The Big Question: Why have leading cultural figures declared war on the Arts Council?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Why are we asking this now?

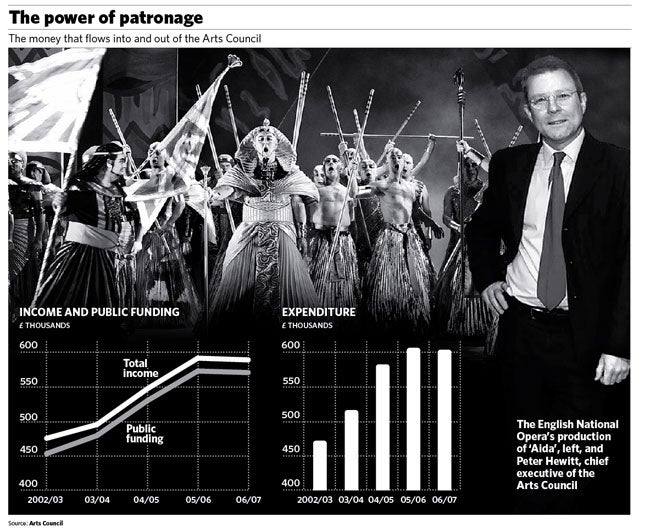

The Arts Council, the quango that funds the bulk of the country's artistic activity, has announced that it is ceasing to fund nearly a quarter of the organisations that it currently finances – 194 of them, ranging from theatres such as the Northcott in Exeter to orchestras such as the City of London Sinfonia to art galleries, literary groups, gay arts groups, and the National Student Drama Festival. Many of those taking a cut will have to close down. Meanwhile, other organisations, favoured by the Arts Council, will receive sizeable increases.

This week a meeting of theatre worthies including famous names such as Sir Ian McKellen, Kevin Spacey and Joanna Lumley passed a motion of no confidence in the Arts Council. Sir Ian said the cuts were "destructive, disturbing and distasteful". Ms Lumley said: "If regional theatres are going wrong, let's make them right. Don't just shut them down."

Isn't the Arts Council merely passing on government cuts?

No. Ironically, the Arts Council's own funds are pretty healthy after the Treasury gave a larger than expected increase to the arts in the most recent Public Spending Review. This is not a matter of penny-pinching because the funds are not there. It is a clear policy decision to "fund fewer better", a policy the Arts Council has been toying with for about 15 years now, and it has finally decided to bite the bullet.

Isn't that unfair?

Not necessarily? Though the most vociferous members of the arts world would have you believe it is tantamount to cultural vandalism, there is a case to say that companies can grow complacent and unwilling to experiment if they know that they are guaranteed funding. It has also been the case that companies set up by legendary figures in the arts continue to be funded long after those inspirational figures have departed.

What has the McMaster Report got to do with all this?

The McMaster Report, published yesterday and overseen by Sir Brian McMaster, the former Director of the Edinburgh International Festival, called for ways to increase excellence in the arts rather than concentrating on targets. But the Arts Council grant announcements are separate from the McMaster report, which has at long last called for a move away from the New Labour obsession with targets in the arts (numbers of ethnic minorities visiting museums etc) in favour of encouraging good work, and being unafraid of charges of elitism.

This is very much the wish of the current Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport, James Purnell, and it would be putting too much faith in coincidence to think that the Arts Council just happened to change its philosophy at the same time as the McMaster report came out.

Mr Purnell summed up his philosophy this week: "The 'I am funded, therefore I am' argument has to be overhauled... We have to dump crude targets and give artists and arts companies a new freedom. A freedom to experiment and take risks."

So should we be applauding the Arts Council?

No, because in their usual opaque, enigmatic and unaccountable way, they seem to have chosen some very rum examples. Londoners know that the Bush Theatre, for example, is a hugely interesting and influential centre of new writing. But that faces closure because of the cuts. The Northcott Theatre in Exeter will leave theatregoers in its catchment area with no real alternative if it too has to close. The National Student Drama Festival, which gave a first showcase to Simon Russell Beale and many other star names, uniquely gives a first taste of theatre to the nation's young: both on and behind the stage and in the audiences. The rationale given by the Council's chief executive, Peter Hewitt, left much to be guessed at. He said: "Sometimes this is on the grounds of their performance to date, and sometimes it is because we think the money can be used more effectively elsewhere."

Aren't there grounds for singling out certain organisations?

Who knows? Its meetings are secret, its press conferences rare. It has a culture of unaccountability. When the Arts Minister is asked in Parliament about funding of organisations, he will usually reply: "That is a matter for the Arts Council." But because the Council meets in private, we never get to know its reasoning.

Then why do we have an Arts Council?

That's the $64,000 question. And increasingly it's a relevant one. The Arts Council was set up in 1946 to distribute government money to the arts, a visible sign of the much vaunted "arm's length principle" which kept the government away from directly funding cultural activity, lest it interfere. The arm's length principle still has the status of holy writ in the arts world. But does it really make much sense? There is no arm's length principle in health or education, where the elected government of the day is charged with running the system. One former arts minister said in desperation: "This is crazy. I spend three months negotiating with the Treasury to get money for the arts, then nine months watching it being spent and being unable to have any say in it." The Government funds the national museums and galleries directly, but there is no record of it trying to interfere with what the Tate puts on its walls. Is it really a genuine fear that it would interfere with what the National Theatre puts on its stages?

Funding aside, does the Arts Councildo a good job?

It has proved astonishingly ineffective in coping with recent crises in the arts. The English National Opera, for example, has lurched from problem to problem in the last few years, with frequent changes of management. But the Arts Council has distanced itself. Ditto, the Bristol Old Vic, which has been forced to close.

So should the Government take over running the arts?

There's a strong case for it – and for the abolition of the Arts Council. Then at least the voters of Exeter and Bristol and elsewhere would be able to make their feelings known in the normal democratic way, with their MPs and through the ballot box, rather than being subject to the unexplained decrees of an unelected quango. The Arts Council's pursuit of excellence and its determination to fund fewer better is not wrong in itself; but in the choices it has made, and in its alienation of much of the arts world, it may have hastened its own demise.

So is the Arts Council turning elitist?

Yes...

* It is earmarking and generously funding a smaller number of arts companies, which it has decided epitomise excellence

* None of the famous names flagship companies in London that it funds is on the cuts list

* It seems no longer to see as a priority the increase in audiences from ethnic minorities

No...

* There is nothing elitist about excellence. Artistic quality inspires people from every class

* There is nothing elitist about giving more money to organisations that are performing well

* Previous efforts to gear artistic activity to increasing audiences from various minorities were loathed across the arts community

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments