From coating council flats in crystals to burying aeroplanes: Meet artist Roger Hiorns

As a new exhibition of paintings depicting gay sex opens at Corvi-Mora gallery, the artist explains he why isn't interested in fame, money or repeating himself

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Last year, the artist Roger Hiorns received an email from a preacher at an evangelical Christian church in Abuja, Nigeria, curious about why Hiorns had buried an aeroplane.

He had read how the artist buried a fighter jet in the grounds of a laser laboratory in Prague, and he was thinking about doing the same. He felt that the ceremony might add to the connection between him and his congregation.

Hiorns could not have been more pleased: “It might seem insane but that makes it interesting. It suggests to me there is a need for it. Being an artist, it’s important to suggest new ways of behaving rather than new objects.”

More emails followed: discussions about how to proceed, what the preacher might need. At this moment, a plane has been found. The next stage is to dig out an enormous, crucifix-shaped pit.

“There’s a certain amount of beauty in the ceremony of burying aircraft,” says Hiorns. “A lot of people who have witnessed it say it is unnerving. It does something emotionally to people. It feels like a death, a human burial.”

Hiorns describes himself as a puritanical artist. By which he means that he refuses to be seduced by money and fame.

He himself looks remarkably uncorrupted. In his early forties, he has peachy skin, barely a wrinkle, not a single grey in his full head of blonde hair, radiating energy and enthusiasm. There must be something in it.

Hiorns studied at Goldsmiths in the 1990s, just after the success of the Young British Artists, which he says his year reacted against.

“We weren’t going to become money artists,” he says. “We were going to instil integrity to some degree back into art. We were idealists, kind of Cromwellian, and quite happy to walk around being this.”

What this has meant is a body of work that never sinks into an easy repetition of itself. His early success was with Seizure in 2008. He filled an entire flat with copper sulphate solution, which crystallised, turning all the rooms, including a bath, a glittering deep blue, like a toxic fairies’ grotto.

A different artist could have cruised at this point, churning out variations of glittering objects to be gobbled up by a hungry art market. Not Hiorns.

In his studio, a former shop on a brutalist estate in northwest London, he turns out a cycle of work that could appear to be that of several, rather different, artists. It includes: brain matter splattered onto polystyrene wall sculptures, a jet engine stuffed with Prozac, a dense research project about Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), a church alter-piece ground to dust, and, more recently, large scale paintings of man-on-man sex.

“In my younger years, I was adamant that I would always make a body of work and then completely rip myself away from that body of work, rather like a split personality. The work was to be like a legion of people, or a kind of schizophrenia. This is what I was interested in achieving. To some degree, I still am,” he says.

He relates this drive, in part, to experiences he had during a difficult adolescence. He found himself feeling fragmented, detached from reality. “Like viewing the world through a series of holes in a piece of cardboard,” he elaborates.

How an artist might appear in their work at a personal level becomes fraught, entangled within conceptual and cultural concerns. Hiorns buries aeroplanes for many reasons: conceptually he sees it as a “double annihilation” – a destructive object, the plane, being annihilated a second time.

But the meaning changes according to where the aircraft is buried, be that Ipswich, Buenos Aires, Abuja, Prague. There can be historic references to ancient burial sites. “West Kennet Long Barrow has a similar structure to that of a buried aeroplane. You could bury an aeroplane next to it and you would have a parallel relationship, to intention and aesthetics,” he says of the neolithic tomb.

He is also deeply uneasy about flying. At times this has meant freezing at the departure gate with his passport in hand, luggage in the hold, too anxious to board. A tiny part of his unconscious might be deeply satisfied at the sight of a plane disappearing underground, never able to fly. Not that he’d ever admit it.

“It’s interesting to insult objects. I think planes are insanely beautiful things. I think what they do is incredibly beautiful. It’s just what they do to me isn’t beautiful,” he says. “Psychologically my own person history is interesting, but some people see burying planes as solely a green issue. They think I am coming at it as an environmentalist and they might see it as a provocation towards an anti-capitalist ideal. It’s a fair translation to address.”

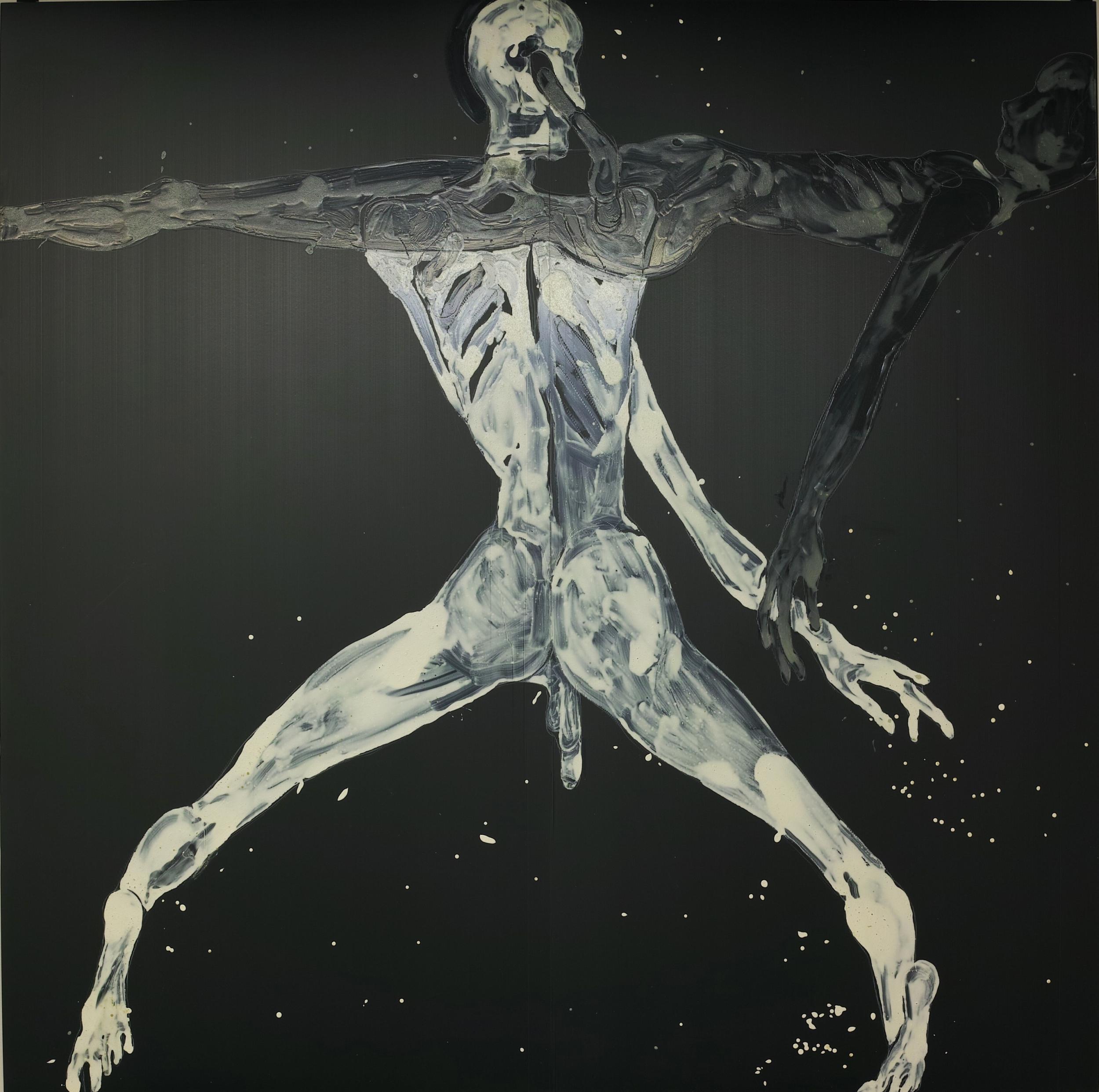

Hiorns’ latest work is a series of sex paintings in which human figures, lean and ethereal, appear in varied, often unachievable, sexual positions. Two men cross to form the shape of a crucifix, the cock of the horizontal figure in the mouth of the vertical.

To look at, they’re rather beautiful. Phantom-like figures floating in black or white space, disembodied, an absence as much as a presence. Their skin is a cocktail of latex and acrylic designed to resemble the texture of human skin. Painted onto plastic, some figures are red, others white, others brown. By representing homosexual acts, he resists objectifying the female form as well as bringing ambiguity into the work.

“Society has allowed sexuality to become ambiguous, it has allowed people to relax a bit. It’s not such a big deal,” he says. “Being gay or being sexually ambiguous even in the 1980s when I was at school was deeply problematic. We’re in the force of a pendulum swing when it comes to sexual identity. The work is not hetero-normative, it’s not looking towards a heterosexual relationship to the world, it’s looking for a queering of the world in the old fashioned sense, to make perceived problematics mainstream.

“People’s idea about sexuality is fluid and that idea of fluidity is important.”

He resists definition and directness, fully aware that the complexity in his work might assign it to the margins of the art world. That said, he hopes that his CJD project – a timeline of archival material and documentation covering the decade long crisis of mad cow disease – will one day sit next to work by Sir Anthony Caro in the Tate’s Duveen Galleries, dedicated to sculpture.

“Audience pleasing isn’t my top intention. We currently have a binary way that people seem to deal with art. If it is colourful and has a simple message then people seem to want to spend time with it,” he observes.

“I visited New York and saw Jeff Koons at the Walker Art Centre. I couldn’t believe how much art there was in the show that was just purely misogynistic, just base in terms of a shit humour. I don’t know Jeff Koons. Is his work like this because he is like this, or is he just reflecting the people who buy his work? Because a lot of people at the top end have old power and still carry a lot of these ideas. Art can carry shit ideas too. Sadly this tendency is on the increase.”

However, he notes that the only place that the avant-garde is “gestating” at the moment is in the UK, “which is actually really encouraging”.

He puts success of art in this country down to a kind of perversity. Not in a literal, sexual sense, more to do with taking something to an extreme level of belief.

“Like Stanley Spencer,” he says. “His work is deeply religious, with an exaggerated sensuality. It’s perverse. I grew up being told I was perverse by everybody. It seemed that word was used all the time. It was to do with my humour, which was challenging and antithetical to the mainstream. People welcomed it but they didn’t understand where it was coming from.”

With all that off his chest, Hiorns departs, possibly feeling a little lighter, back to the studio. “There’s a lot of work to do – it always feels like the beginning.”

Roger Hiorns is at Corvi-Mora, London, 21 June to 28 July

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments