Thomas Schütte - Ahead of the rest

From huge bronzes to photographs of tiny clay faces, a new show of Thomas Schütte's work proves his mastery of the figurative, says Adrian Hamilton

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The German artist Thomas Schütte is arguably the finest figurative artist now working in Europe. Personally, I would drop the word "arguably". Although figurative art is alive and kicking, not least here in Britain (Thomas Houseago to name but one showing in London at the moment), none have managed to take monumental sculpture and intimate drawing and make it their own in quite the way Schütte has done.

Both the monumental and the intimate are on display at the Serpentine Gallery's exhibition. First, the sculpture. Even before you enter the Kensington Gardens gallery, on the grass outside, stand two of his well known Untitled Enemies series of 2011, gigantic bronzes of double figures entwined together in soulless agony. Held on tripod legs, they seem bodiless beneath their rope-wrapped cloaks, while the two bald and eyeless head look away from each other. What is extraordinary is not just the way that the artist expresses human tension in metal but the manner in which he makes the faces fleshy. They're a symbol of the hollowness of power but also its anger and its threat.

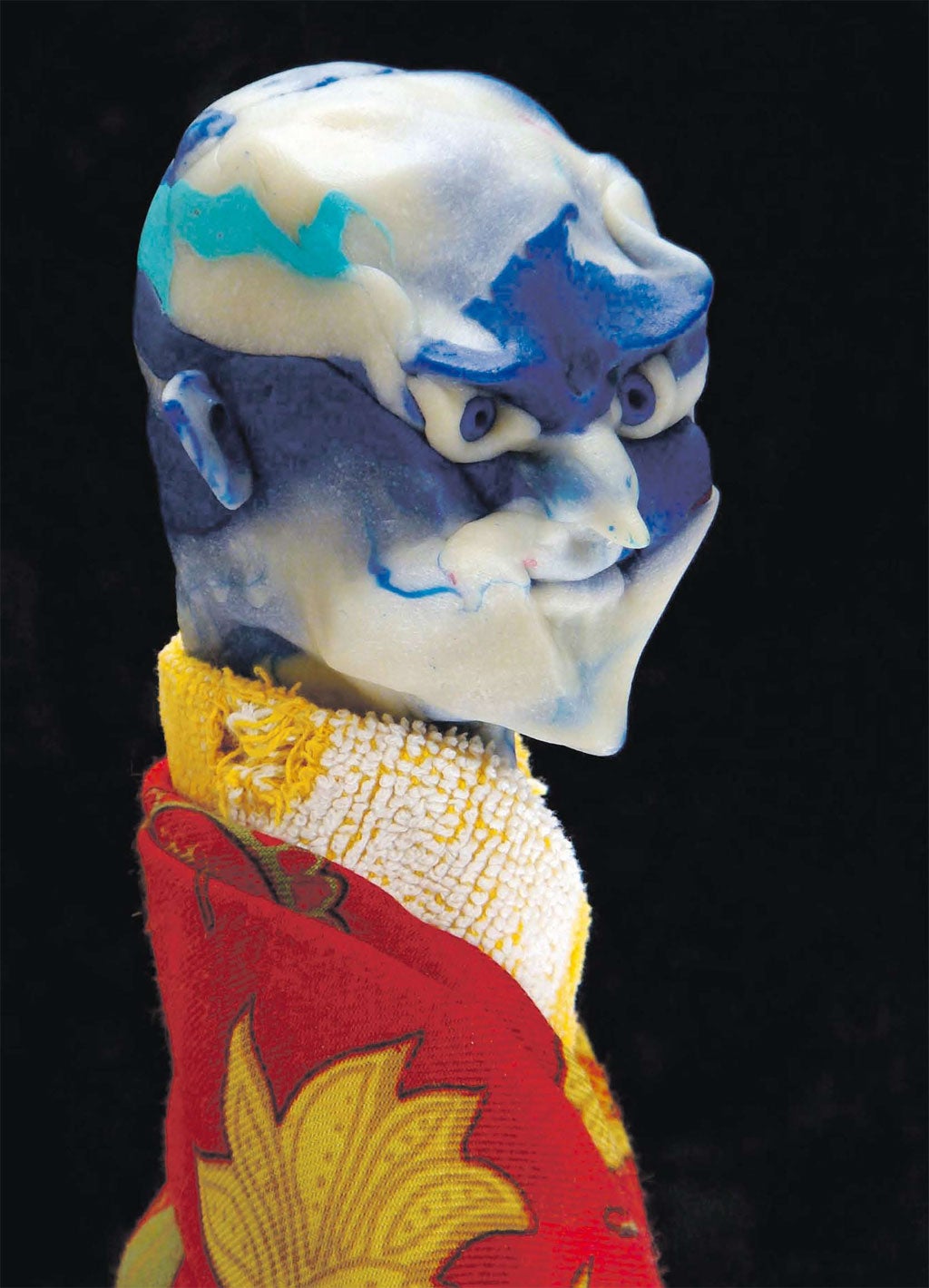

The same monumentality of scale and malleability of form is seen in the centrepiece of the show, Vater Staat (Father State). The figure stands nearly four metres tall in the central atrium, a colossus in steel breathing authority in its chiselled features, capped and begowned like a North African or Central Asian dictator. Only the steel is rusting and, when you walk around it, the gown seems bodiless beneath a head and shoulders held on a hidden structure. It's both terrifying and intriguing. Around it, quite opposite in scale but equally disturbing, are 30 close-up photographs of miniature faces modelled in clay, the Innocenti from 1994. Individually, they are human and even comic in their grimaces like children's finger face masks. Together they are unnerving, threatening in their mass.

Still in his forties, a product of the Dusseldorf Kunstakademie, Schütte is in one sense a very traditional artist. Although he has, particularly in his early career, worked a lot with architectural models and design, his central concern has always been with humanity and how to represent it. The Serpentine claims the show, titled Thomas Schütte: Faces and Figures as the first exhibition devoted solely to his portraiture. What comes through it is his deep commitment and knowledge of the genre.

The portrayal of power has long been part of the tradition of German art, but then so has the caricature of it through the exaggeration of features and facial gesture. Schütte has ascribed some of his inspiration from a visit to see the Roman portrait busts in the Capitoline Museum – realism made majestic. But his art also owes much to the 18th and 17th-century fascination with the extremes of emotion as seen in the face.

His modelled heads screech, scream, dribble, pout and purse. If the photographs of the Innocenti do it in miniature, the Wichte (translated here as "Jerks") do it naturally sized. Taking as his model the bronze portrait busts you see in town halls and public offices throughout Germany, he gives the series character through their individual modelling but vacuity through their eyeless looks. Arranged in line on wall plinths, glancing sideways, downwards, inwards but almost never at ease, they are a combined portrayal of the officials and middlemen who make authority and its excesses possible. Looking at them, one wonders again at the provincialness of so much of British art in its retreat to the personal and the showy.

In direct contrast are Schütte's drawings and watercolours. The modern portrait has never been the same since Cubism introduced multi-faced viewpoints and swept aside the old, fixed way of presenting snapshot of character and position. Schütte's answer is to accept the limitations of the fixed-point portrait but to do them in series, capturing different moods and looks in varied media and brushwork. The framed watercolours and drawings with engraved line are, in one sense, quite conventional. They are also surprising in their delicacy of line and sensibility. An early self-portrait done in oil on cotton from 1975 builds up the image precisely, using a grid that shows through the paint. The portrait is of the artist as he would wish to be but caught with a knowingness that subverts any sentimentality.

He does the same with a fluid and penetrating series of self-portraits, the Mirror Drawings from two decades later. Hung across a whole wall, the face is observed in a roundel as if in a focusing lens. The eyes are fully open, the glance questioning, the face occasionally coloured. It's as if other painters such as Rembrandt are looking out at you and are telling you what they are about (or would like to be). In these you are the artist as observer, outside himself and by no means admiring.

His Luise series from the same period in the mid-Nineties are more openly affectionate. The girl's eyes never engage as they look down or sidewise. The graphic line is purposeful and confident, the impression disengaged but open. So, too, with his recent portraits of his daughter and friends. It's amazing how the modern macho artist weakens at the knee when it comes to their offspring. Schütte is no exception but by using ink with watercolours, he gets away with it.

He is least successful when he tries to marry the intimate with the monumental in his female heads, such as the four-foot sculpture of Walser's Wife made in lacquer applied on aluminium. You see the references, the serene look and glance of the Thai Buddhas, the rough of the hair against the fine-boned face but in the end, the head, like the Frauenkopf in patinated bronze, also on show, it remains more interesting in its material than its message.

Fortunately, there's enough humour around to leaven the load. A delightful watercolour drawing of Adolf duck has a Hitler's moustache and a swastika added to a rubber duck while a picture of Me? draws himself as a preening swan. When commissioned to fill the fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square, he produced a deliberately glamorous Hotel for Birds. A joke, yes, but with purpose. If any artist can get a grip on today's troubled and fractious world it is Schütte.

'Thomas Schütte: Faces and Figures'. Serpentine Gallery, W2. To 18 November. The artist's most recent works are on show at the Frith Street Gallery, W1 until 15 November

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments