Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

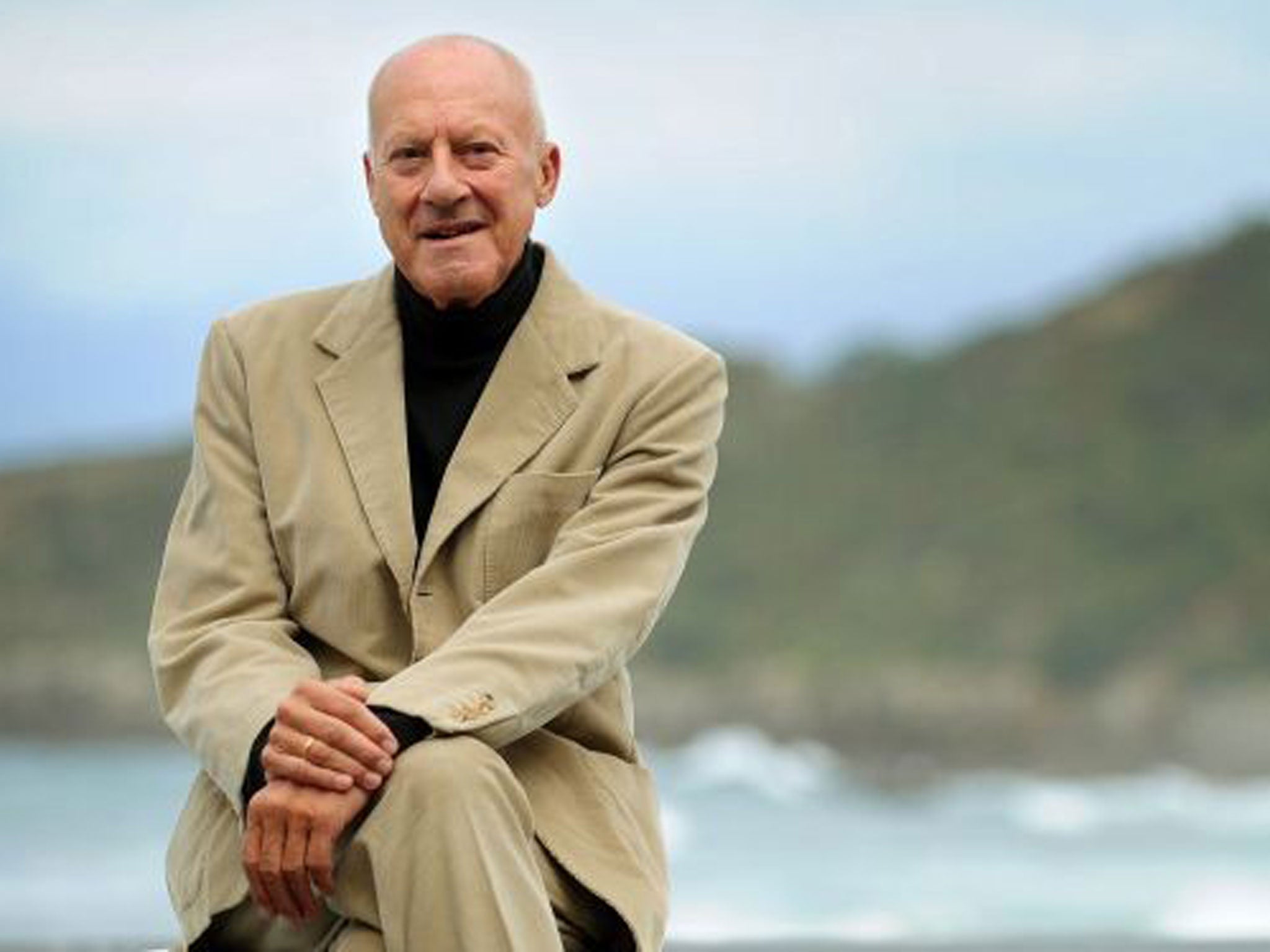

Your support makes all the difference.The world's most famous architect, Norman Foster, 77, designed the Carré d'Art in Nîmes, France, more than 20 years ago. Now he's about to curate his first art show in it, largely made up of works by the artists he collects.

For the first time, and in considerable detail, we are about to glimpse a side of him that has nothing to do with architectural efficiencies or iconic design, and everything to do with his emotional and intellectual hinterland.

Until about 1990, emotion was not a word that one could easily associate with Foster. Buildings such as the swerving, darkly glassed Willis Faber office in Ipswich, the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts in Norwich, the Hong Kong & Shanghai Bank headquarters, and Stansted Airport radiated powerful auras of technical precision.

Foster's interest in art surfaced quite early on. He bought a Constructivist artwork by Simon Nicholson in the early 1960s, and when he opened his first practice in Covent Garden in 1967, he hung a Marc Vaux canvas in the reception. His interest in art has been an increasingly significant part of his life since his marriage, in 1996, to Elena Ochoa. The first artwork that Norman and Elena Foster bought together was Andy Warhol's big canvas, Lenin, in 1995.

“My wife and I live with art,” explains Foster. “It reflects our tastes, our intuitions, so we also have work by relatively unknown artists – mostly abstract, in the pure sense, or abstractions of the human figure. Abstraction is associated with the birth of Modernism, but it goes back 23,000 years to primitive art.”

“The only reason Elena and I would acquire an artwork is if it moves us emotionally or intellectually. I don't feel able to judge or criticise art.”

It was never the Fosters' intention to create a personal art collection. Before they met, they only displayed the occasional painting or sculpture, mostly by artist friends. The difference now, says Foster, is that all of their domestic spaces are saturated by the contributions of diverse artists across several generations.

Thus, chez Foster, you can find an abstract by the young Berlin painter Daniel Lergon next to a sculpture by Alberto Giacometti, next to a portrait by Francis Picabia: “We do not have to offer an explanation to anyone.”

Moving, Norman Foster on Art, Carré d'Art Museum of Contemporary Art, Nîmes, France, 3 May to 15 September

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments