Truman Capote gave David Attie his big break - so why did the photographer never speak of their relationship?

Decades after his father's death, Eli Attie finally dug through his father's archive to search for the truth

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Truman Capote effectively launched my father's career. Which is something I learnt 18 months ago, decades after my father's death.

If that seems odd to you, well, it's odd to me, too. The road to publishing Brooklyn: A Personal Memoir by Truman Capote with the Lost Photographs of David Attie has been filled with strange accidents, surprising discoveries, and incredible good fortune. And, oh yeah, the brilliant work of David Attie.

You're probably wondering: who the hell was David Attie?

My father was a steadily working commercial photographer for about 25 years. A student and protégé of famed art director Alexey Brodovitch – who had similarly mentored the careers of Richard Avedon and Irving Penn – his work appeared on magazine covers, book jackets, even subway posters throughout my childhood. He had gallery shows, published a beautiful book of photographs he took in the Soviet Union, and landed prints in the National Portrait Gallery. Then he passed away, in the early 1980s, a decade before the arrival of the internet. It wasn't long before he and his work had all but vanished.

I discovered this three years ago when, in a moment of procrastination from my own work as a TV writer, I Googled my father's name. Not much turned up. One thing that did was a blog post with two Pall Mall cigarette ads he'd drawn in the 1950s, when he was a commercial illustrator, followed by the cover of a trashy pulp novel he'd drawn around the same time, followed by this statement: "And for now, that's all we know about David Attie." So I posted a brief comment. I said that I was a direct relative, and that, actually, David Attie became a photographer and had a great career. I signed it "Eli".

Within a couple of days, I was contacted (on Twitter) by a guy named Brian Homer – a lovely man from Birmingham, who'd been influenced by my father's book Russian Self-Portraits and wanted to help get his work seen again. My first reaction: why hadn't I ever thought of that?

Weeks later, we met in New York, and along with my brother Oliver and my mother Dotty (a gifted, successful painter in her own right), spent a few days rifling through the dust-covered wooden boxes that contain my father's negatives – exactly as he had left them, in the Manhattan brownstone that was his home and studio, and where my mother still lives and works today.

Brian was interested in the Russian self- portraits, so that's what we organised. But I stumbled across something that interested me more: stunning studio portraits of the seminal roots-rock group The Band, at their peak in 1969, taken for the cover of Time magazine but never used. Being a bit of a rock obsessive, I decided to take the negatives home to Los Angeles, where I was sure I could get them published, exhibited and permanently enshrined in popular culture.

As it turned out, nobody cared that I had a few rolls of film by a long-dead photographer. Finally, a prominent rock photographer told me, "You need more pictures of famous people. That's the only way anyone's gonna care."

On my next trip to New York, I went back to the dust-covered wooden boxes, and found a small manila envelope labelled "Holiday, Capote, A3/58."

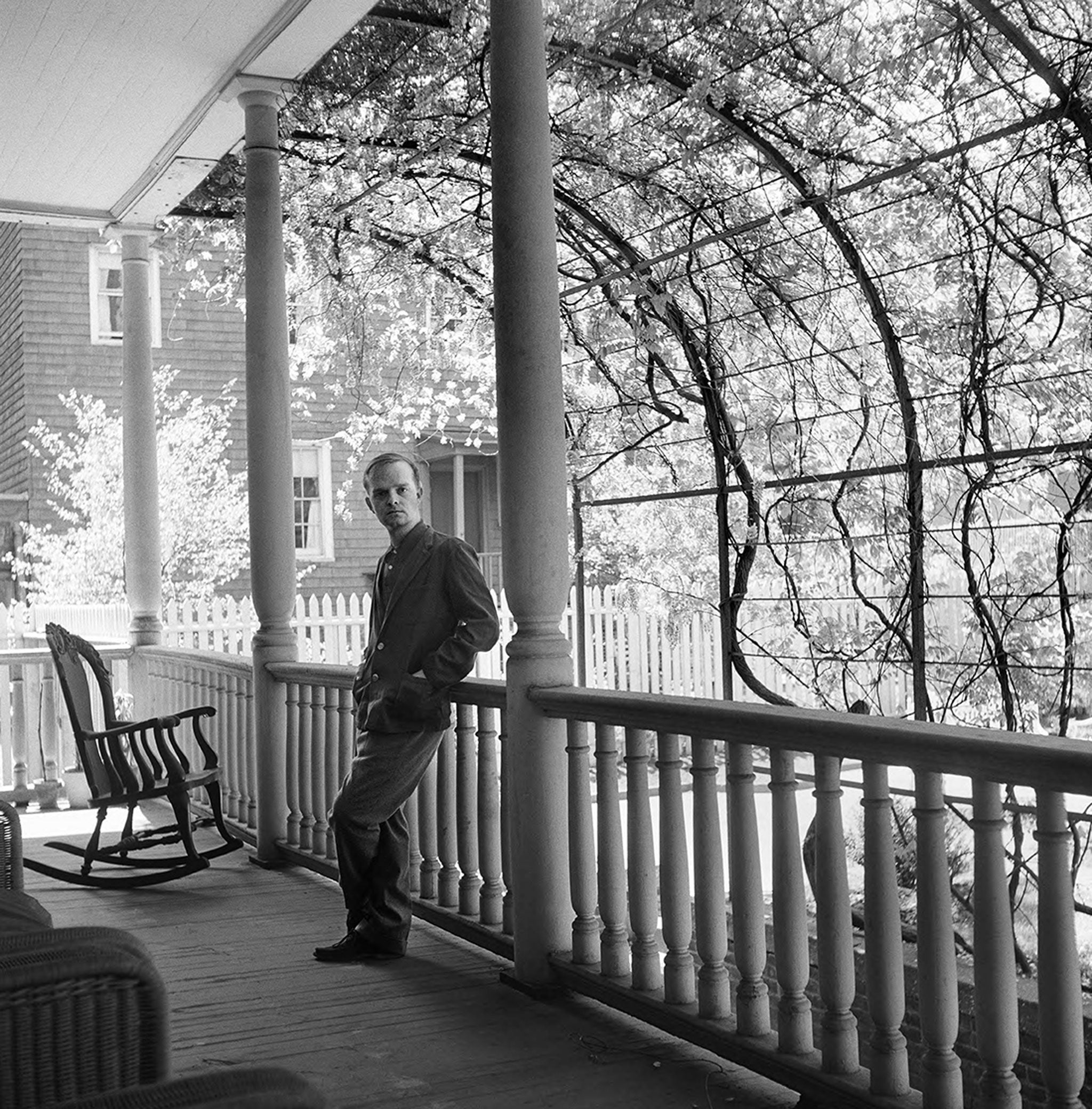

Now, I knew my father had photographed some notables – including the chess grand master Bobby Fischer and the composer Leonard Bernstein – but I had no idea he'd ever been near Capote. When I had the negatives printed, my jaw hit the floor. These were the coolest pictures of the author I'd ever seen. The still young, steely-eyed scribe looked like he was creating his own mythology right in front of the camera.

And thanks to the internet, my father's writings and my mother's recollections, I was able to piece together the story behind them.

By the late 1950s, my father's chosen career, commercial illustration, was dying fast; magazines and publishing houses were turning to photographs. He decided to make the switch, and signed up for Brodovitch's photography course at The New School (actually taught in Avedon's studio). Brodovitch, the longtime art director of Harper's Bazaar, is considered one of the fathers of modern magazine design; he's credited with inventing the two-page spread. He was also a brutally tough teacher.

One night, my father was developing film for his first class assignment, when he realised he'd overexposed every single frame. Class was the next day. In other words, he was toast—and so was his new career. In a panic, he started layering the negatives together, to create moody, impressionistic montages. His life must have been flashing before his eyes, and at the wrong exposure.

Brodovitch loved the montages, and offered my father his first professional assignment: to illustrate Breakfast at Tiffany's for its debut in Bazaar, with a series of his montages. Not bad for a first-timer. He worked around the clock for almost two months to complete the job.

Meanwhile, the Hearst Corporation, which published Bazaar, was having second thoughts about Tiffany's – which was, after all, a story about a woman who slept with men for money. The publisher wanted changes to the novella. Alice Morris, the fiction editor of Bazaar, said that while Capote initially refused, he relented "partly because I showed him the layouts… six pages with beautiful, atmospheric photographs".

Capote made all the changes, but Hearst told Bazaar not to run the novella anyway. Capote resold it to Esquire, where it flew off newsstands and made him a star – yet only a single image of my father's was used. In a letter I recently found, Capote upbraided Esquire for this, saying he'd made clear he "would not be interested [in reselling the novella] if you did not use Attie's [full series of] photographs". Could this early-career heartbreak have been the reason my father never spoke of Capote?

A couple of months later, Holiday magazine asked Capote to write the evocative essay "Brooklyn Heights: A Personal Memoir". k I can only guess that Capote himself recommended my father to illustrate it. Sometime in March 1958, they spent a day together. First, my father took portraits of Capote and some shots of his home on Willow Street. Then Capote showed him favourite haunts and local characters. My father spent another few days photographing the neighbourhood on his own. Their work ran in the February 1959 issue of Holiday. I managed to find a copy on eBay. To my amazement, Holiday used just four of the neighbourhood shots – and not a single picture of Capote himself.

When I learnt that the original Capote essay had been turned into a small book in 2002 – without any of my father's work – I sent an email to the publisher, The Little Bookroom. I suggested that my unseen shots of the very famous author might be useful for a second edition. And did I mention that he was famous?

I started to correspond with Little Bookroom publisher and editor Angela Hederman. She quickly decided to run a second edition, incorporating the Capote portraits. She also asked to see the neighbourhood shots. I scanned them, all 800, on a home-office scanner and barely even looked at them. A day or two later, she replied: "I think we have a photo book!"

Only then did I take a good look at the images and realised: hey, these are even better than pictures of famous people. The connection to Capote and the Brooklyn he describes would probably be enough to justify their resurrection. But there's also a tenderness to their point of view. This is mid-century street life captured by a guy who himself grew up on the streets of Brooklyn.

Friends have asked me if it's an emotional experience to look at these photographs, taken before my parents had even met. It's better than that. Because nothing is distilled, in the way that emotional experiences tend to be. As I look at frame after frame, I'm right there on the street with my dad, moving from block to block, lingering on what he likes, moving on from what he doesn't. It's a feeling of presence, not absence.

Perhaps the biggest thing I learnt is that while my father shied away from straight, documentary-style photography, he was great at it. He once wrote that he "never made peace with photography in its simplest expression. Because I started at a time when the great portraits by Penn, Avedon and Arnold Newman were being made, I did not wish to imitate that work." I know from my mother that he was also worried that he couldn't compete with those big names. In my view, he had no reason to be insecure.

What's most remarkable is that the story you've just read, and the book itself, represents just one week of work in my father's 25 -year career. Who knows what other stories are lurking in the rest of those dust-covered boxes?

'Brooklyn: A Personal Memoir by Truman Capote with the Lost Photographs of David Attie' (£19.99, The Little Bookroom) is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments