Sarah Lucas: A Young British Artist grows up and speaks out

These days, Sarah Lucas has no time for her old crowd's egocentricity – but as her retrospective opens, she's ready to talk sex, death, and her loathing of celebrity

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

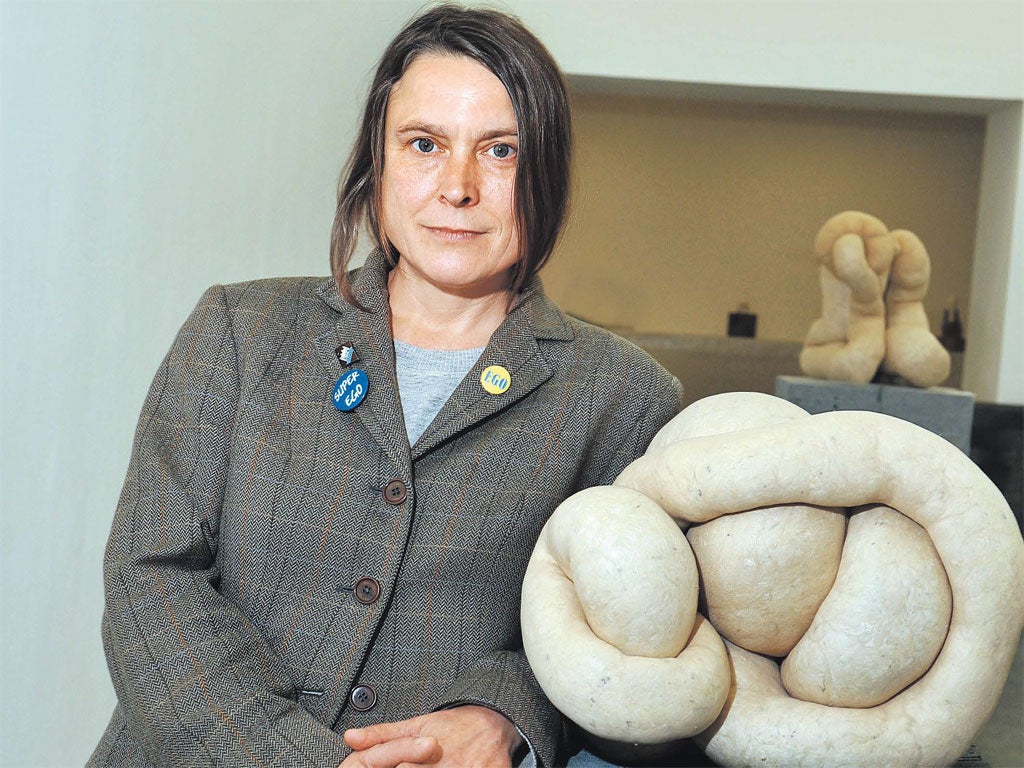

Your support makes all the difference.Sarah Lucas is wearing a badge saying "ego". It is, I can't help thinking when I bump into her in the loo, and pretend I don't know who she is, ironic. It's ironic because, in a generation of artists known for the size of their egos, she's probably the one who's known for it least. She is also, according to its self-selected leader, the best. She is, says Damien Hirst, who has bought back a fair bit of her early work from Charles Saatchi, "out there stripped to the mast like Turner in the storm, making excellent pieces over and over again".

Sarah Lucas laughs when I ask her about the badge she's wearing, on a baggy tweed jacket, and says she's wearing it because she "likes it". She looks like someone who wears what she wants. In the photos she put in her exhibitions when she really was what she'll always be called, which is a Young British Artist, she often looked, as Damien Hirst also said, like a "bloke". In the doorway of the shop in the East End she had for six months with Tracey Emin, or standing in front of a brick wall with a giant fish, or sitting on a floor behind a skull, or puffing away, as she almost always seemed to, on a fag, she looked, in her big jackets, big jeans and big boots, as if she was trying quite hard to look like a man.

But she's much thinner than I expected, and, in spite of the lack of make-up, and the lanky hair, and flash of gold where there should be teeth, more feminine. "I think," says Lucas, when I tell her this, "I did used to look bigger, but I think people photograph bigger, and I photograph more masculine as well." She didn't like it at first, but then decided to use it. "Instead of thinking 'I hate the way I look in that photo,'" she explains, "I could think 'that's good'. She has, she says, "never been someone for make-up". She has, in fact, had "fun" not "using her femininity" because "people find it so odd". At the Groucho club, where the YBAs used to hang out, she'd stare at the women "in their summer dresses and perfume, flirting with men", and enjoy the fact that she wasn't. "You realise," she says, "that you've got some other charisma."

You can say that again. It's quite rare to meet a heterosexual woman who's making no attempt at all to make herself attractive to men, but who – how shall I put this? – radiates sex. But it's also quite hard to think of an artist whose work is so much about it. You think of it as soon as you walk past the giant concrete courgettes by the entrance to the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds, where this exhibition, called Ordinary Things, is being put up. You think of it when you see the old mattress slumped against the wall, which Lucas found in a junk shop in Berlin four years before Tracey Emin took a stained mattress and called it "My bed", and when you see the melons nestling in pouches on it, and the open bucket underneath them, and the oranges next to the cucumber that's stuck out at an angle, pointing up.

You think of it when you see the stuffed tights stretched and bent into sausagey shapes on breeze blocks that serve as plinths. You see the mottled surface that makes you think of flesh, and cellulite, and thread veins, and you can't help thinking of probing fingers and legs wrapped around legs. You see a knobbly white shape rising out of a hunk of wood and you wonder what it's doing on top of a piece of wood, but you don't, for one moment, wonder what it's meant to represent. You see stuffed tights, dyed black, and linked up to make a spider, but what you think of isn't, after the first glance, a spider. What you think of, when you see the spider, and the long fluorescent light bulb propped between a pair of concrete boots, and the concrete gourd, and the concrete marrow, is sex.

And when you see a pair of tights stuffed with kapok, wearing, if tights can wear things, blue nylon hold-ups, splayed on a chair, with more stuffed tights rising up from the top of the gusset, and flopping over, you don't just think of sex. What you do is blush. You didn't think a pair of stuffed tights could actually make you blush, but now, you realise, as you feel the heat in your cheeks, they can.

This is what Sarah Lucas does. She takes, as the title of this exhibition of her sculpture suggests, "ordinary things", like tights, or vegetables, or an old mattress, or bits of wood, or tables, or eggs, or kebabs, or boots, or concrete casts of boots, and she does something to them that can actually make you blush. She doesn't just take ordinary objects and say they're art. Quite a lot of the YBAs, and the people they have influenced, do. They seem to think that if you say something's art it's art, and if you say something's shocking, it is. They seem to forget that the person to decide whether something's shocking, or powerful, or moving, isn't the person who made it.

"I always think it's nice to have electricity in something, a spark," says Lucas, as we wander over to the corner where her work, "Unknown Soldier" is being set up. She's talking about literal electricity – in this case a strip light – but she's also, of course, talking about the artistic process. This piece, like quite a few of her pieces, including her most recent one, which she's called "Jubilee", involves a pair of concrete boots. But something happens to the boots in the process that turns them, or seems to turn them, into something else. Is this a kind of alchemy? And how does she know she's got there? Lucas stares at the boots for a moment before replying. "There's just a moment when it comes together and you think 'that's it, it doesn't need more than that, it doesn't need less'." When she put the first pair of stuffed tights on a chair (which later became the first of a series of pieces she called "Bunny") she too blushed. "The embarrassment factor can be quite important," she says, "because then you know you've touched a nerve, even with yourself."

It starts, she says, with "playing around". She has never had a studio, and uses things she finds lying around the house, or in the shed. "It's not really a thinking thing for me," she says, "it's really my hands doing it more than my head." The "thinking part", she says, is more in the titles. Which tend to make the sexual intent pretty clear. "Tree Nob", for example, doesn't require too much explanation, even if it is a bit unusual to have a "nob" or "knob" (and particularly a "knob" based on plaster casts of your boyfriend's penis) sitting on a tree trunk. Nor does "Man Marrow". Not quite so obvious is "Au Naturel" for the mattress with the melons and cucumber, or "The King", for painted branches suspended from the ceiling in the shape of a wheel. But "Nud", for the sausagey stuffed tights that look like flesh, seems just right. A made-up word for a made-up thing that makes you think of a nude, but isn't.

The first "Nud" – she's now done "loads of them" – came about when her partner, the artist Julian Simmonds, found some old tights in the shed. Once she'd stuffed them with kapok, and twisted them into shape, she had a "eureka moment." Nuds, she says, "have made such an impression on people. It's amazing," she says, "when you're doing that crumpling up thing, why some are better than others. You can only know when you see it. Whether that falls into being naff, or too cartoony".

When she talks about her work, she's unusually matter of fact. She was surprised, she says, by the success of works like "Two Fried Eggs and a Kebab", which, as you might guess, involved two fried eggs (freshly made each day) and (freshly bought each day) a kebab. She showed it in a temporary space in Soho in 1992, at the same time as her first exhibition, called (yes, really) "Penis Nailed to a Board". But she didn't, she says, want to be "the eggs person" or "the tights person". "I suppose," she says, "I took very seriously the idea of art being unique."

Unique, I tell her, is aiming quite high. Even unusual is aiming quite high. Does she think she is original? I expect her to bat this away, but she doesn't. "I think so." And then, perhaps thinking she's being too self-deprecatingly feminine: "Yes. I suppose I do."

She wasn't, she tells me over a sandwich and a bottle of wine, "one of these people who wanted to be an artist". Her father was a milkman. Her mother was a cleaner. Home was a council flat off the Holloway Road. "My mum wouldn't let us do any homework," she says. "She said 'well, you're there all week, that should be enough'." So Lucas didn't. She left school at 16, "bummed around for a couple of years" and "did a lot of hitchhiking around Europe in a very cheap way". It was while she was doing a temporary job working with children that someone suggested she do an art evening class. She did one, at the Working Men's College, and then got into the London College of Printing to do a foundation course, and then went on to Goldsmith's College to do a degree in fine art.

She was a year ahead of Gary Hume and Michael Landy, three years ahead of Sam Taylor-Wood and Gillian Wearing and two years ahead of Matt Collishaw, Angus Fairhurst and a young artist called Damien Hirst. It was, she says, a "very exciting" time, but it was only after she graduated, when Hirst and others organised an exhibition called Freeze, in a warehouse in Docklands, that she realised she was part of something much bigger. "I suppose," she says, "it was at that moment that I realised art is actually contemporary. You always think art history is in the past, and suddenly it was now."

Freeze (in 1988) was followed, in 1990, by The East Country Yard Show, and then by a series of exhibitions called "Young British Art" organised by an ad man called Charles Saatchi. He didn't just exhibit art. He bought it, too. Suddenly, the whole thing wasn't just about fashion, or excitement. It was also about money.

"Damien would say he had no plan," says Lucas, between bites of her sandwich, "but he always seems to me to somehow have had an instinct for that side of it. Not just the business, but the seeing how these things work. I don't," she adds, "think I did". She has talked, I remind her, about Damien Hirst and Tracey Emin "realising the value of being a brat". For all her hard partying – the writer Gordon Burn once called her "the most unabashedly, balls-out rock *'roll" of the bunch – she never seems to have been one. Does she ever regret it?

"There have," she says, "been times in my life when I've thought maybe that's a weakness, a sort of cowardliness, not to be more brattish, but I think you're either like that, or not. Of course I'm always talked about, or our generation, in terms of the art equivalent of punks, and I've never considered myself a punk at all. But that doesn't," she says, with the honesty that makes a conversation with her feel like a proper conversation, "mean that I haven't benefited from that brattishness."

And what about celebrity? Sensation, the Saatchi exhibition that introduced the YBAs to a wider British public, was on at the Royal Academy in 1997, which is the same year Big Brother made a nation start to want to be famous for being famous. Was there a point when she felt that the celebrity was overtaking the art? Lucas nods. "That's something I did decide to avoid by being in Suffolk and just opting out of it. I was never that comfortable with the celebrity side of it." She did, it's true, move to Suffolk, to live in Benjamin Britten's house (which, for a while, she used as a weekend retreat) but that was only five years ago, and well after the YBA hysteria had died down. But she did, she says, stop reading newspapers and art magazines years ago. "I'm so out of touch with it now," she says, "that I really don't know what's going on. Maybe," she adds, with another flash of that fierce honesty, "I'm just avoiding something for the sake of it, and having a trivial life."

So doesn't she keep up with the news? And doesn't she feel an artist should? For a moment, she looks confused. "I started to hate the news," she says, "and the tone it's delivered in. But if you don't watch it,it's not there. Your life isn't full of these marauding rapists and stuff." But I'm not, I tell her, talking about rapists. I'm talking about things like the biggest global economic crisis since the 1930s. Doesn't she think artists should engage with things like that?

"I've had my ups and downs with it," she says. "Unknown Soldier" (the concrete boots with the strip light) was, she says, a response to the Iraq war. If it was, its main message (if art ever has a message) seems to be that soldiers like sex. She thinks, she says, when I try to push her further on politics, that the government "could get rid of advertising". When I ask how this would work in a market society, she's vague. "Society's about what should be working for us," she says, "not the other way round."

Well, yes. But the market has worked for the YBAs, and it has certainly worked for her. Is she happy with the balance of money and art in her life? For the first time, she almost looks coy. "Mmm, yes," she says, drumming her fingers on the table. "Very, actually. That wasn't something I imagined. I thought I was sacrificing material gains for something I really wanted to do." And does she ever feel guilty about her success? She wraps her fingers round her chin. "Oh yes," she says. "But I'm trying to dispense with that a bit." Why? "Because," she says, with an intensity that takes me by surprise, "it doesn't help."

Nearly all her partners have been artists, and she has been more successful than them all. Most of her friends have been artists, too. She met Tracey Emin at her first show, and a "tempestuous" friendship was born. For the six months they ran a shop together (selling wire penises and T-shirts with very rude slogans) they were hardly apart. "Tracey likes a lot of drama," says Lucas, "which I don't really, so it was all a bit of a mismatch. But that was what worked about it as well". And was it ever sexual? Lucas smiles. "No. It could have gone the other way, I suppose. I think Tracey would have wanted it to go more the other way than me. I found her too possessive. She sort of gets her claws in. There was enough for me without that."

Tracey Emin has made herself the focus of her work. She has, for example, made a lot of work about the fact that she has had several abortions and is childless, at 49. Sarah Lucas had an abortion at 17 and is also childless at 49. Was she ever tempted to put more of herself in her work? "No. I think it's a bit second-rate, really, to exploit all that personal stuff." So is she saying she thinks Tracey Emin's work is second-rate? Lucas looks down at her hands and then back at me. "Yes," she says, "I suppose I am". And Damien Hirst's? "I don't," she says, "like his work much either."

If Sarah Lucas did make work about herself, there'd be a lot of sadness in her work, too. Her ex-boyfriend, Angus Fairhurst, hanged himself in 2008. She is, she says, still living with the grief. She also struggles with depression. "I sink like a stone," she says, "but the next minute I'm out of it. I think it's best to keep busy". She has, I remind her, talked about art as "maintaining a certain energy". Is that also her philosophy of life? "Mmm," she says, stroking her cheek, "I was actually talking about artworks, but I think it does apply to life as well."

I think of the courgettes, and the melons, and the orange, and the tights. I look at this woman who wears what she wants, and says what she wants, and makes the art she wants, and who doesn't seem to give a flying fig (or orange, or melon) what other people think. So that, I say, is why there's so much sex. There's death, too, because there's always death too, but sex is what you set against it. "It's the spark," says Lucas. "It's the divine spark."

And is that, I ask, why you see sex everywhere? Because the challenge is to find the life? "Yes," says Sarah Lucas, and we both take another gulp of wine. "Yes, life is the living. That's Damien's phrase," she says, "but life is the living. Yes."

Ordinary Things, Henry Moore Institute, Leeds (henry-moore.org) to 21 October

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments