The Brazil series by Bob Dylan: New series of paintings suggests he shouldn't give up day job

As a painter, Dylan makes a fine singer-songwriter

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Last week a new exhibition of hand-signed, limited-edition prints based on recent paintings by Bob Dylan went on sale in a gallery in Mayfair. As far as subject matter is concerned, this is a new departure for one of life’s eternal ramblers.

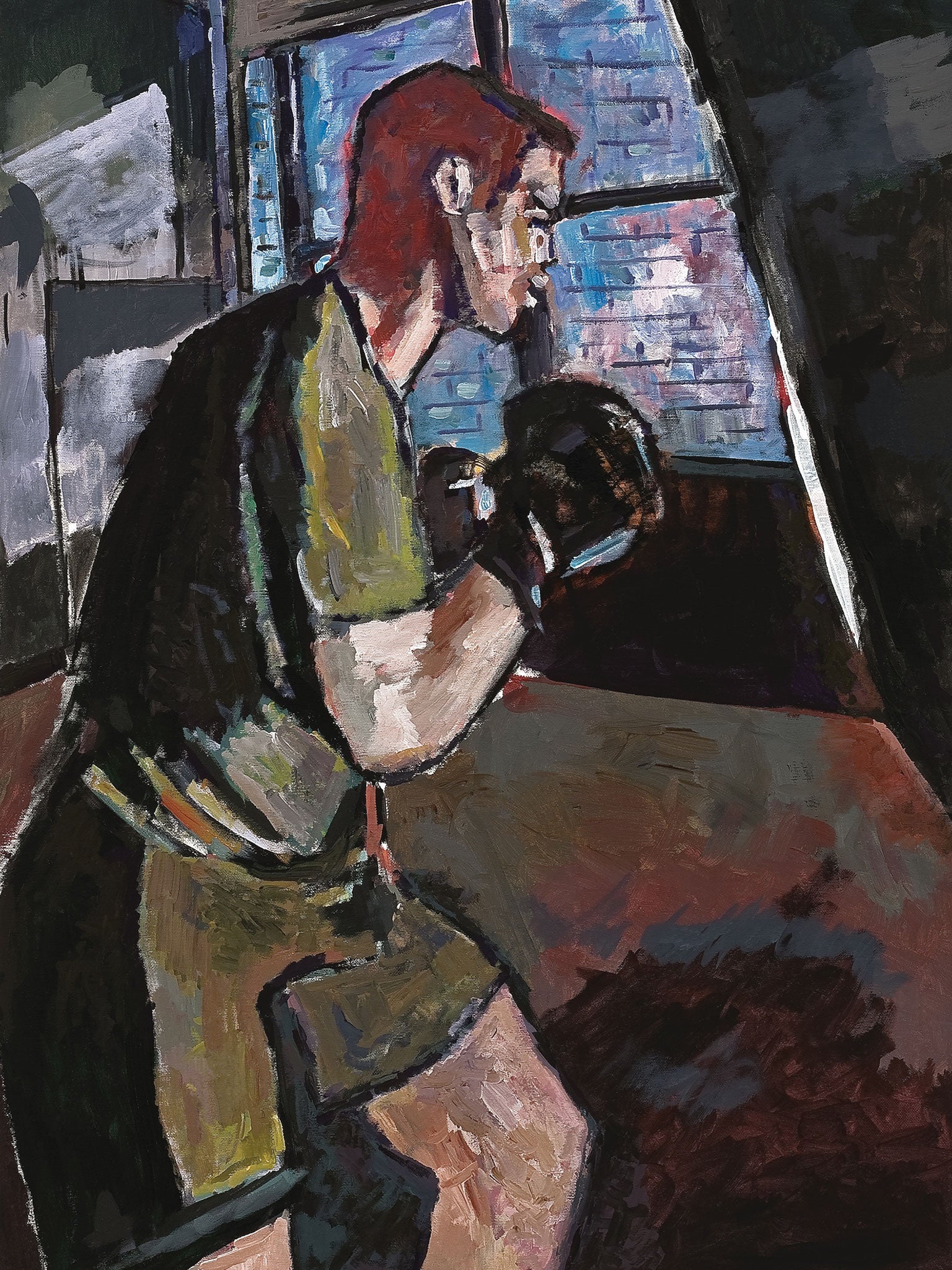

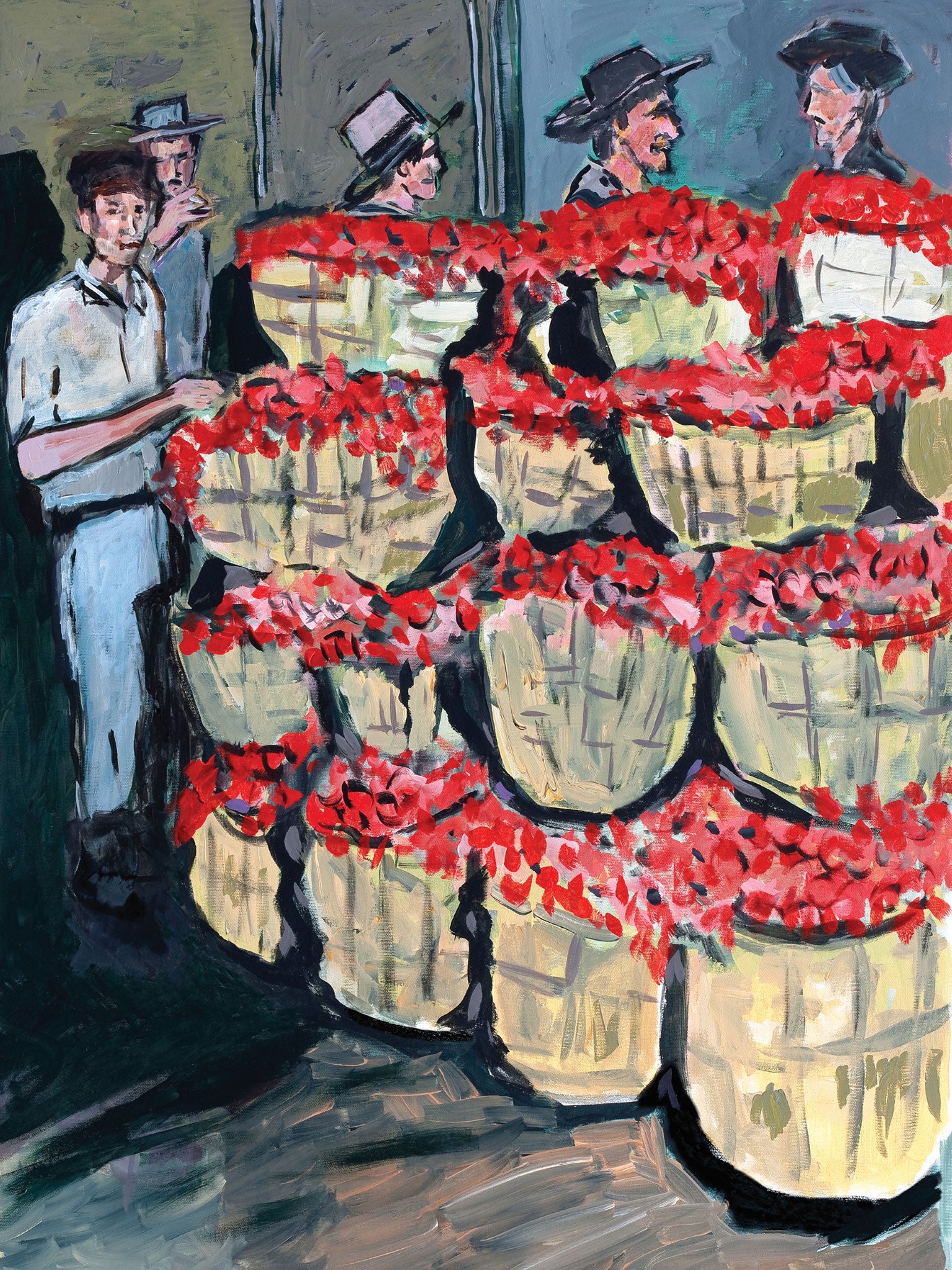

The Brazil Series chronicles Dylan’s engagement with a country he has often visited, but it is not a familiar view of the place by any means. This is Brazil seen through its nooks and corners, from the level of the street. There are no beaches here, no heart-rending representations of the rape of Amazonia, no fiesta mood. These are down-to-earth, bare-knuckle encounters: a view of a peopleless favela with its ramshackle cram of gimcrack human habitations, all dusty browns and ochres, teeming down a hillside, with the shabby pageantry of washing hung out on a line, a criss-crossing of telegraph wires, and a raging stream crossed by a single-plank bridge; ranchers in profile with their stetsons cocked back from their faces; and a boxer (shades of Hurricane Carter here) sparring with his destiny in a darkened ring.

The best of these is Favela Villa Broncos. The space of the painting feels tight-squeezed. The colours are a patchwork of finely worked gradations. The absence of any human presence gives the image an aura of desolation. The least successful of the three is Boxing Gym. The colour lies flat and inert against the human body. Dylan has tried to use colour in combination with form experimentally here, but the result is only woodenness. The way that colour has been smearily laid over the sketchy, cartoony profiles of The Ranchers is as sensitive and successful as a fistful of flung custard pie.

Bob Dylan the visual artist only went on public view in 2008, by which time he was a long way through his seventh decade. He had been drawing – and even painting – for a long time, from the 1960s onwards, and in the preface to a book of his paintings published in that year, he tried to explain what had compelled him to do it in the first place, why the distraction of art had also been a kind of solace to him: “So that if you were at a loss for words,” he wrote, “something could be explained and, even more importantly, not misunderstood. Rather than fantasise, be real and draw it only if it is in front of you and if it’s not there, put it there and by making the lines connect, we can vaguely get something other than the world we know.”

When you are living through those times between times, between concerts say, you need something other than words to express your view of life’s strange passing frieze. We first saw Dylan’s art, intermittently, on album sleeves, during the 1970s – the moon-faced album cover to Self-Portrait and the sheaf of three rather Munch-like heads swimming into view on Planet Waves, were both painted by him, for example – and then it went underground for decades.

Dylan’s art is the work of a perpetual itinerant who is catching life on the wing as it fizzes and drizzles by. He is the eternal outsider looking in with a mixture of dispassion and curiosity. And the quality of the work is very variable. Some of these images are no better than the efforts of any two-bit pavement street artist praying to Lady Luck, trying to earn a dollar or two. Then, as if by some miraculous throw of the dice, he can raise his game and give us an enduring image of train tracks receding, and it not only haunts us by presenting itself as a kind of summation of the American dream, but it also seems to sum up the trajectory of the man himself. There is blood on those tracks.

It had all begun after he made that journey from Hibbing, Minnesota, down to New York City, in the early 1960s, a journey which would cause him to make himself anew – a new name and a new identity as the ever shape-shfting, freewheeling song-and-dance man. In those first drawings the eye battened down on simple things, as he described it in his memoir Chronicles in 2004: “What would I draw? Well, I guess I would start with whatever was at hand. I sat at the table, took out a pencil and paper and drew the typewriter, a crucifix, a rose, pencils and knives and pins, empty cigarette boxes. I’d lose track of time completely. An hour or two could go by and it would seem like only a minute. Not that I thought that I was any great drawer, but I did feel like I was putting an orderliness to the chaos around... In a strange way I noticed that it purified the experience of my eye, and I would make drawings of my own for years to come.”

And that is much how it has continued to this day. None of this work is staged. What he sees in front of his eyes, day by day, is what he paints or draws. It is the everyday things that engage him – a truck stop, a woman with her back to you at a bar, a cycle biding its time against a tree, all laid down with an unfussy simplicity of means, often colour laid down on top of line drawings. Anyone who caught Mood Swings, his very first show of sculpture fabricated in iron, exhibited in London in 2013, would have found stark proof of the kinds of objects that really resonate with him. The pieces he made were all assemblages, and these assemblages consisted of useful things plucked from any proud workingman’s tool box: a wrench, a spanner, a cog, a chain. Simple, honest, durable tools for wresting order from chaos.

The most important question is this, of course. Does Bob Dylan, have any real skills as a painter? Only intermittently. His art always possesses a verve and a kind of brash immediacy – like so much folk art the world over. It is also technically pretty crude, often suspended somewhere between cartoon and caricature, in spite of the fact that there is plenty of evidence here that he has looked at and learnt from a lot of art by other people, from Degas to Van Gogh, from Soutine to Matisse and the experimental art that came out of Russia in the second decade of the 20th century before it was crushed by the forces of counter-revolution. Most of all, you can see behind it, everywhere, the ghostly presence of his early hero, Woody Guthrie, who illustrated his own autobiography Bound for Glory with powerful line drawings of working people going about their daily business of hard survival that Dylan seems to be inwardly urging himself to emulate again and again. It is ornery, wilfully of itself, in a characteristically cussed Dylan fashion.

As he once wrote: ‘Sometimes you just want to do things your way, want to see for yourself what lies behind the misty curtain.’ Unfortunately, cussedness and dogged self-belief will only take you so far along the road.

The Brazil Series by Bob Dylan is on display at Castle Fine Art, 42 South Molton Street, London, until 30 May; castlegalleries.com

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments