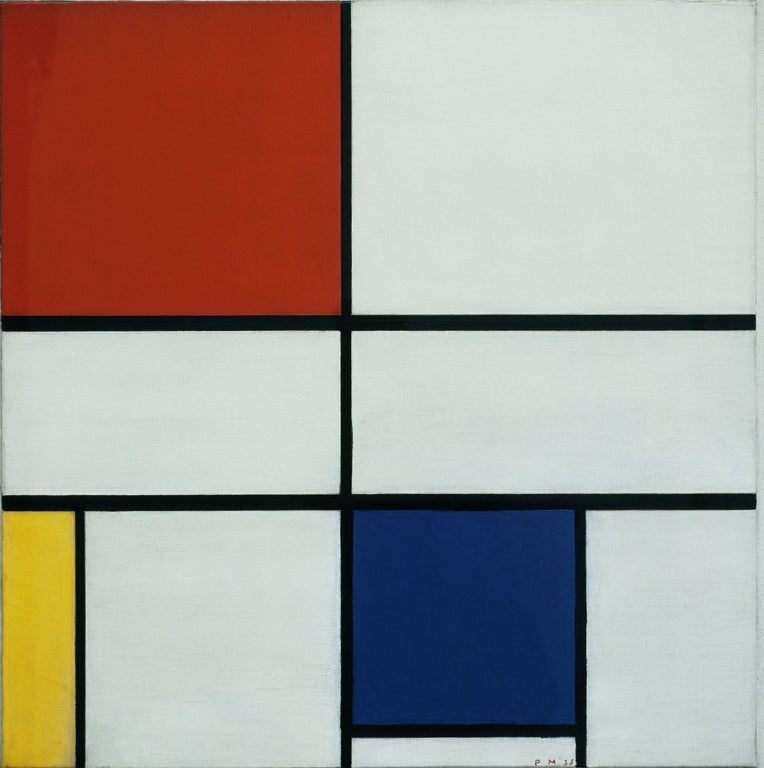

Piet Mondrian had moved into the rue du Départ in 1911; bar the years of the Great War, trapped in his native Holland, he had been there ever since. Already 40 by the time he arrived in Paris, the Dutchman had been a traditional painter of landscapes and trees. Picasso put paid to that. By 1917, Mondrian was working on his so-called plus-and-minus pictures, works that took the rationalising tendencies of Cubism to their logical extreme by doing away with representation altogether. In 1919, he had invented his own -ism: Neo-Plasticism, which blurred the distinction between art and design. By 1934, the studio at the rue du Départ was a vast, three-dimensional Mondrian in red, blue and yellow.

This was what Nicholson had found at the top of the stairs in Montparnasse. It is difficult, in these blasé days, to imagine the impact of Mondrian's studio on an English painter of the early 1930s. Herbert Read wasn't far off the mark when he wrote of a "slumbering provincialism that had characterised British art for nearly a century". The hippest art group in London in 1934 was the Seven & Five Society, and that was not very hip: the catalogue to the group's first show harrumphed that "there has of late been too much pioneering along too many lines in altogether too much of a hurry". Nicholson was seen as dangerously modern, and he, before his visit to Paris, was struggling to paint the kind of pictures Picasso had given up painting in 1908.

Nothing could have prepared him for the studio at the rue du Départ, with its all-white walls and movable rectangles of primary colours, still less for the seditious beliefs of the man who lived there. The result of their meeting is the subject of a show at the Courtauld Gallery called Mondrian-Nicholson: In Parallel; also, more broadly, of my book, Mondrian in London. The subtitle of this – How British Art Nearly Went Modern – tells the story of one of the strangest (and saddest) moments in English art history.

Within days of his visit to the rue du Départ, Nicholson was writing excitedly to the curator and collector, Jim Ede: "Here is how Mondrian puts it: – 'The study of the culture of art gives us the certainty that we are approaching a life which is no longer dominated by particular forms, and by unballanced [sic] "rapports" (oppositions): a life of pure relations, a human life'." Three months later, he warmed to his theme: "D. Jim, I think we are all on such a higher plane of understanding now. I would like to put all the misunderstandings of the past into the wastepaper basket."

Nicholson, at 40, hadn't simply found a new art. In Neo-Plasticism and Mondrian, he had found a new religion. Like any good convert, he set about spreading the word. Back in London, he dispatched other would-be apostles to the Neo-Plastic holy of holies. Over the months that followed, anyone who was anyone in the London avant garde toiled their way up the stairs of 26 rue du Départ.

First was John Piper, then a painter of naive, Nicholson-ish landscapes. Myfanwy Evans, soon to be Piper's second wife and the editor of Axis – the nearest England ever got to a Modernist art magazine in the years before the Second World War – followed a few weeks later. Mondrian, a jazz fan, asked her to jitterbug with him: Evans, finding him "pale, thin, shabby and conventionally dressed", swallowed hard and danced. Her lack of enthusiasm must have shown. When Henry Moore visited the studio the next day, he asked whether Mondrian would mind if he took Evans out. "Do," came the stony reply. "She's too representational for me."

Back in London and living with Barbara Hepworth, Ben Nicholson was doing his best to foment Neo-Plastic revolution. In November 1935, he, Hepworth and Piper staged a palace coup, re-naming the Seven & Five Society the Seven & Five Abstract Group. Members who refused to toe the abstractionist line were sacked. The following year, work began on Circle: International Survey of Constructive Art – a manifesto which Nicholson would edit with Leslie Martin, future architect of the Festival Hall. On the Continent, abstract art was withering under the onslaught of Hitler and Entartete Kunst ("degenerate art"). For a moment, it looked as if London would be the only place where Mondrian's brand of pure abstraction would survive. Alfred Barr, founder of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, said so in his epoch-making book, Cubism and Abstract Art: on 21 September 1938, Mondrian boarded a ferry to Dover with Ben's estranged wife, Winifred Nicholson, spurred partly by fear of the coming war but principally by a belief that the British were lovers of abstraction. A day later, he was living in London.

The story of the two years he spent at 60 Parkhill Road NW3 is both charming and, in an English sense, depressingly predictable. No sooner had Mondrian arrived in London than the art world turned on Nicholson and his revolutionary ideas. John Piper, resentful of his old master's power, declared abstraction "a luxury"; Axis, edited by his new wife, attacked it in tones that echoed Hitler's. These squibs might not have mattered had not Sir Kenneth Clark – he, later, of Civilisation – used his power as director of the National Gallery and Surveyor of the King's Pictures to kill the fledgling British abstraction as it was born. Writing in The Listener, then a hugely influential cultural mouthpiece, Clark voiced the view that abstract art "was essentially German". He might as well have put a gun to Nicholson's head.

What would have happened if Clark had been more scrupulous? On 21 September 1940, two years to the day from his arrival, Mondrian boarded the White Star liner Samaria for New York; he died there three years later. We think of his final flowering as an American period, of Broadway Boogie Woogie, his last, great canvas, as an American painting. Abstraction became a US possession, in the way that Impressionism had been French. It might so easily all have been English. Mondrian regretted having to leave England – he wrote to Winifred Nicholson from New York: "In those two years, I learned to love London very much." Among the things he admired about us were our gas fires, escalators and, implausibly, our cuisine; also garden gnomes, which he may have mistaken for dwarfs from his favourite film, Snow White. Mondrian felt that London changed his art, as letters to his brother, Carel, show. Without the time in Belsize Park, there might have been no Broadway Boogie Woogie. As it was, abstraction in Britain was dead in the water. It would be 20 years before it recovered, and by then its ownership had gone elsewhere.

'Mondrian in London: How British Art Nearly Went Modern' is published later this month (Double-Barrelled Books, £16.99). 'Mondrian-Nicholson: In Parallel', Courtauld Gallery, London, from Thursday to 20 May

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments