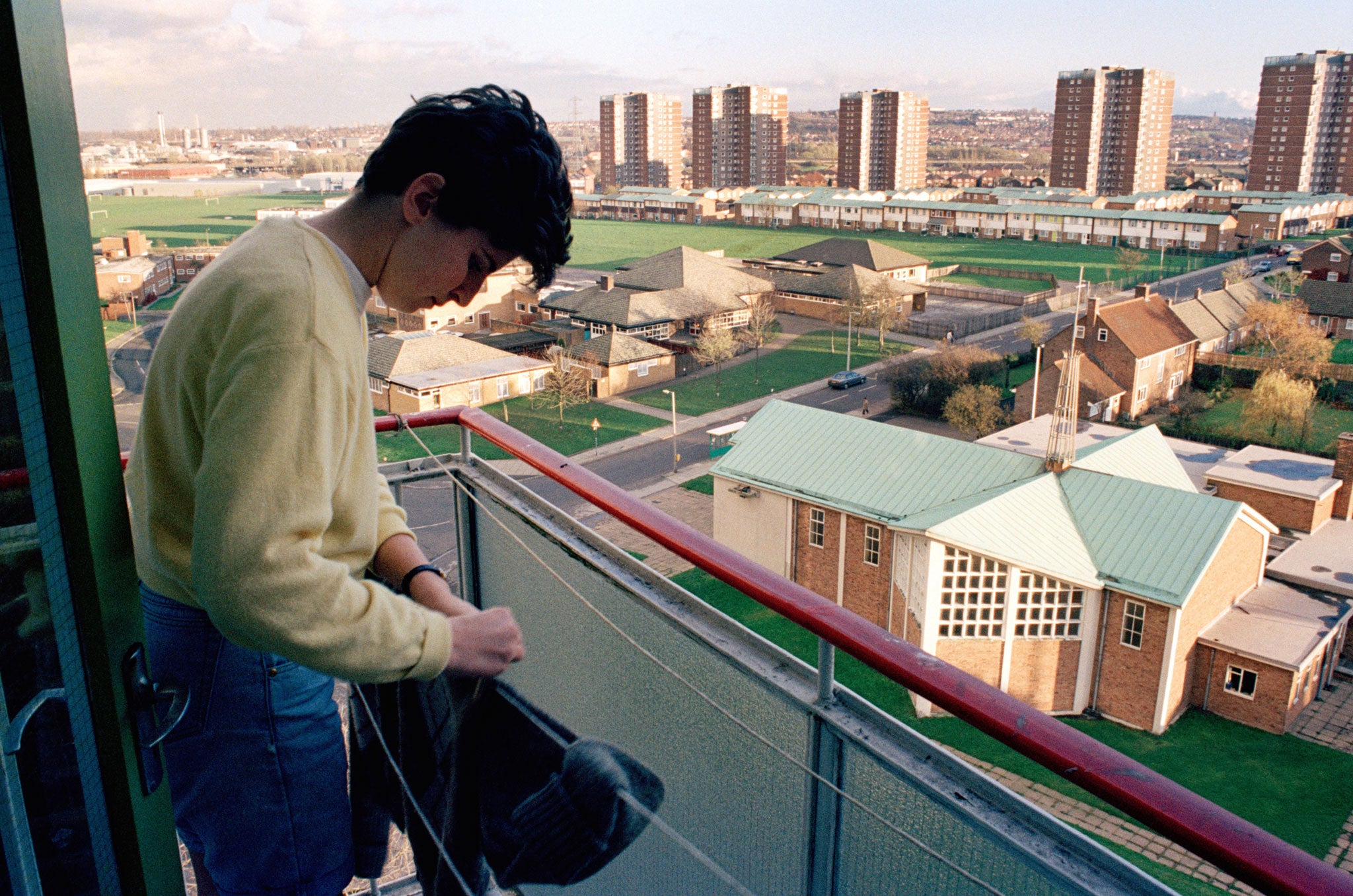

Robert Clayton's images of the Lion Farm Estate capture life in a corner of early-90s England

Jonathan Meades explores how the scenes of life in the Black Country reveal the poetry of the everyday

The Lion Farm Estate is at Oldbury in the Metropolitan Borough of Sandwell and Dudley. This is the eastern fringe of the Black Country, where it seamlessly elides with Birmingham. It is a place of former mines, former forges, ruinous factories, little-used canals and big sheds. The estate was built in the first half of the 1960s when the area was pre-post-industrial.

When Robert Clayton made his photographs of Lion Farm Estate, even its most recent buildings were more than a quarter of a century old. That was in 1991. The consensus on housing had long since ruptured. The right – right! – to buy had been introduced and with it a fiasco of unintended consequences, one of which was the establishment of a hierarchy of social housing.

What changed the complexion of social housing was the practice of "decanting" into second-tier projects, sociopaths, recidivists, junkies, the unemployable, the wilfully dependant, and the cast-out victims of another cruel wheeze of that era, the mendaciously named Care in the Community. Clayton captured Lion Farm on the eve of this calamitous invasion which would result in the partial destruction of the estate.

The strength of his vision and his work's usefulness (and poignancy) are founded in its balance. It shows a place which is worn, far from perfect, rough at the edges, where civility is perhaps provisional, where the promise of worse to come has not yet been fulfilled. Clayton resists drama and melodrama. The Black Country is among the most populous areas of Britain, yet the estate seems both far from anywhere and, more astonishingly, deserted to the point of desolation.

Clayton's reluctance to push colours is indicative of the entire project. There is no moral virtue in avoiding saturation and there is nothing "dishonest" about availing oneself of post-production tools. But there is unquestionably a documentary virtue in recording what things were like without caricature, without exaggeration, without intercession – so far as that is possible, for naturalism is, after all, a form of artifice which occludes its artifice. Still, he convinces us that this is what it was like a generation ago.

His Lion Farm was obviously not the green-and-pleasant land which the post-war consensus strove for and did, sometimes, achieve. But nor was it a dystopian slum. What Clayton recorded is valuable precisely because it shows neither a model estate, a showplace, nor a sink. The typical is elusive. It's a hard thing to capture because it surrounds us and doesn't shout. It is the 90 per cent which is habitually overlooked as we set our sights on the exceptional 10 per cent: on the one hand picture-postcard tourism, on the other frissons of delight at noxious slums.

There was nothing special about Lion Farm Estate. It could have existed in more or less any British conurbation which was on the cusp of losing its raison d'être. What is special is Clayton's humane rendering of it as a time capsule which emphasised ordinariness. This was how it was for millions of people in the early 1990s. This was Britain between Thatcherism and, well, the smiley neo-Thatcherism of New Labour. A new political consensus was in place, an insidious consensus which blithely disregarded the sort of people who lived on such estates, the invisible people, the little people who had not the wherewithal to exercise their precious right to buy. Again, Clayton leaves us to reach such conclusions. He has a broad and important socio-political point to make. It is all the more potent for being made so quietly.

This is an abridged version of an essay that accompanies Robert Clayton's book 'Estate', available at www.stayfreepublishing.co.uk. The exhibition'Estate' is at the Library of Birmingham, in conjunction with L A Noble Gallery, until 26 June

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments